Neither Rain, Nor Snow, Nor CPI…

By Douglas Porter

February 16, 2024

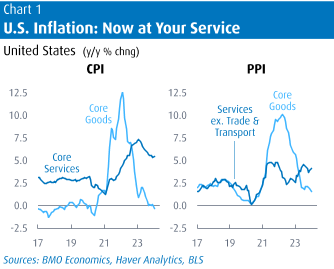

…shall keep the index from its appointed records. But perhaps PPI can. Ebullient equity markets contended with a series of challenging U.S. economic releases this week, including hotter-than-expected CPI and PPI readings, and surprising weakness in each of retail sales, industrial production and housing starts (all five for January). Even so, the S&P 500 had still managed to reclaim a new high by Thursday’s close, as had the MSCI World Index—which, admittedly, is not far from being a U.S. index these days. Brushing aside a short-lived downdraft following the CPI release, markets revved back up on a healthy earnings backdrop and were even enthused by the softness in retail sales, viewing it as keeping Fed rate cut hopes alive. Treasuries, too, had largely managed to shake off the post-CPI sell-off, in part due to a sudden run of soft growth indicators and reassuring Fedspeak.

However, the surprisingly meaty PPI revived lingering concerns that the CPI upturn was more than a seasonal spike. The report revealed a 0.8% rise in services excluding trade & transportation, the second largest monthly rise in over 14 years of records. While never a big fan of the PPI—what does it really add to the CPI result?—it’s not a good look for an economy already grappling with sticky services inflation. The sting of the CPI had been partially dulled by the fact that the Fed targets the PCE deflator, and that measure has been much milder of late. But the hefty PPI raised the risk that even the January PCE will come in hot (due Feb. 29). Even if that’s so, the real test will be whether the hearty inflation results spill over into February—then, we have a problem. Our assumption is that many firms are seizing on the calendar turn to hike prices, and January likely represents an outlier, not the start of a trend.

Still, Treasuries were further unsettled on net this week by the twin price reports, with 10-year yields pushing above 4.3% for the first time since November, and up more than 50 bps from the late-2023 lows. In just the two weeks since the payrolls report, these yields have jumped more than 40 bps. It’s been a bearish flattening move since then, with 2s up 45 bps and 5s surging almost 50 bps. Markets are steadily pushing Fed rate cuts later into the calendar, with now even the June meeting in some doubt. Back-to-back high-end price readings are not the stuff that will give the Fed confidence that inflation is on the right track. Suffice it to say that we are comfortable with our call of a July start. But pricing has shifted so markedly that our expectation of 100 bps of cumulative rate reductions this year is now a bit more than the market expects, so we have abruptly swung from being relative hawks to doves, without changing our view.

Canadian markets have had a broadly similar rethink, with GoC yields powering up by about 50 bps nearly across the curve as well from last December’s lows. The local CPI will weigh in next Tuesday, and we expect it to be heavy. In seasonally adjusted terms, we look for at least a 0.3% rise, keeping the annual inflation rate at 3.4% (versus the U.S.drop to 3.1%). And, the BoC’s cores are expected to nudge higher, not lower. In contrast to some encouraging remarks by a variety of Fed speakers, the Bank has stuck to a tougher message, even as the Canadian economy is struggling more obviously with the higher interest rate environment. The reality is that with wages still chugging along at a 5% clip and productivity flailing, the Bank will have little confidence that services inflation will fade on its own.

Rumbling away in the background, housing is an ever-present source of concern for the Canadian inflation outlook. Having devoted much of his recent speech to the topic of persistent shelter inflation, Governor Macklem will have noted the signs of stirring in home sales in the past two months. The market has retightened to be roughly balanced in many cities, and the widespread consensus is that, amid pent-up demand and powerful demographic support, rate cuts could unleash activity. (Aside: Note that supply is categorically not riding to the rescue anytime soon. Starts have in fact ebbed to 240,000 units over the past year, versus 260,000 in the prior 12 months. Based on the current torrid growth in the adult population, the need is for at least 500,000 new units per year—stress on “at least”.) This coiled spring may be itself a strong reason to believe that the Bank will be exceptionally cautious in cutting rates.

Similar to pricing for the Fed, the market has steadily dialed back its views on BoC rate cuts in 2024. Our call of a June start now looks a tad dovish, although the market still has that meeting on the radar. But our cumulative cuts of 100 bps this year look positively perky versus a more subdued market expectation of 50-to-75 bps. There is still plenty of data to flow under the bridge, but it does appear that the risks lie to the low side of our call for cuts this year, with employment hanging in, housing showing a pulse and core inflation sticky.

Finally, while the Canadian economy is struggling to grow, it’s not obviously rolling over; construction, manufacturing and wholesale trade were all close to flat in volume terms in December, suggesting that GDP is still just holding its head above water. The most recent consensus survey (conducted just this week) revealed a small pick-up in growth expectations for 2024, albeit to a very modest 0.6% (we and the BoC are at 0.8%). While that’s paltry stacked up against 3%+ population growth, at least it’s still positive.

Best. Recession. Ever. Japan’s GDP did not manage to stay positive in the second half of last year, prompting a flood of headlines declaring the world’s fourth largest economy to be “in recession”. Yet, this is a classic example of how two quarters of negative GDP do not necessarily equal recession. (And for the umpteenth time, it is a rough guideline only.) First, Japan’s data are especially prone to revision, and are quite volatile. The ‘recession’ could easily be revised away. Second, even with the second-half sag, GDP was still up 1.1% y/y in Q4. In a nation where population is down 0.5% y/y, that’s not a bad performance at all. Third, Japan’s jobless rate has actually dropped a tick over the past year to just 2.4%, not quite what one would expect in a true recession. And, finally, if Japan was in a recession, someone forgot to tell the Nikkei, which is busily approaching a record high (finally poised to eclipse the end-1989 apex) and up an astonishing 15% this year alone. We should all wish for such a dire economic backdrop.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.