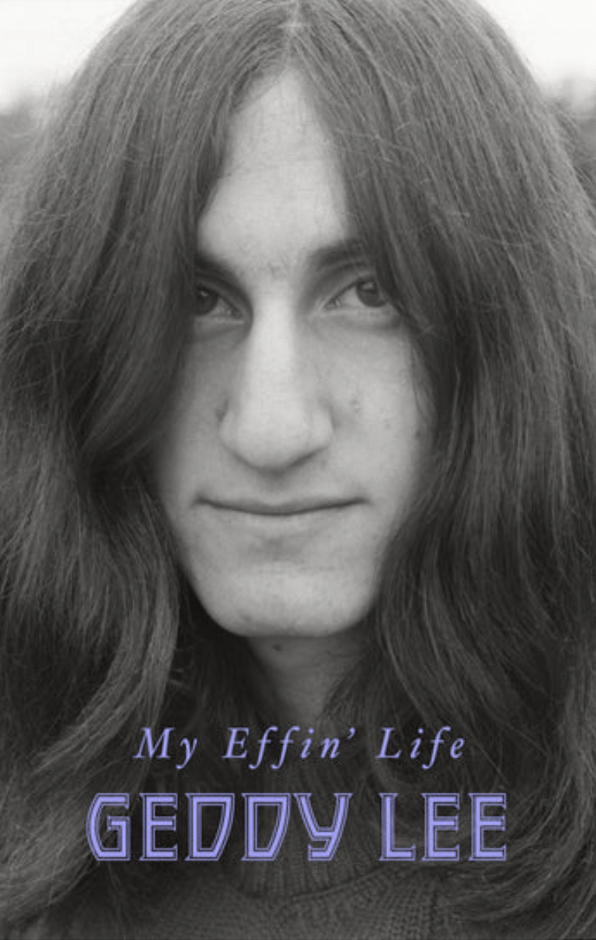

‘My Effin’ Life’: Geddy Lee’s Amazing Effin’ Read

By Geddy Lee

Harper Collins/November 2023

Reviewed by Paul Deegan

December 27, 2023

I’m not going to deliver a précis of Rush frontman Geddy Lee’s tales of sex, drugs, and rock and roll in this review. You’ll have to buy the book for that. But a quick spoiler alert: he only dishes in two of those three areas.

I’ve never met Geddy Lee. I’ve spotted him around Toronto a few times, including at a former location of Cumbrae’s butcher shop on Church Street. The store was busy, and I was the fourth or fifth person in line. Lee sauntered in – unescorted without the pretense of an entourage – and was a few people behind me in line. The butcher hollered out ‘Mr. Lee’ in a booming voice for all to hear, the Rock and Roll Hall of Famer and one of the greatest bassists of all time according to Rolling Stone, gave a nod and smiled warmly yet shyly, and simply waited his turn like everyone else.

When Lee’s long-awaited memoir hit the bookshelves, I wanted to learn more about the man behind the incredible music. Teaming up with writer Daniel Richler, Lee, who was born Gershon Eliezer Weinrib (“Geddy” was an homage to his mother’s pronunciation of “Gary”, and Lee his shortened middle name) more than delivers in this 28-chapter, 511-page tome, which, at this writing, is the No. 1 Canadian non-fiction bestseller and has spent five weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

Lee’s Canadian journey can be traced back to 1948, when his parents, Morris Weinrib and Malka “Mary” Rubinstein, both Jewish Holocaust survivors from Poland, arrived in Halifax from Germany. They had met in the Starachowice ghetto, were both imprisoned in Auschwitz, then separated — he was sent to Dachau, she to Bergen Belsen. When the war ended, Morris set out to find Malka, tracking her to the Bergen Belsen displaced persons camp. They married and came to Canada.

Lee knows little of his father’s side of the family. His dad never discussed the war. His mom, on the other hand, would talk about the horrors her family endured. Born a butcher’s daughter in Warsaw in 1925, she recalled being awakened in the middle of the night to see her father hauled away by the SS. She chased after him and held her father’s arm until the Nazis beat her unconscious and left her in the snow. Strong, fearless, and determined, she went to the train station to try to find him. When she got too close, a Nazi stabbed her with a bayonet.

Terms like “intergenerational trauma” weren’t even around when Lee was a child, but there is no question that the experiences of his parents during the Holocaust had a major impact on Lee’s life – bringing him both deep pain and the zeal to lead a life well-lived.

As a child, Lee saw himself as a nerdy loner. He was gawky and self-conscious, and he endured the pain of losing his father at the age of 12. After observing the formal Jewish rules for grieving, which included no music allowed at home, Lee was encouraged by his mom to move forward with his teenage life.

Rush fans owe a debt of gratitude to Terry Kurtzer, Lee’s next-door neighbour, who sold him an acoustic guitar. A few kids in the neighborhood got together and formed a band. Lee played acoustic until their bassist’s mother forbade her son from hanging out with Lee and his fellow degenerates. His bass was sold to Lee, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Lee describes his childhood friend Alex Lifeson as a teacher’s pet who sat in the front row. Soon, the pair were goofing off in the back row talking music. Alex has a friend named John Rutsey. The two were in a band that Rutsey’s older brother suggested they rename ‘Rush’.

When Lee would play in his basement with guitarist Lifeson and drummer Rutsey, his grandmother, who had also survived the death camps, would yell epithets at the future rockstars in Polish and bang pots and pans in protest.

Lee captures the texture and spirit of a Canadian adolescence spent in the suburban tension between daily assimilation and epic legacy, between the ever-present past of that generation of Jewish refugees from Hell — the Pier 21 arrivals who’d made it out alive — and the promise of a free future of endless possibility.

Lee liked singing and wasn’t shy about it – who knows; maybe it was practising his Torah portion for his Bar Mitzvah that gave him the confidence. Lee writes that he was never aiming for raspiness in his singing: “If the key we wrote a song in felt right, I’d just have to make do. What we came to learn was that in certain lower register, my voice had no power, but when I booted it up an octave, there was the power!”

Connecting back to his childhood, Lee writes, “My earliest vocal style may also have been rooted in my childhood, listening to the stories of what my parents had endured in the camps, suffering all that bullying and alienation, so that when I did begin to sing it did come rushing out as a screaming banshee. I was releasing all those supressed emotions just stepping up to the mic and screaming Ooh yeah! Of course, then I had to learn how to actually sing…”

In that sense, Lee’s book is about much more than the classic rock-memoir fare about life on the road and a consuming love affair with music. It is also about the quintessential Canadian (and American) story of growing up with post-war immigrant parents. More precisely, Lee captures the texture and spirit of a Canadian adolescence spent in the suburban tension between daily assimilation and epic legacy, between the ever-present past of that generation of Jewish refugees from Hell — the Pier 21 arrivals who’d made it out alive — and the promise of a free future of endless possibility. That Lee grew up to be an inductee into both the Order of Canada and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame more than delivered on that promise. It also truly makes you wish Morris Weinrib had lived to see it.

A key moment in the author’s formative suburban Toronto life came when the teenage Lee met the girl he today describes as a ‘beautiful, sexy redhead’, but first and foremost “Smart as a whip with intuitive superpowers!” In Nancy Young, he found some of the same traits his mom had – strong, with an innate sense of right and wrong and a deep well of kindness. Nancy being a gentile was never an issue for Lee, who had left religion after his dad died, but it wasn’t something his mom had envisioned for her son. Nancy did convert – not under any pressure – but because she knew what Lee’s mom endured during the Holocaust and wanted her to know that she respected her faith. Lee compares the great quantities of food on his mother’s table to the first time he had dinner at Nancys’ parents’ home where everything was plated and apportioned, and it reminded me of my wife’s (who is Jewish) reaction to having dinner at my mom and dad’s.

Lee’s writes his mom’s dementia was a ‘painful reminder of how fragile our memory banks are’. This is what inspired him to jot down his life’s story – a story that he clearly needed to get out: “Walking gingerly across a minefield of difficulties, scraping away to reveal some kind of truth, has been all-consuming, exhausting and at times distressing, but now that I’m nearing the end, I can already feel a weight lift off my shoulders. I feel like I can breathe fresh air through these cavernous nostrils for the first time in ages.”

One leaves the book with the feeling that Lee has more to do and more to say. Let’s hope he writes about his second act in a few years.

In short, it’s an effin’ amazing read.

Paul Deegan is a contributing writer to Policy Magazine