October Classic

Doug Porter

October 28, 2022

The Bank of Canada had its 15 minutes of global fame on Wednesday, when its somewhat surprisingly light 50 bp rate hike fired up expectations of a broader shift among central banks. While the initial euphoria soon faded, financial markets still enjoyed another solid week and are headed for a strong October comeback. Even with a rocky ride for many of the mega-cap tech stocks, the broader indices are on track for a robust month—to wit, the Dow is currently on pace for a 13% surge in October, the best monthly gain since 1987. (We are far too polite to mention that discussing stocks and 1987 in the same sentence is typically not a positive comparison.)

While stocks were gamely reversing some of their September losses, the biggest rally this week was in Canadian bonds. To pick just one key yield, the 5-year GoC was flirting with the 3.9% level just one short week ago, the highest in 15 years. A rapid-fire series of events has massively turned the tide, led first by some mildly dovish comments by Fed officials late last week, a calmer backdrop in the U.K., and of course the aforementioned BoC surprise step.

Certainly, a big drop in Treasury yields paved the way; U.S. 10s were down a hefty 21 bps from last Friday’s close to back around 4%. But Canadas went a step further, with 2s down 32 bps on the week, 5s down a massive 34 bps, and 10s down a whopping 36 bps. The rally took 10-year GoC yields to nearly 3.2%, or 76 bps below like-dated U.S. levels, the widest gap since pre-pandemic days in 2019 and not far from record wide levels. Note that little more than three months ago, Canadian 10-year bond yields were slightly above their U.S. counterparts; now, they are flirting with record negative spreads. The big shift has been in part driven by the view that the BoC will ultimately hike by less than the Fed, a view that was reinforced—big-time—by this week’s BoC decision.

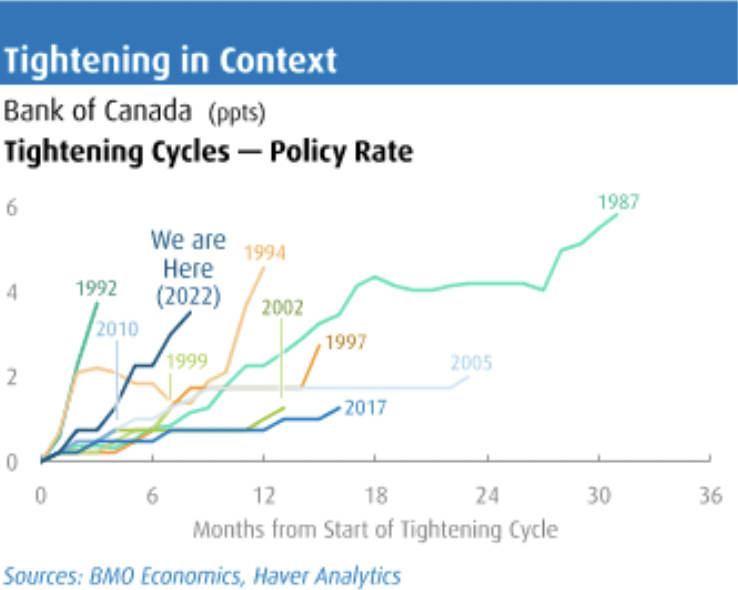

Some suggested that the BoC has “blinked” in the face of external pressure and/or on signs that growth is stalling. Oh, please. First, as a reminder, a 50 bp hike is still an aggressive step—prior to this year, no major central bank in the world had hiked by as much as 50 bps in a single step in the past 20 years. Second, the BoC now has the highest policy rate in the G10 at 3.75%, and has hiked by more than any of the group so far this year at 350 bps. Third, as the accompanying chart (courtesy of Robert Kavcic) amply displays, this is still one of the most aggressive and rapid hiking cycles by the Bank on record. In other words, it was inevitable that the Bank was going to eventually slow the rapid-fire pace of rate hikes, and it’s far too soon to be calling for an end to hikes.

True, we had thought that the Bank’s self-declared front-loading bias pointed to a bigger 75 bp step this week, but we don’t believe that the end-point has changed. We had expected the Bank to hike one more time to end at 4.25%, and we are maintaining that terminal rate, with 25 bp hikes now pencilled in for the next two meetings. If the next CPI lands on the high side, and/or energy and food costs keep climbing, the Bank could easily opt for another 50 bp hike in early December. Either way, it is reasonably clear now that the Bank will do a bit less than the Fed, with the latter still fully expected to hike 75 bps next week, then step down to 50 bp and 25 bp hikes in the two following meetings. That would take Fed funds to 4.50%-to-4.75%, versus a 4.25% overnight rate in Canada.

That slightly different outlook reflects somewhat more intense inflation and wage pressures in the U.S., as well as a more indebted, and thus more vulnerable, Canadian consumer. Notably, even with the BoC’s small surprise, the Canadian dollar barely blinked on balance this week. In fact, the currency firmed slightly to around 73.5 cents (or right around the $1.36/US$ level), after pushing below 72 cents just two weeks ago. The U.S. dollar itself looks to be losing a bit of steam, with heavy-duty intervention by the BoJ and less U.K. drama helping revive the yen and the pound, respectively.

Some newfound stability in the loonie will provide the BoC with a bit more room to manoeuvre, as the previous deep slide had threatened to aggravate inflation. As it stands, Canada still boasts one of the lowest inflation rates in the advanced world at just under 7% (apart from Japan’s 3% rate, of course). Australia’s latest quarterly figures suddenly drove them above Canada to 7.3%, while the U.S. CPI remains stuck above 8%, and Britain has pushed above 10%. Meantime, early estimates for October point to a big step up in Europe, with France at the low end at just above 7%, Germany popping to well above 11% and Italy spiking to nearly a 13% pace this month. The bottom line is that the Bank of Canada has moved the furthest and fastest on interest rates, while Canada has among the mildest inflation trends—so it’s far from a dovish signal to step down to a 50 bp hike.

Perhaps one source of potential support for the Canadian dollar in the months and years ahead is a generally stronger fiscal position than most other major economies. In recent weeks, we have seen a steady string of provinces report much better-than-expected outcomes for FY21/22, with no fewer than six revealing surpluses for last year (including the biggest four). Adding to the mix, the federal government announced on Thursday that its deficit for last fiscal year (ending in March/22) plunged to $90 billion, compared with the budget estimate of $113.8 billion, and little more than one quarter of the pandemic blowout of $327.7 billion in FY20/21. Yes, that is still the second largest shortfall on record, but at a bit below 4% of GDP, it has moved back into the manageable zone and is still falling fast. In the first five months of this fiscal year, Ottawa ran a small surplus of $3.9 billion, on course to do far better than the projected $53 billion deficit for the full year. Still, the rapid rise in borrowing costs and our call of no GDP growth next year will dent finances heavily, but it appears that the much better starting point for revenues will leave deficit projections beyond this year mostly intact.

Finance Minister Freeland will unveil the Fall Fiscal Statement on November 3, in the midst of an absolutely jam-packed week of economic events and news. The Statement will be wedged between the FOMC on Wednesday, and the twin October job reports on Friday. The key to watch from Ottawa is whether, and to what extent, the federal government attempts to soften the blow for Canadians from 40-year high inflation. Nationally, total fiscal steps to-date, including a variety of provinces doling out cheques, have pushed above $11 billion, or a moderate 0.4% of GDP. The Minister has often pointed out that Ottawa simply cannot lighten the load for everyone, and has clearly heard the message (loudly delivered from London) that fiscal policy should not act at cross purposes to monetary policy. As such, we would expect a relatively quiet affair next week, without any large-scale new measures.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.