An Oxbridge Pilgrimage with an Irish Interlude

Arlene and Bob Rae in Ireland/ambassadorial selfie

Bob Rae

July 24, 2023

Travelling as a diplomat is not the same as travelling as either a politician or as a private citizen. It is both less and more dangerous as a rhetorical minefield than retail politics, because while I’m representing something larger than myself— in this case my country rather than my party — the potential for creating an international incident is significantly greater. The upside of having that asymmetrical value attached to your words while abroad is that, diplomacy being a 24-hour-a-day endeavour, you can have an impact on the world simply by being out in it. And if you keep talking through the gaffes, they sometimes go unnoticed.

This summer, I spent a stretch of June and early July on an Oxbridge pilgrimage — my dad, Saul Rae, and I studied at Oxford and my mom, Lois Esther George, at Cambridge — with an Irish golf and foreign policy interlude in between.

From Oxford for the 120th anniversary of the Rhodes Scholarships to the links at Baltray and a diplomatic panel in Dublin, it was on to Cambridge for the Canadian Institute for Advanced Studies and the Cambridge Lectures.

I travelled to Oxford by plane, then bus, arriving at the Gloucester Green station from Heathrow at about noon. Reading a brilliant biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer American Prometheus — a life much in the news these days with the release of Christopher Nolan’s film — so much to think about.

From the bus station, it was just a short walk to Balliol College (above), whose arched entrance I first crossed as a Rhodes Scholar in September of 1969. There is an irony in the 120th anniversary event, which celebrates the death of British mining magnate, South African politician and hyper-imperialist Cecil Rhodes as the precondition for the will that created the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. When I won the scholarship, it was only available to men, which means that, in all likelihood, I would not have been a successful candidate had women been eligible for the prize.

The Rhodes Trust is undergoing a renaissance at the moment. A financial crisis twenty years ago was followed by a generous gift from John McCall McBain, a Canadian who won the scholarship in 1980, an unprecedented outbreak of philanthropy from many (including scholars), and great leadership from a new generation of trustees and wardens who have expanded the range of countries eligible to send students to Oxford and many more opportunities to study and travel than ever before.

The result was a 120th anniversary reunion far more diverse than the young, mostly white men who came in my year. My first reunion event was a coffee (we are getting older) with friends from my year, and, happily, a lot more talk about the present and future than the long discursions into nostalgia that too often accompany these events.

The dinner that first night was a gathering at Balliol for all scholars who were college members, and it was a lively celebration. Sitting next to a former head of the college, Andrew Graham, the conversation quickly turned to his expressing profound regret about Brexit, an inevitable focus of discussion over my whole trip with many others in both the UK and Ireland. Graham was now expending much effort creating programs and scholarships that would continue to encourage educational exchanges between Europe and the UK. From scientists no longer able to get the benefit of major research grants, to artists similarly shut off from access to a vast market without work permits and passports, the story was the same: by renouncing the Treaty on European Union, Britain had scored an “own goal” with consequences that are far from over.

A chat with a Canadian teaching and researching on public opinion, Philip Howard, allowed me to tell the story that my Dad, Saul Rae, after finishing his doctorate at the London School of Economics, spent a post-grad year at Balliol just before the war. It also happened to be the year of the Oxford byelection, where the master of Balliol, A.D. Lindsay, was a candidate against the Conservative, Quentin Hogg, who would be the eventual winner. Saul’s field of study was the nascent realm of public opinion, and he covered the by-election. Polling in those days meant door-to-door canvassing in an effort to get an accurate sample. He predicted a narrow Hogg victory and wrote it up for the Public Opinion Quarterly.

The next day, I joined three remarkable women and a moderator to discuss the state of the world in the 120th anniversary panel on geopolitics and global affairs.

Eleanor Brown (above) is a Jamaican law professor teaching at both Fordham and Penn State. Trudi Makhaya is a South African economist advising President Cyril Ramaphosa, and Meg Whitman has been CEO of two major companies, a candidate for governor of California, and is now the US ambassador to Kenya. Our moderator, Brian Wong, had just completed his doctorate on the rights and obligations of citizens living in authoritarian countries. It was a lively conversation — touching on the current “polycrisis”, its dramatic impacts on global wellbeing and solidarity, and the steps we need to take to deal with it.

As in all such discussions and debates, the diagnoses and descriptions of the crisis are at least a beginning in raising awareness. The central irony of our times is that our politics is becoming more influenced by nationalism just at the time when global solidarity is more essential than ever. The international nature of the audience naturally made it receptive to the arguments and experiences we all shared, but it is national leaders and governments who are going to need to push for decisions that will make the essential difference.

The event was held in the building known as the Examination School, where over 50 years ago I wrote my MPhil exams over two days, followed by an oral test known as a “viva”, all while dressed in “sub fusc” (from the Latin sub fuscus, meaning dark brown, but most of it is black). To my knowledge, there are no photos of this ritual indignity, which was followed by exam results being posted publicly on a wall outside.

My wife, Arlene, joined me for the trip to Ireland. It was not all business. A dear friend of mine, Charles Scott, died last summer. We used to play golf with Charles and his wife, Cathy, at the County Louth Golf Club, better known as Baltray. Our memorial visit did not disappoint — we played through sun, wind and rain over three rounds, with many tears shed as we celebrated Charles’s life.

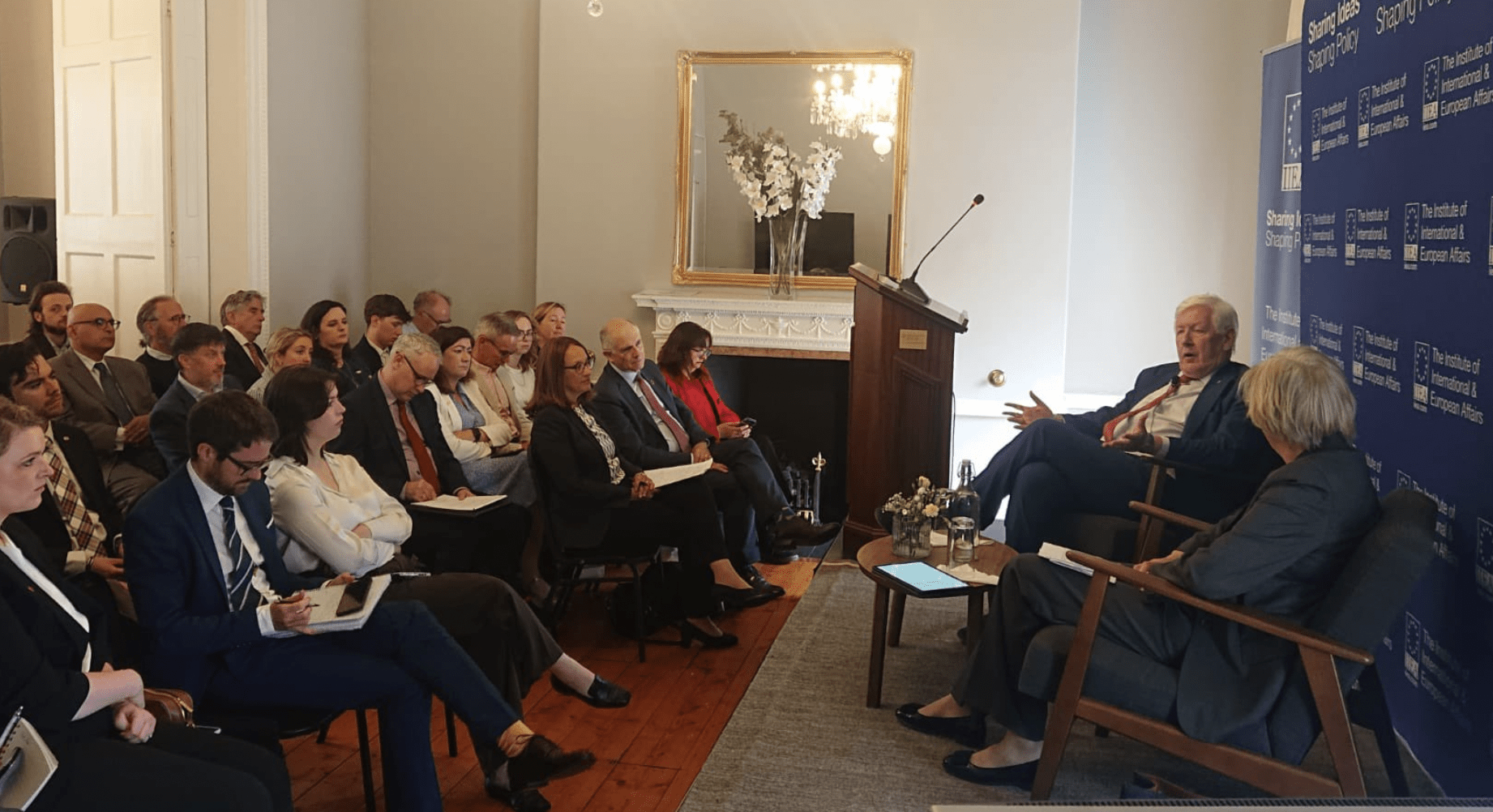

We then headed to Dublin and the Irish Institute of European and International Affairs (IIEA) for the diplomatic symposium Standard-Bearers for Multilateralism: Canada, Ireland, and the UN. The conversation at the Institute (above), where I was joined by Canada’s ambassador to Ireland, Nancy Smyth, echoed some of the themes from the Oxford visit, but with a greater focus on the opportunities and obligations of middle powers with strong international instincts, including Ireland and Canada. Brexit has created many investment opportunities for companies seeking to gain access to European markets, and Ireland’s long engagement with the United Nations has made them important partners for Canada. The group running the Institute are bright and entrepreneurial, and there are many opportunities for Canadian think tanks to engage with the IIEA.

Cambridge is the home of the Cambridge Lectures, founded by the late Paul Martin Sr. when he was the High Commissioner to the United Kingdom in the 1970s. Martin had studied at Cambridge and, after visiting the university again, decided that a Canadian conclave there, at a major centre for international law, would be a good idea. The Canadian Institute for Advanced Legal Studies convenes the meetings every two years, in July. They are attended by several hundred judges and lawyers, including, this year, six judges from the Supreme Court of Canada.

I was asked to join the group for a “fireside conversation” on the threats to the rule of law in the world today. The French philosopher Blaise Pascal once famously remarked that “Law without power is impotent, but power without law is tyranny.” We all know that respect for the law in our own lives depends not only on personal feelings of morality, but also the probability and expectation of enforcement and consequences for illegal behaviour. The challenge for international law is that while institutions are stronger than they have been in the past, there are simply too many new ways — especially having to do with the borderless possibilities for criminality of all kinds and at multiple levels enabled by new technology — in which laws are flouted and ignored. It is this critical weakness that we have to continue to remedy.

We often simply blame institutions like the United Nations for this failing, but this ignores the fact that it is nation-states that have created limits on what these institutions can do. The veto power of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council is one such limitation. But the real limit of enforcement is the fear that is created by nuclear arsenals in the control of powers that are capable of enormous destruction if threatened with challenges to their power. This makes the world a dangerous, as well as an increasingly unequal, place. At Cambridge, there were lively questions and good conversations all round, as well as many stimulating presentations from British judges and experts.

Cambridge is, dare I say it, even more beautiful than Oxford, and Arlene and I had a chance for a great walk to Newnham College (above), which my mother, Lois, attended as a student in the 1930s. Women could attend classes and write papers and exams, but not actually graduate, until 1948. She finally received her degree from Cambridge on her 97th birthday. Newnham remains proudly a women’s-only college and it is an inspiring and beautiful place.

We also had a chance to visit family — my cousin Robert George, a retired police officer, lives nearby, and we had a chance to catch up.

On returning to the UN, I reflected that explaining what modern diplomacy is all about — the issues that we deal with, and the consequences of not meeting the tests of our current history — is far more important now than ever. The increased engagement of global citizens is indispensable, and we cannot retreat from the decisions that will make progress possible. To be able to spend some time in places that had so many memories made that reflection all the more meaningful.

Bob Rae is Canada’s permanent representative to the United Nations.