Party Members Don’t Pick Leaders, and They Should

Leadership conventions in Canada were once a climactic, integral part of a political party’s cyclical renewal and political zeitgeist footprint. They were sometimes bloodbaths and often left wounds that lasted a generation. The systems that replaced them have lessened the risks of internecine warfare but increased those of outsider hacking and the disenfranchisement of loyal supporters and elected representatives. Former New Democratic Party president Brian Topp has some solutions.

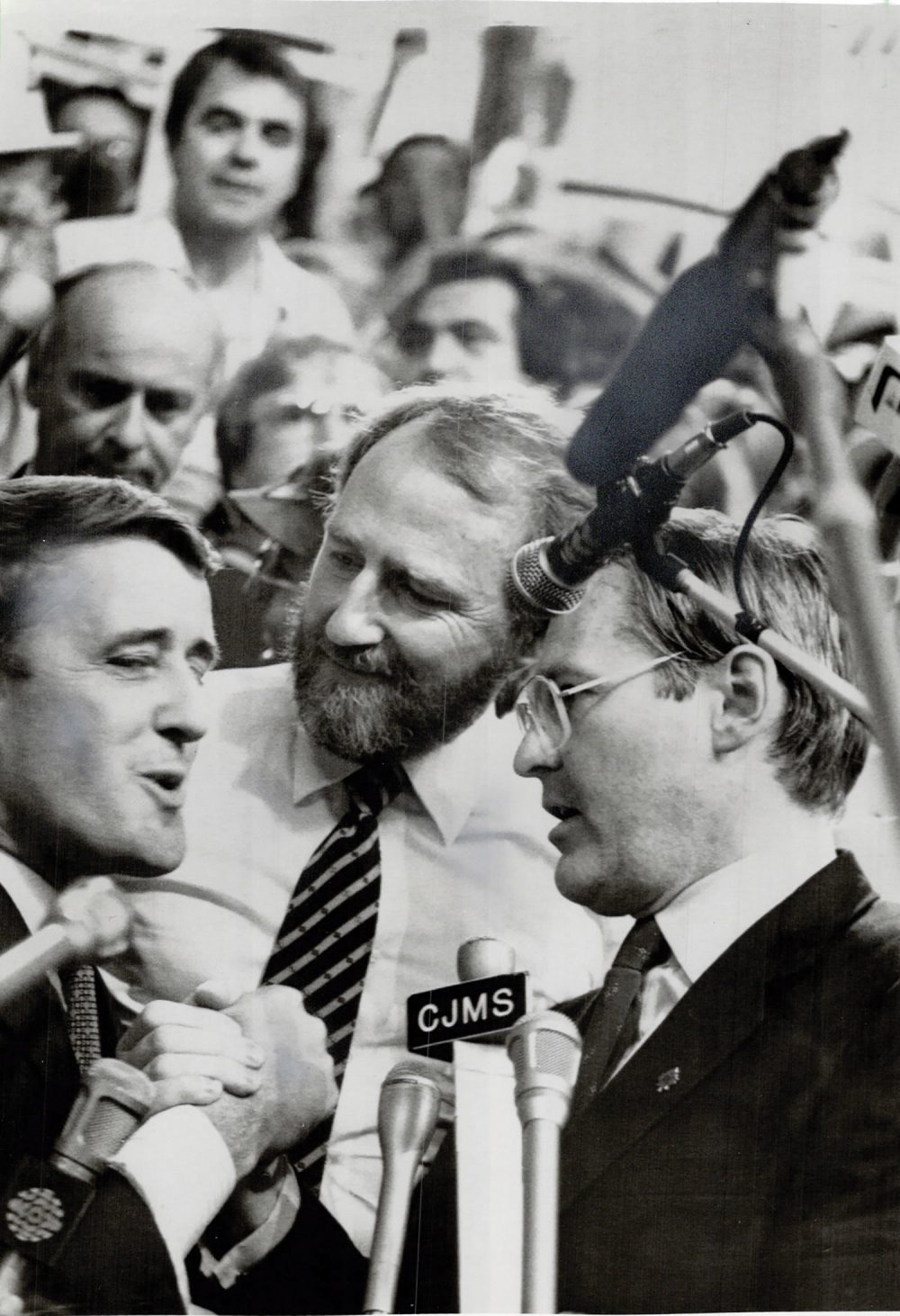

Brian Topp

As I write, the Democratic caucuses in Iowa have just disintegrated into farce. And all across Canada, Canadians were no doubt thanking their lucky stars that our country does not labour under the dysfunctional mess-by-design that is U.S. presidential politics. But as on many other files, we should not be too smug. The Conservative Party of Canada’s 2020 leadership race reminds us that our major political parties all struggle with leadership selection systems that also, in their own ways, disempower their party members and their elected parliamentary caucuses.

We can, I submit, do better.

First, let’s discuss how we got here, and what I mean when I say that all our current systems disempower their members and elected representatives.

For the first century or so of Canada’s history of responsible government, leadership elections were straightforward matters. MPs picked leaders from their own ranks. In light of what has followed, we might wonder whether it was wise to abandon this model. The revolving door of recent Australian leadership arguably reassures us that Canadians made the right call in abandoning caucus leadership selection.

As the regular defenestration of Australian leaders—even when they’ve recently won general elections—demonstrates, parties aren’t governed well by leadership systems that are exclusively in the control of elected MPs. Senior front bench MPs want to be leader. If they are operating in a system in which they can simply plot among fellow MPs to replace the incumbent with themselves, they will. We probably don’t need that kind of permanent instability here.

In 1919, the Liberals inaugurated leadership selection by delegated convention, electing Mackenzie King that way. Other parties soon copied this model. There is much to be said for this system. First, it was fun, providing several generations of Canadians with exciting political spectacles, such as the 1968 Liberal Trudeau convention and the 1983 Conservative Mulroney one. More important, as long as the delegates participating in these conventions were really “delegates”—i.e., well-respected local party members who had been elected by their fellow members to represent their views and then to use their best judgment—then those conventions were examples of party democracy working well.

Aleadership convention could become a true deliberative assembly, in which the party’s most engaged activists met to collectively discuss what kind of party they wanted to be and whom they wanted to incarnate it. We have seen this at work quite recently. The Ontario Liberal Party changed its mind after hearing out the candidates, set aside front-runner Sandra Pupatello, and named Kathleen Wynne as leader and premier of Ontario in 2013 because she impressed them more and spoke to their values better. However, delegated conventions in all parties drifted far away from this.

This occurred because well-funded and professionally-led leadership campaign teams reached around local party democracy and flooded the delegate-selection process with instant “members” and slates of candidates for delegate spots. Instead of a deliberative process, delegated conventions became local organizing and fundraising tests—still exciting and fun, but destructive to the value of membership. Caucuses of MPs, meanwhile, became essentially irrelevant to the process—and were then handed a leader they might or might not wish to work with. One-member-one-vote voting systems—widely adopted by Canadian political parties in the 1990s and 2000s—were supposed to cure these problems. Members would be re-empowered by being given a direct vote.

This has not turned out to be the case under the model adopted by most Conservative parties, which weighs votes by riding. The idea here is that each riding is worth 100 points, and the members in that riding vote their 100 points—giving candidates a strong incentive, it is argued, to campaign across the country. What it actually does is give candidates a strong incentive to organize ridings where the party is weakest, since very small numbers of members have the same weight in this system as ridings with thousands of members. Medicine Hat might have 5,000 Tory members. Argenteuil might have, say, 25 members who happen to be regulated milk farmers and social conservative issue-voters. Both ridings are worth the same number of leadership votes in the CPC race.

Organizing weak ridings is how Christy Clark became leader of the B.C. Liberals, and how Doug Ford became leader of the Ontario Conservatives. You could aim a utilitarian argument at this—Clark and Ford played smart, and both then went on to win their elections. But party members and caucuses aren’t at the heart of this system and that is, I submit, ultimately destructive to political parties.

Members also weren’t re-empowered by the pure one-member-one-vote system widely adopted in the NDP. The merit of a pure one-member-one-vote system is that every member’s vote is equal and equally valued. But as practised in the NDP, this model has simply reimported the worst problems of traditional delegate selection elections into one big vote. The ballot is wide-open to instant members, recruited—for one minute, while they vote—from outside of the party. That is, for example, how Ujjal Dosanjh won the leadership of the B.C. NDP, so that he could then preside over the annihilation of that party’s caucus before becoming a Liberal.

The benefit of this system was supposed to be that instant members recruited for one minute in order to vote would stay, become full members, and thus grow the party’s membership and fundraising base. But there is no evidence that this ever occurs. They don’t stay, generally speaking, and they don’t become contributors. So, the bargain—disempowering party members and the parliamentary caucus in return for growing the list of members and its financial resources—has failed and will probably continue to do so.

So, what’s the solution?

First, I suggest that leadership candidates should require nominations from elected federal MPs or provincial MLAs. That’s how the British Labour Party does it (the U.K. Tories go a little further and use their caucus to narrow the ballot down to two finalists). In the result, what elected people think would matter again. The process of obtaining their support would provide some free publicity for leadership candidates, while putting elected caucuses at the heart of the leadership process. More of the time than currently, no-hope and distraction candidates would be screened out. And more of the time than currently, so would individuals known by their colleagues to have dysfunctional personalities or issues of conduct that make them poor candidates for leader, even if they speak well on television.

In federalized Canada, and in a first-past-the-post electoral system that often elects very modest numbers of federal NDP MPs with large gaps in its regional representation, I suggest that endorsements from 20 MPs or provincial MLAs be required. Arguably, you could go a step further, in the NDP, and add federal council members to this list of potential nominators. The Canadian Tories are currently trying to get to the same outcome with a $300,000 entry fee. But Canadian political parties should get money and brute-force organizing out of leadership races. Let the elected caucuses do the initial political vetting with their best judgment, instead of leaving it to party bagpersons.

Secondly, to vote, members should have been a full member in good standing for at least 12 months—no exceptions. So, leadership races would not be about creating soap bubble membership lists at a party office. And they would not be about recruiting donors who in reality will never donate again. And they would not be invitations for professional campaign teams inside and outside of the party to flood its lists with temporary members in the style of an old delegate selection meeting.

Would this slam the door on ambitions to recruit tens of thousands of members who are women, racialized, First Nations, or other equity-seeking groups? I would argue that the last people you should rely on for this important work are organizers for leadership campaigns, looking for votes on a ballot for one minute. Building a strong, diverse, and real membership is 365-day-a-year work for party offices and riding associations. There aren’t any shortcuts—certainly not during leadership campaigns.

Finally, leadership campaigns should last for 36 days—the minimum length of a federal election campaign. This leaves little time to game the contest but plenty of time for candidates to get their nominations in, and then to join a cross-Canada tour to speak to members.

How would that look? Well, even in a short five-week campaign, a series of leadership town halls in each of the provinces and territories would take up only 13 evenings on the campaign trail, presumably building momentum and interest along the way. The result would be an informed membership, with the party presumably benefiting from earned media coverage.

Then at the end of the campaign, engaged members would vote in an online preferential ballot, results to be announced at a lovely unity event.

And finally, here is a piece of advice over the fence to Tories and anyone tempted to copy their system. Handing power to decide your leadership to your weakest ridings with the fewest members got you Andrew Scheer and got you the current premier of Ontario. Think about that.

Brian Topp is a former president and national campaign director for the New Democratic Party of Canada, and made it to the last ballot as a candidate for the NDP leadership in 2012.