‘Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons’: Behind Every Great Man

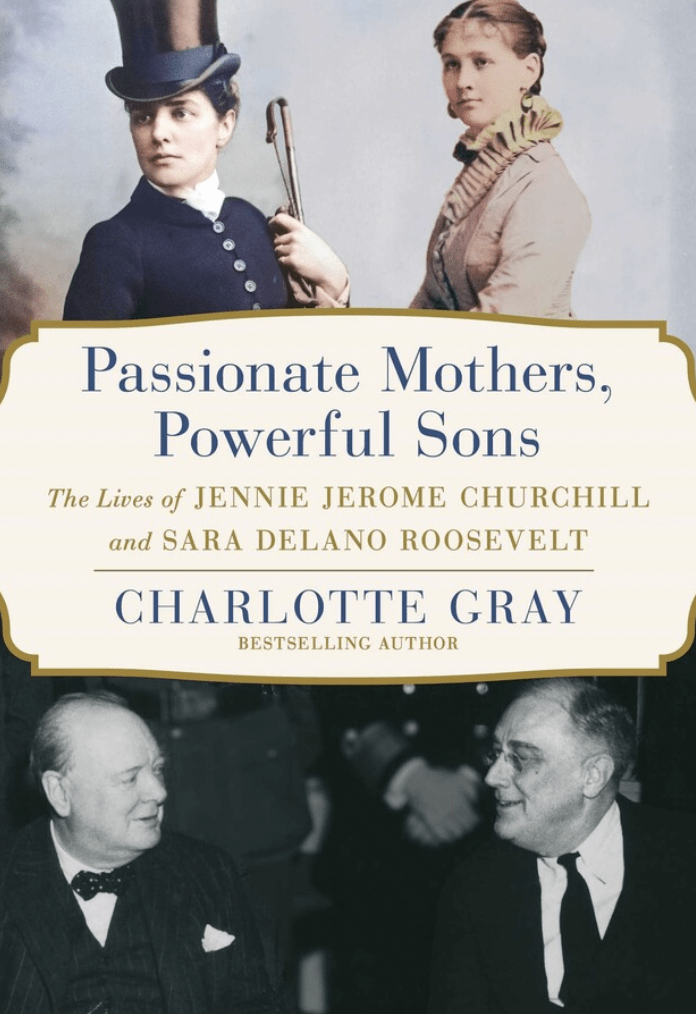

Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons: The Lives of Jennie Jerome Churchill and Sara Delano Roosevelt

By Charlotte Gray

Simon & Schuster/September 2023

Reviewed by Anthony Wilson-Smith

August 16, 2023

Well-spoken, well-connected, and seemingly at ease in almost any environment, Charlotte Gray is something of an anomaly among authors: a writer so engaging that she could fit comfortably alongside the subjects she chooses for her books. That is no small claim, because the British-born Gray – who has lived in Canada for more than a half-century after arriving here at 21 – has a keen eye for compelling characters matched by her ability to bring new information and a fresh take to their circumstances. Her dozen books to date cover topics ranging from the life of inventor Alexander Graham Bell to high-society murders to the 19th century Klondike rush.

Now, Gray’s newest book, Passionate Mothers, Powerful Sons: the Lives of Jennie Jerome Churchill and Sara Delano Roosevelt, offers expansive settings and characters that are an ideal match for her formidable strengths as researcher, social interpreter and always-elegant writer. As the title suggests, it’s an up-close look at the mothers of Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, two of the most important figures of the last century as prime minister of Great Britain and president of the United States during the pivotal years of the Second World War.

Many previous studies of both men have given the two women small, often backhanded credit for their roles in shaping their sons’ characters. The thrice-married, American-born Jennie Jerome Churchill, Gray writes, “continues to be shoehorned into the wicked seductress stereotype — too colorful, too promiscuous, and too spendthrift.” Sara Delano, Gray observes, “has suffered a different reversal of reputation, but she too is now saddled with a misogynist trope” so that she is now seen as “smothering and manipulative”. She further suffers by comparison with her son’s wife, Eleanor, whose reputation grew after her husband’s death in lockstep with her emerging public enmity toward Sara, her mother-in-law.

Gray argues compellingly that each mother played active and, overall, very positive supportive roles well into their sons’ adult years. Lady Jennie Randolph Churchill, as she was commonly known, neglected Winston and younger brother Jack as children but threw her all into promoting Winston in particular in adulthood. Sara was a constant, forceful presence through Roosevelt’s life — sometimes, Gray acknowledges, to suffocating effect. Both were particularly supportive when each man struggled at times with doubts and failings.

As is generally acknowledged, Winston Churchill was brilliant but erratic, tempestuous, tortured by his complex relationship with his father, Randolph, and seemingly always deeply in debt. Franklin Roosevelt was, despite his genteel manners, strikingly handsome appearance, and family position at the peak of New York society, initially lazy and rudderless, plagued by inner doubts and a deep fear of conflict (especially with his mother) — a man whose true character was forged, by his own admission, through the trials of his polio.

Both mothers were almost obsessive in advancing their sons’ careers, though in dramatically different ways. Born in the same year – 1854 – in close geographic circumstances (Jennie in New York City, Sara in the wealthy Upstate enclave of Newburgh), the two women in many ways could not have been more different. Jennie’s father, Leonard Jerome, was a self-made man who careened through financial fortunes, losses and affairs with various women with equal carelessness. Despite that, he was genuinely devoted to his three daughters (and, after a fashion, his wife). No matter how precarious his situation, he always found a way to help the girls financially as adults.

Gray tells both womens’ stories with a level of detail and immediacy that collapses for readers the dozens of decades since they lived and died, making us care about who they were and how it shaped the men they’d made.

Sara Delano lived a rarefied existence on a huge estate in the Hudson Valley with a family that took pride in a life of relentless stability and moral rectitude. (That overlooked the fact that much of the family income at one point was derived from her father Warren’s sales of opium in China.)

The Jeromes were notorious big spenders, even when they couldn’t pay their bills. In the most rarefied social circles of New York, they were unwelcome. The Delanos lived quietly, never had money worries, and sat atop their social circle. Jennie Jerome and Sara Delano did share the advantage of striking appearances. Jennie was considered one of the great beauties of the day while Sara, exceptionally tall, with thick long hair and a solemn expression, was statuesque and imposing.

No matter in what corner of the English-speaking world they were born, the same unwritten rules applied to all women in the late 19th century. The only way to have influence was to either be from a well-connected, wealthy family, or to marry into one based on beauty and charm. Any of those qualities could be sufficient, while their absence altogether meant a life of precarious security and little consequence.

As young women, both travelled – as one did in wealthy American circles then – to Paris because it was seen as the world’s most culturally vibrant, sophisticated city. Jennie went on to London, where she met Randolph and the two were immediately smitten. They married too quickly for Jennie to discover the wild mood swings, outrageous behavior and mental health challenges that came to dominate Randolph’s life (all amplified by his drinking). After years of their tempestuous relationship, even as his notoriety as a politician rose and fell, he became too erratic to be relied upon for anything. She nonetheless stayed by him until he died from what was believed to be long-standing syphilis at age 45 (some historians dispute that diagnosis).

Sara showed every sign of becoming a spinster until, at 26, she met James Roosevelt, a widower twice her age who was a family acquaintance. He resembled her father in his restrained behavior and fondness for ritual, and was considered ‘suitable’ socially. They married after a brief courtship. Sixteen months after the wedding, Sara gave birth to the 10 lb. Franklin and almost died in the process. She was told to not have any more children.

Gray tells both womens’ stories with a level of detail and immediacy that collapses for readers the dozens of decades since they lived and died, making us care about who they were and how it shaped the men they’d made. She vividly illustrates how restricted were womens’ lives and expectations – and how some of those attitudes linger today. She frequently demonstrates how strategically and successfully Jennie planned her social forays to the political benefit first of husband Randolph and later of Winston. Yet others describe those efforts differently: the noted Churchill historian Andrew Roberts saw such meets as evidence of her ‘socially accomplished if somewhat vacuous life.’ William Manchester, whose multi-volume Churchill biography is one of the best known of many written, wrote snidely that Jennie’s death, which resulted from a slip while coming down a flight of stairs, was caused ‘appropriately’ by a pair of fashionable shoes.

Sara, meanwhile, who was seen fondly by the general public at the time of her death, suffered in the aftermath by comparisons with Eleanor, who showed her bitterness toward her mother-in-law more openly after Franklin’s death even as her own reputation rose. Gray writes that Eleanor “portrayed Sara as snobbish, domineering and unkind” and notes that Eleanor wrote that “Franklin’s children were more my mother-in-law’s children than they were mine.”

Through all 356 pages, Gray makes a compelling case for her characters’ achievements, but is never shy of acknowledging their faults. As she writes in the final chapter, “Maybe Sara was imperious. Perhaps Jennie was flirtatious. But is that the only way to remember two women who, despite the suffocating constraints of the time, took charge of their lives and worked hard to help their sons?”

The answer is as self-evident as Gray’s case is well-argued. By challenging traditional presumptions so compellingly, the author reminds us of an essential truth: while people’s lives and events only happen once, there are countless ways to interpret them. This engaging and thoroughly entertaining book makes for one of the most finely-drawn – and most welcome.

Contributing Writer Anthony Wilson-Smith is President of Historica Canada and former Editor of Maclean’s magazine.