‘One Phone Call’: Who’ll Stop Myanmar’s Democide?

If Beijing were inclined to rein in the generals, #WhatsHappeninginMyanmar wouldn’t be happening.

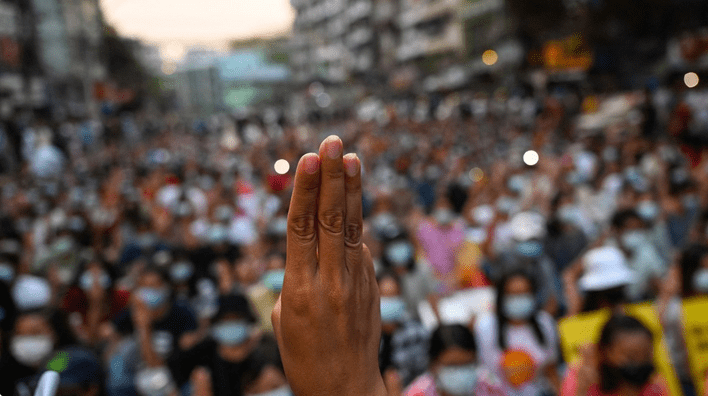

A protester makes the three-finger pro-democracy salute in Yangon, March 13, 2021/AFP

Lisa Van Dusen

April 8, 2021

In an interview with CNN’s Becky Anderson on Wednesday, Salai Maung Taing San (known as Dr. Sasa), the United Nations special envoy of the democratically elected, violently deposed government of Myanmar, responded to the crucial question of what neighbouring China and its anti-democracy sidekick, Russia, could do to stop the rampage of post-coup terrorism being waged by his country’s military against its own people.

“Russia and China can make just one phone call to the military generals,” Dr. Sasa responded. “One phone call can stop the military generals.”

In a previous era, that might have sounded naïve. At a moment when China’s globalized anti-democracy tactics are evident in so much of what the Tatmadaw is inflicting on the Burmese people — from the daily viral acts of brutality seemingly curated for maximum terror to the ludicrously misdirectional Orwellian rhetoric to the fact that the junta felt sufficiently secure about Beijing’s amenability in the first place to stage a coup against a government elected in a landslide in November — it’s an entirely logical assumption.

If Beijing were not supporting the Tatmadaw’s tactics, it would not be blocking meaningful action against the Myanmar military at the UN Security Council, it would not be warning against “foreign interference” in Myanmar’s violence, it would not have wryly dubbed the coup a “major cabinet reshuffle”, and it would be advocating the release from detention of State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, followed by the swearing-in of the country’s legitimate government. Instead, the people of Myanmar continue to protest amid internet blackouts, hunting by snipers, detentions and torture.

In his Wednesday briefing this week, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres deplored the ongoing use of an anti-humanitarian tactic taken to new lows in Syria and resurfacing in Myanmar, the targeting of medical personnel and ambulances. In her own piece from Myanmar on Wednesday, CNN’s Clarissa Ward pointed out the preposterousness of the junta’s pledge to hold new elections when they haven’t respected the results — deemed free and fair by international observers — of the election that provoked the coup. Responding to Ward’s airing of a video of soldiers shooting a 17-year-old in cold blood in a killing officially described as a bicycle accident, Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun promised an investigation. “We will investigate whether the video is real or not,” said the chief of the “Tatmadaw True News Information Team” (seriously).

That contempt for truth is more than just another example of the classic first casualty of war. In the current global conflict between democracy and totalitarianism identified as a major challenge by President Joe Biden, multiple narratives — from China’s default belligerence to every hour of every day of Donald Trump’s presidency to the Republican Party’s ongoing, organized attack on voting rights — have been propelled by absolutely outlandish deception. The Myanmar narrative, which would swing back toward democracy with Aung San Suu Kyi’s release and the previously scheduled programming of the swearing-in of the government, has been overtaken by horror rationalized by a fog of lies, including the fabricated charges against the country’s legitimate leader.

This week’s post-coup coup de grâce was the arrest of the country’s most popular comedian, Zarganar — a move reflecting a global anti-democracy obsession with silencing criticism so granular it makes analog totalitarianism look thick-skinned.

“They’ve condemned the violence, but not the coup,” UN Special Rapporteur on Myanmar Tom Andrews told CBC’s Matt Galloway on March 31 of his own organization’s Security Council. “I mean, this is a reign of terror going on here [in Myanmar],” he said. “We have these marauding troops now going through neighbourhoods, destroying property and then shooting randomly into people’s homes.” This week’s post-coup coup de grâce was the arrest of the country’s most popular comedian, Zarganar — a move reflecting a global anti-democracy obsession with silencing criticism so granular it makes analog totalitarianism look thick-skinned. That was followed by the arrest of the country’s best-known male model and other democracy-supporting celebrities, just in case there was any misunderstanding about the junta’s clickbait abduction criteria.

We’ve all revisited the definition of genocide recently following the Rohingya genocide in Myanmar and amid the Uyghur Xinjiang genocide being waged by China. But what’s happening in Myanmar now is what US political scientist Rudolph Rummel termed “democide” — “the intentional killing of unarmed or disarmed people by government agents acting in their authoritative capacity and pursuant to government policy or high command.” Rummel’s democratic peace theory pointed out that democracy is the form of government least likely to kill its own citizens.

Canada, the US, the UK, the EU and other countries have imposed sanctions on Myanmar’s military, and we know those are effective based on the usual vested-interest commentary saying they’re not. But the UNSC’s response has been limited by Russia and China’s vetoes as permanent members of the 15-member body and in larger, systemic terms by the broader influence China now wields at UN organizations. At the same time, Beijing prefers to triangulate such crises to regional bodies like ASEAN, underscoring both its ironic aversion to multilateral “interference” from groups that include the US and other western democracies and reinforcing the weakness of the global conflict resolution organization of record it has spent so many years corruption-capturing.

Over the past decade, China’s expanding influence as the geopolitical tentpole of the anti-democracy trend has never been wielded to strengthen democracy. It has been wielded exclusively — in economic, diplomatic, trade, cyber, and all other terms possible — to weaken democracy, directly or indirectly, immediately or long term.

One phone call to the generals in Naypyitaw telling them to stop the slaughter and respect the will of the people would be the right thing to do on every rational level. But since this amounts to a narrative proxy war against Myanmar democracy, it would also represent a conflict of interest, as well as a stunning deviation from China’s 21st century record on power consolidation vs. human rights.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor and deputy publisher of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.