Policy Dispatches: Defying Putin, Heeding History and Paying Homage to Bowie in Berlin

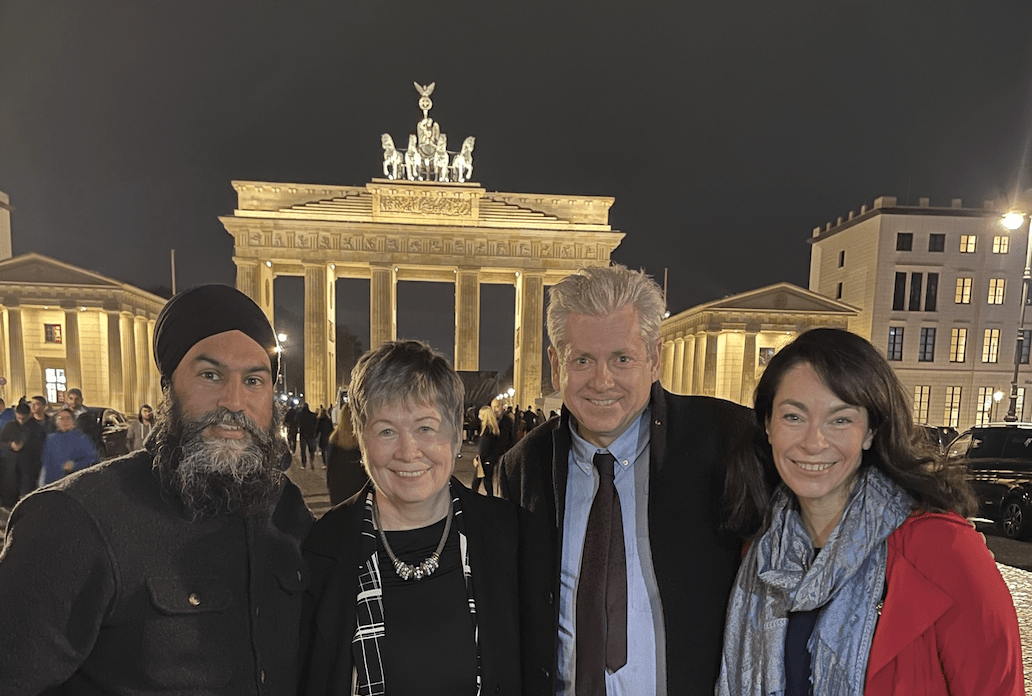

NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh, NDP National Director Anne McGrath, MP Charlie Angus and MP Heather McPherson at the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin, Nov. 4, 2022.

NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh, NDP National Director Anne McGrath, MP Charlie Angus and MP Heather McPherson at the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin, Nov. 4, 2022.

Charlie Angus

November 13, 2022

I just spent a week in Berlin as part of a Canadian New Democratic Party delegation meeting with Chancellor Olaf Scholz and senior government officials of the ruling Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, or Social Democratic Party (SPD). The SPD — Germany’s oldest party, founded in 1875, and centre-left on the spectrum — is a sister party of our NDP, and they were interested in meeting our leader, Jagmeet Singh. Our small delegation included Jagmeet, NDP National Director Anne McGrath, NDP MP for Edmonton-Strathcona and Foreign Affairs critic Heather McPherson and myself.

In the preparatory work leading up to the trip, we knew this would be more than a series of perfunctory meet-and-greets. The German government is keen to forge much stronger links with Canada, so our discussions were long, detailed and covered a wide array of topics: The Germans want to learn more about Canada’s immense potential for clean energy; as a party long used to coalition government, the SPD was intrigued by our supply and confidence arrangement with the Liberals; they were interested in the tools we are using to tackle “greedflation” and to provide economic relief in the face of rising energy and food costs; Germany is also dealing with unprecedented levels of immigration, and they wanted to know how Canada had forged its multicultural identity. Our exchanges quickly blew past surface questions to the real conversations that happen beyond the ticking of boxes on a checklist.

And everywhere we went, people asked about the Ottawa blockade of last winter. The Germans are deeply concerned about the destabilization of democracies around the world. The Gong Show Occupation played on screens around the world, and the Germans asked probing questions about the rise of extremism, whether certain political parties are exploiting disinformation and if Canada’s tradition of tolerance and democracy is under threat. We assured them that this was not the case.

Such intense interest in Canadian politics is not something we’ve tended to see in Europe. The shadow of the United States looms large over perceptions of the continent. Europeans often see Canada as a benign, blank slate — as if our immense nation could be summed up with a clip of the RCMP Musical Ride choreographed to a Céline Dion soundtrack.

German officials in foreign affairs, energy, labour, housing, and economy were deeply interested in our authentic Canadian reality and they made their reasons known right up front: the war in Ukraine has upended everything. Germany finds itself next to the front lines of a massive European land war. The Russian regime has turned the gas taps off to Europe, threatening to make Germany an economic hostage of Vladimir Putin’s pathocratic regime.

The energy crisis may be severe, but German officials wanted us to know that they have filled their stocks of gas for the coming winter. Their focus is to accelerate their independence from fossil fuels. They want to see whether Canada can provide long-term supplies of large quantities of hydrogen.

Which is why the German government was so keen to discuss clean energy possibilities with us. They know New Democrats have been working with energy worker unions in western Canada to push the Trudeau government to make a major commitment to building a clean energy economy. The SPD sees this as a hugely positive step because they are looking at the energy crisis through the lens of the growing climate crisis.

Canada’s powerful oil and gas lobby has been making the pitch that the best way to “help” Germany is by promoting the construction of controversial LNG or oil pipelines. The Germans are well aware that this infrastructure would take years to build, and they would be locked into long-term fossil fuel contracts. They aren’t going down this road. The energy crisis may be severe, but German officials wanted us to know that they have filled their stocks of gas for the coming winter. Their focus is to accelerate their independence from fossil fuels. They want to see whether Canada can provide long-term supplies of large quantities of hydrogen. This would be a hugely positive development for both countries.

The clean energy conversation was part of a series of economic policy discussions on issues ranging from resource potential (hydrogen, critical minerals/forestry) to housing and inflation responses. We were not there to undermine the work of our trade negotiators, or of the Liberal government. Putin’s war has compelled Canada to step up and build alliances with countries of shared values. As New Democrats, we pledged to work with our sister party through our own parliament to build stronger ties between Canada and Germany.

With Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Nov. 5, 2022

With Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Nov. 5, 2022

We met Chancellor Scholz at the SPD’s Debattenkonvent, or debate convention, on November 5th. This was the day after his whirlwind meeting with President Xi Jinping in Beijing. Germany has strong economic links with China and Scholz was applauded by the party membership for using this influence to push Xi to call on Russia not to use to the nuclear option. Berlin is deeply concerned that Russia’s war on Ukraine war could spill into a much larger conflict.

And yet, in our meeting, Chancellor Scholz told us bluntly that Germany would not be held hostage by Russia. Berlin has taken extraordinary steps to break its energy dependency and is looking for allies to join them in defending democratic principles. Scholz wants to build our bilateral relationship on shared democratic values, fair trade agreements and climate responsibility. As Canadians and as New Democrats, we made it clear that we share these values.

This shared vision was articulated in a public conversation during the Debattenkonvent on November 5, when Jagmeet Singh joined SPD Chair Lars Klingbeil and other European politicians and foreign affairs experts in discussing a collective response to Putin. The SPD forum was similar in many ways to the NDP forums I have participated in over the years. Normally, such an audience would be calling on the leadership to promote peace and negotiations. But it was evident that German Social Democrats were looking for a very strong and bold line against Putin’s aggression. As one senior SPD minister said to me over coffee, “A year ago it would have seemed inconceivable that we would be living through a major war, with tanks on European soil.”

Immediate History

Berlin is a phenomenal city, but it was much more than a scenic backdrop for the Canadian delegation’s selfies. The European Union’s largest city by population, Berlin’s biography — from capital of the Kingdom of Prussia to capital of the Weimar Republic to capital of Nazi Germany to quartered among the Allies and the Soviet Union to bifurcated by the Berlin Wall in 1961 to spectacularly reunified with the fall of the Wall in 1989 — is a microcosm of modern history.

But the darkest chapter of that story — Adolf Hitler’s rise to power, the Second World War and the Holocaust — teaches us why the conversations we held with our German colleagues are so essential now. In Berlin, history is lived in the here and now as a national imperative, which is how I came upon the story of Hilde Coppi.

On our arrival, our hosts at the Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung (a social democratic foundation with a mandate to promote democracy) offered to take us on a sightseeing tour of the city. I was keen to see the remnants of the Wall, check out Checkpoint Charlie and get my photo taken at the Brandenburg Gate. Jagmeet, Heather, Anne and I were picked up in a small bus. But we’d barely driven two minutes when our guide pulled over on a quiet side street and asked us to step out.

“This is our first stop,” he said.

It seemed an odd spot for a tourist stop. We crossed over to an austere block of offices with an immense inner courtyard. When I asked why we were here, our guide said, “This is where the Nazis murdered Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg and the soldiers who attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944.”

This was the Bendlerblock — the former headquarters of the Wehrmacht high command, now home to the German Resistance Memorial Centre. The empty courtyard felt eerie.

Wikipedia

The centrepiece of the space is now a large bronze statue of a naked man, hands bound, standing on the spot where von Stauffenberg and three others were executed by firing squad. In the days following the failed coup — dubbed Operation Valkyrie (you may know it from the 2008 film in which Tom Cruise played von Stauffenberg) — an estimated 7,000 people were rounded up and approximately 4,980 of them were executed as a public deterrent to further plotting.

As we left the courtyard, we saw large photographs adorning the walls. I recognized those of student resistance leader Sophie Scholl, beheaded by the Nazis in 1943, and the murdered religious thinker Dietrich Bonhoeffer, hanged in 1945 for conspiring in Operation Valkyrie. But the other faces were unfamiliar.

Hans Koppi/Wikipedia

That’s how I met Hilde Coppi (above). She smiled out from a large photograph. She seemed young and carefree. I needed to know her story. I discovered that she was arrested along with her husband, Hans, in 1943 for being active in a Berlin resistance group the Nazis labelled the Red Orchestra. Hans was executed, but because Hilde was pregnant, the Nazis kept her alive long enough to give birth and nurse her baby, Hans Jr. On August 5th, 1943, when her son was eight months old, Hilde Coppi was beheaded. Hans Jr. was raised with his grandparents, grew up to be an economist, East German political official and resistance historian, and today lives in Berlin with his wife, gallery owner Helle Coppi. They have three daughters.

Our guide explained that the centre was constructed so that people would understand the mechanisms that systematically undermined democracy and the propaganda and intimidation tactics that normalized evil, turning ordinary people into monstrously amoral accomplices.

Our hosts then brought us to the Topography of Terror museum, where we were introduced to the stories of thousands of other ordinary Germans; some were victims of the terror, others were perpetrators. The Topography of Terror centre is on the former site of the headquarters of the Gestapo and SS. For years, it had been a parking lot until, in the early 1980s, ordinary citizens began to expose the torture cells beneath. They wanted people to know what happened here. The Topography centre hosts more than two million visitors a year, many of them young German students.

Topography of Terror Museum

Topography of Terror Museum

In one of the exhibits, I saw a photograph that will stay with me for the rest of my life. It showed a group of young women and men in uniform (above). They were all laughing and having fun — as young and as carefree as Hilde Coppi had once been. It turns out that this was one of the Auschwitz murder squads relaxing after completing another hard day’s work in the mass deportation and slaughter of Hungary’s Jewish population.

Our guide explained that the centre was constructed so that people would understand the mechanisms that systematically undermined democracy and the propaganda and intimidation tactics that normalized evil, turning ordinary people into monstrously amoral accomplices.

After a well-known evolution from postwar cultural denial to more recent, controversial commemorations of the Holocaust, Berliners today don’t shy away from Germany’s Second World War history. This is why the graffiti of Russian soldiers have not been erased from the walls of the beautifully restored Bundestag legislature. It is why a key storefront at a busy commercial intersection is dedicated to the story of the late Berlin Mayor and Chancellor Willy Brandt, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate still remembered for the iconic 1970 image of him kneeling, as German Chancellor, before the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial commemorating the half-million Jews who were imprisoned there before being deported to death camps.

Amid today’s history, our hosts used the Berlin sightseeing tour for us to understand why the German people are so committed to democracy and the support of strong public institutions. The reminders are everywhere in Berlin of what any society can devolve into when the values of peace, pluralism, human rights and democracy are slowly replaced by conflict, exclusion, inequality and the leveraged hatreds used to rationalize the annihilation of freedom.

The Other Berlin

Years before Berlin became the repository for Hitler’s delusions of “Germania” – Berlin as the capital of a global Nazi empire — it was a global mecca of creativity and artistic expression. That status — memorably captured in the writing of Christopher Isherwood that inspired the musical Cabaret — re-emerged from the rubble of war, and artists from around the world returned to Berlin.

For me, as both a professional musician and a fan, no trip to Berlin would be complete without a pilgrimage to where David Bowie underwent a major musical transformation. Bowie recorded the Berlin Trilogy here at Hansa Studios — the albums Low and Heroes in 1977, and The Lodger in 1979. When first I arrived in the city, I understood why Bowie was so inspired. Today, the working class Karl Marx Platz is a wild bustle of Turkish and Syrian families. In another part of the city, I found a huge park of vendors where an impromptu rave was taking place with a busking DJ. Berliners embrace their gritty identity, and are determined to ensure that young workers and creative people are not priced out of Berlin as has happened in other global centres, including Toronto and New York. This is why the issue of housing policy and fair rents is so crucial to the city’s sense of self.

When Bowie and Iggy Pop moved to Berlin in the mid-70s, the city was even grittier and edgier. I found Bowie’s apartment on the busy urban street of Hauptstrasse in the neighbourhood of Schöneberg, which had been the centre of Weimar Berlin’s gay culture, where Isherwood and other artists worked and lived before the terror of Nazi persecution. You might walk right past Bowie’s apartment it if you don’t know what you’re looking for; if not for the street painting of Bowie as spaceman and as Aladdin Sane. A simple plaque informs passersby that this is where David Bowie lived. The plaque reads, “We could be heroes, just for one day.” When Berlin Mayor Michael Müller dedicated the plaque in 2016, he said that with the song Heroes, Bowie had written the unofficial anthem of the city. Below the display, someone had put a milk bottle containing flowers to commemorate. The flowers were fresh.

And so, even as we spent our days in meetings about the energy crisis and the humanitarian catastrophe unfolding to the east, I kept thinking that Bowie was right. Berlin makes you believe that it is possible for us to be better. That we can be heroes. Like Hilde Coppi. Like those standing up to the Putin war machine. Like those rave buskers in the park. Heroes, sometimes for even more than just one day.

Charlie Angus has been the NDP Member of Parliament for Timmins-James Bay since 2004. He is also frontman for the Grievous Angels, and a regular Policy contributor. His latest book is Cobalt: Cradle of the Demon Metals, Birth of a Mining Superpower. Policy Dispatches are pieces combining travel, policy and political writing from foreign datelines.