Policy Constitutional Primer: Dissolution and Governing During an Election

Philippe Lagassé

August 15, 2021

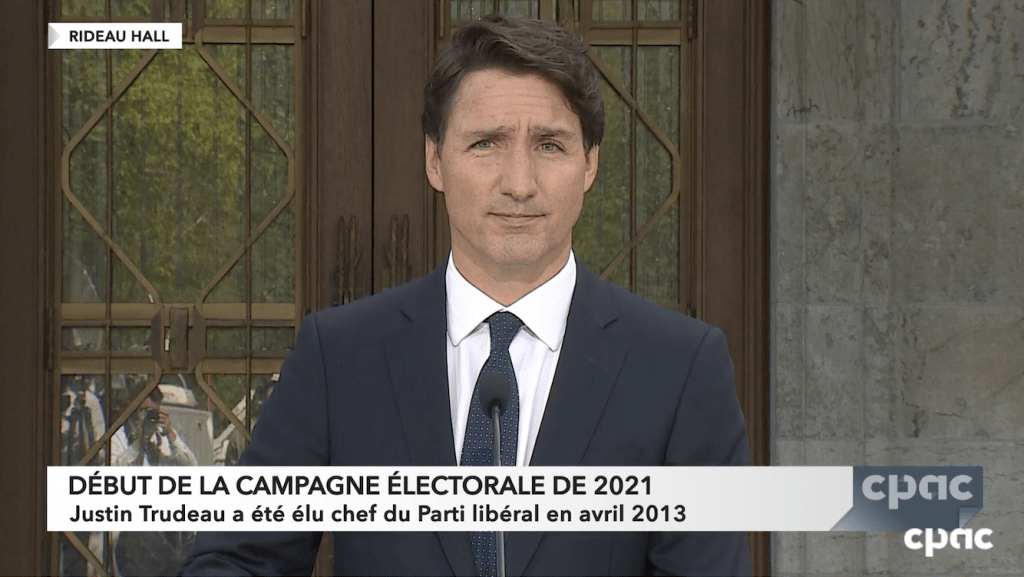

Parliament has been dissolved and Canadians will elect a new House of Commons on 20 September. As we head to the polls in the middle of a global pandemic, it is important to remember a few constitutional realities.

First, the governor general had no real discretion to deny the prime minister’s request to dissolve Parliament, despite the pandemic and the fixed date election law. The governor general can only refuse a request to dissolve Parliament if two conditions are in place: first, if Canadians had already been to the polls within the past six months to a year; second, that there is an alternative government that could command the confidence of the Commons. Neither of these conditions held this summer. The last election was nearly two years ago and none of the opposition party leaders claims that they could form a viable government. The fixed date election law, moreover, explicitly preserves the governor general’s authority to dissolve Parliament at any time, a power that the Queen’s viceregal representative only exercises on the advice of the prime minister. While we can debate the propriety of dissolving a Parliament that can still ‘work’, and whether the spirit of the fixed date election law is meant to prevent early election, the letter of the law and the constitution are clear: dissolution is the prime minister’s call and the governor general can only refuse in very specific circumstances.

Second, we still have a government. The prime minister and cabinet remain in place and are constitutionally responsible for all governing matters. Dissolution only brings this Parliament to an end. It has no legal effect on the cabinet, which is an executive body, with the prime minister appointed by the governor general and ministers appointed by the governor general on the binding advice of the prime minister. According to constitutional convention, the prime minister and cabinet should hold the confidence of the Commons or be seeking to regain it, but legally speaking the governing ministry is not connected to the life of a Parliament. During an election, cabinet remains in place to make governing decisions and exercise executive functions.

Third, the prime minister and cabinet are supposed to respect a ‘principle of restraint’ during an election. In practice, this means that the ministry should not enact policies that could bind a future government, nor should they make decisions that are not routine or necessary for the public interest. As an example, the government should not be signing any large contracts during the election. But this ‘principle of restraint’, often called the caretaker convention, does not prevent the government from continuing to engage in international negotiations that cannot be paused while Canadians vote. The prime minister and cabinet, furthermore, are entirely within their rights and responsibility to make decisions related to managing the pandemic. In fact, part of the reason the legal powers of the ministry are preserved during an election campaign is that we need the prime minister and cabinet to act during emergencies such as COVID-19. The ‘principle of restraint’ comes to an end once the prime minister meets the Commons after the election or when another party leader is sworn as prime minister.

Fourth, no matter what happens on election night, the prime minister remains in office until he resigns or is dismissed by the governor general. This is why the prime minister can meet the Commons first, regardless of how many seats another party wins. Stated differently, what happens on election night does not have a direct effect on who holds the prime ministership. If another party wins a majority of seats on election day, the prime minister will announce his resignation; if he has no chance to hold confidence, Trudeau will bow out gracefully. On the other hand, if the Liberals win fewer seats than another party, and Trudeau thinks he can broker a deal with a smaller party to maintain confidence, he can remain in office and meet the Commons. While it is customary that the party with the most seats governs, this isn’t a constitutional convention, nor is it a legal requirement.

Fifth, if Trudeau wins enough seats to maintain confidence, he will not be forming a new government. The Trudeau ministry will simply keep going. He will not be the prime minister-designate. He remains the prime minister, full stop. Here again, it is important to remember that the legal status of the prime minister and cabinet are not tied to the life of a Parliament. Ministries can span multiple parliaments and a single parliament can have more than one government. That said, Trudeau will probably choose to hold a swearing-in ceremony for cabinet and he may want to be sworn in again as prime minister. Although new ministers or those who change portfolios do need to be sworn in, the prime minister does not. If Trudeau does get sworn in again, it will be for symbolic purposes, not legal or constitutional ones. It is not accurate, therefore, to say that the Liberals will be forming government if Trudeau can hold confidence; the prime minister just keeps governing.

Finally, if Trudeau happens to resign on election night or shortly thereafter, the governor general will commission another party leader to form government. If this occurs, the new leader will be titled the prime minister-designate, meaning that they have been commissioned to form a government and are entitled to have support from the public service to prepare to govern. The prime minister-designate will only become prime minister once they are formally sworn-in by the governor general, usually two or three weeks after they have been commissioned to form a government. Under no circumstance do we have a prime minister-elect since it is an appointed office. The only body that is elected at the federal level is the House of Commons.

Contributing Writer Philippe Lagassé is associate professor and Barton Chair at Carleton University.