‘Our America’: An Epic Told in Moments

Our America: A Photographic History

By Ken Burns

Penguin Random House/ November 2022

Reviewed by

Anthony Wilson-Smith

In an era in which people rely so much on visual and digital tools for information, there is arguably no chronicler of American history more important than Ken Burns. For close to five decades, the Walpole, New Hampshire-based documentary-filmmaker has examined past life in the United States in lengthy, deeply researched films that have earned significant acclaim, and audiences.

Burns’s documentaries, which take years to produce, combine grainy old film sequences, letters, other documents, first-person testimonies, period photographs and anything else that brings life and immediacy to his subjects. His topics range from baseball to the Civil War to race relations to jazz to, most recently, what the United States did and didn’t do in response to the Holocaust before and during the Second World War.

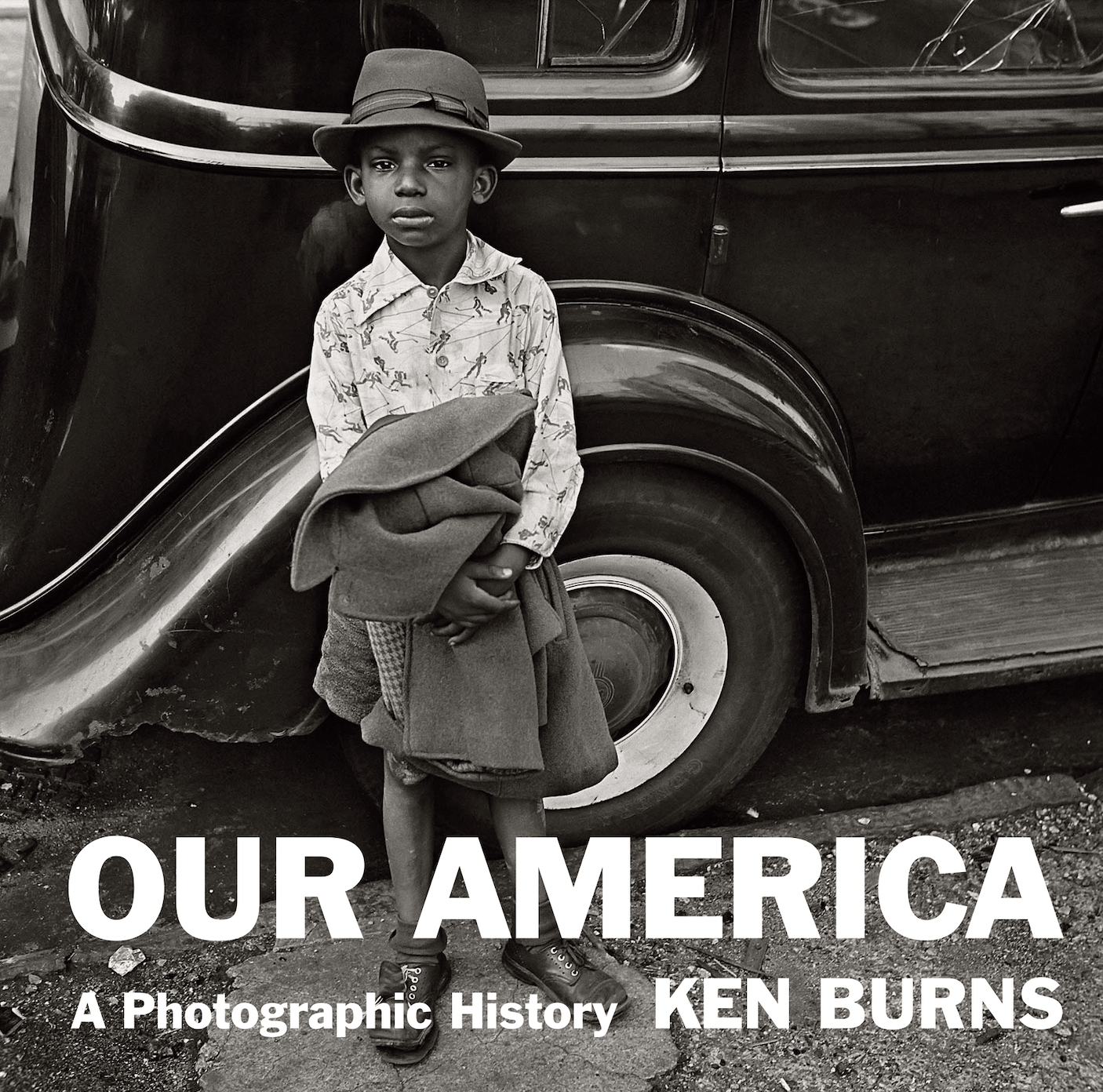

Which makes it somewhat surprising that Burns chose a book as format for his newest, most sweeping project. Our America: A Photographic History is as large as its subject: at a thumping 4.8 pounds, it challenges the load capacity of any coffee table supporting it. The book’s goal, Burns writes, is to acknowledge “the history of the US but also the history of ‘us’, the two-letter, lower case plural pronoun that in its intimacy often balances out the majesty, the complexity, the contradictions and the controversy of its larger counterpart.”

Working with three co-authors from his Florentine Films production company, Burns provides 245 full-page images, starting in 1839 and ending in 2019. The black-and-white photographs touch on almost every aspect imaginable around the American dream – and its concurrent nightmares. Those are matched by summaries of the circumstances of each at the end of the book, deliberately separated from the related images.

That is one of the ways that Burns challenges those who follow his work. As with his documentaries, his material sometimes jumps from one subject to another in a manner that can initially seem fragmented and unrelated in context. But that is precisely the point: while historical events are often portrayed in the re-telling in a tidy, linear fashion with a convenient beginning, middle and end, living through them is far more chaotic, and not everyone experienced the outcome the same way, or rejoiced in it. A single-focus narrative misses the point that what is left out of a story can matter every bit as much as what is included.

As this book demonstrates so vividly, countries flourish when they focus on the qualities that unite more than those that divide, and fail when they do not.

The reliance on still photographs represents, for Burns, a return to the form that, for him, has always been the most compelling. He was first smitten at age three when his father took him into the makeshift darkroom of their Delaware home to develop photographs. That passion grew as he grew older. Today, he writes, “I don’t just look at [a] photograph and imagine the compositional possibilities. I listen to it, as well. Are the troops trampling, the cannons firing, the leaves rustling?” And, by extension, does the photograph contribute to a larger tale of how life was in a different time – and how that has shaped the world in which we now live?

Burns understands the enormous power of images both to inform and, on occasion, to deceive. He reminds us how dangerously misleading a little knowledge can be. A 1941 photograph of a standing-room-only gathering at New York’s Madison Square Garden, festooned with stars-and-stripes flags, may seem a massive gesture of support during the Second World War. In fact, taken before the United States entered the conflict, it is a pro-isolationist rally with Nazi undertones and swastikas also waving.

In other photographs, the image is what it seems, but with a deeper backstory. An 1863 photo of “Gordon”, a Black former slave, shows his back covered in scars from repeated lashings. Gordon went on to be a soldier, fighting for the Union side alongside other former slaves. In a similar vein, there are First World War pictures of Black and Choctaw (Indigenous) soldiers in uniform, marching off to fight for their country despite the many legalized forms of discrimination practiced against them.

The March on Washington by James K. Atherton/Library of Congress

The March on Washington by James K. Atherton/Library of Congress

At the same time, Burns shows the beauty in his country’s many achievements – such as a breathtaking photo of Orville Wright’s plane floating over Kitty Hawk in his history-making flight. Other photos evoke the sometimes baffling emotions undergone in a country that once went to war against itself: a 1913 photo of Confederate and Union veterans meeting 50 years after the Battle of Gettysburg shows the now-elderly men embracing like brothers half a century after their younger selves tried to kill each other.

For Americans – and for Canadians as their neighbours – the photos are a reminder that the fault lines we see today have always existed, and have not always been transcended. That is true of any nation — including Canada — but it looms larger as a reality in a country as culturally, economically and geopolitically important as the United States. “I take exception,” Burns writes, “to an automatic assumption of American exceptionalism, but we do find much that is exceptional in these images…amid the dark and perilous divisions that threaten still to overtake us.”

As this book demonstrates so vividly, countries flourish when they focus on the qualities that unite more than those that divide, and fail when they do not. That is always easier to say than to achieve.

Contributing Writer Anthony Wilson-Smith, President and CEO of Historica Canada, is a former editor-in-chief of Maclean’s.