Policy Dispatches: Feeling a Republic’s Enduring Vitality in D.C.

David O. Johnston

March 6, 2023

Policy Dispatches are pieces combining travel, policy and political writing from Policy writers on the road.

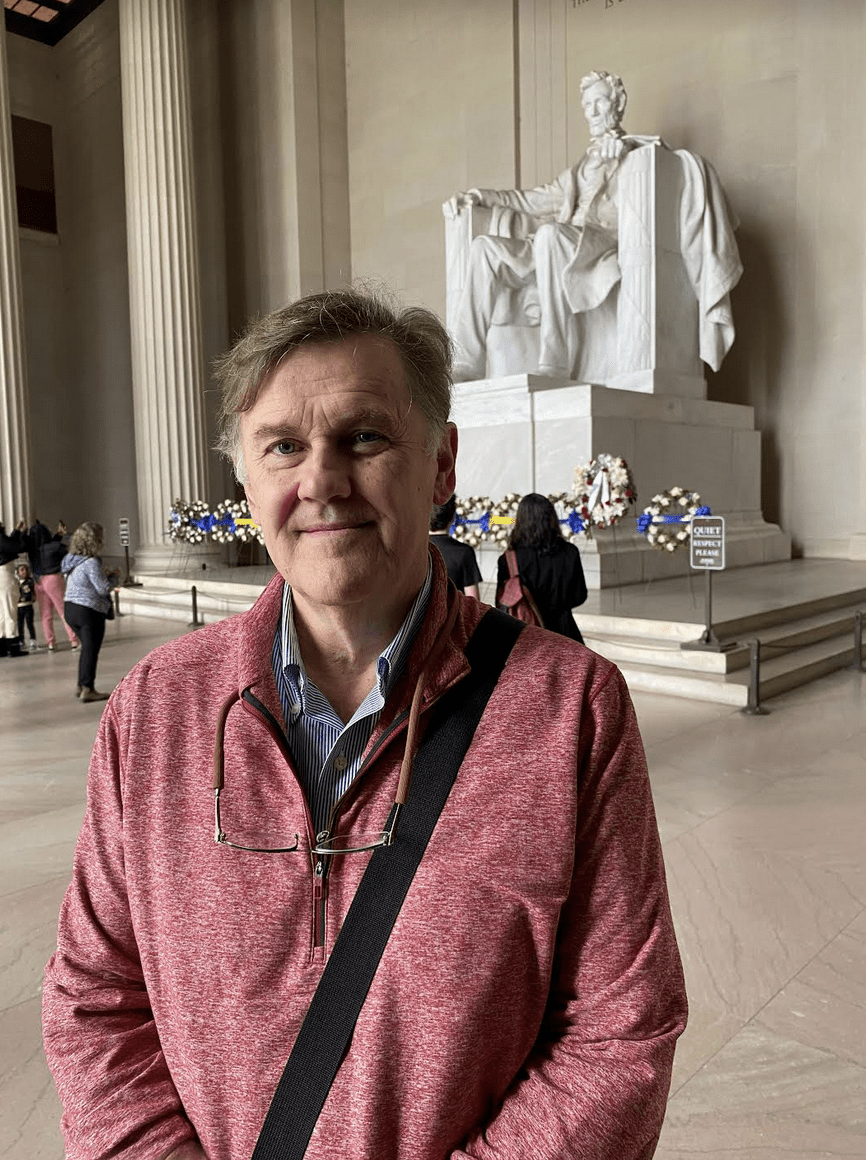

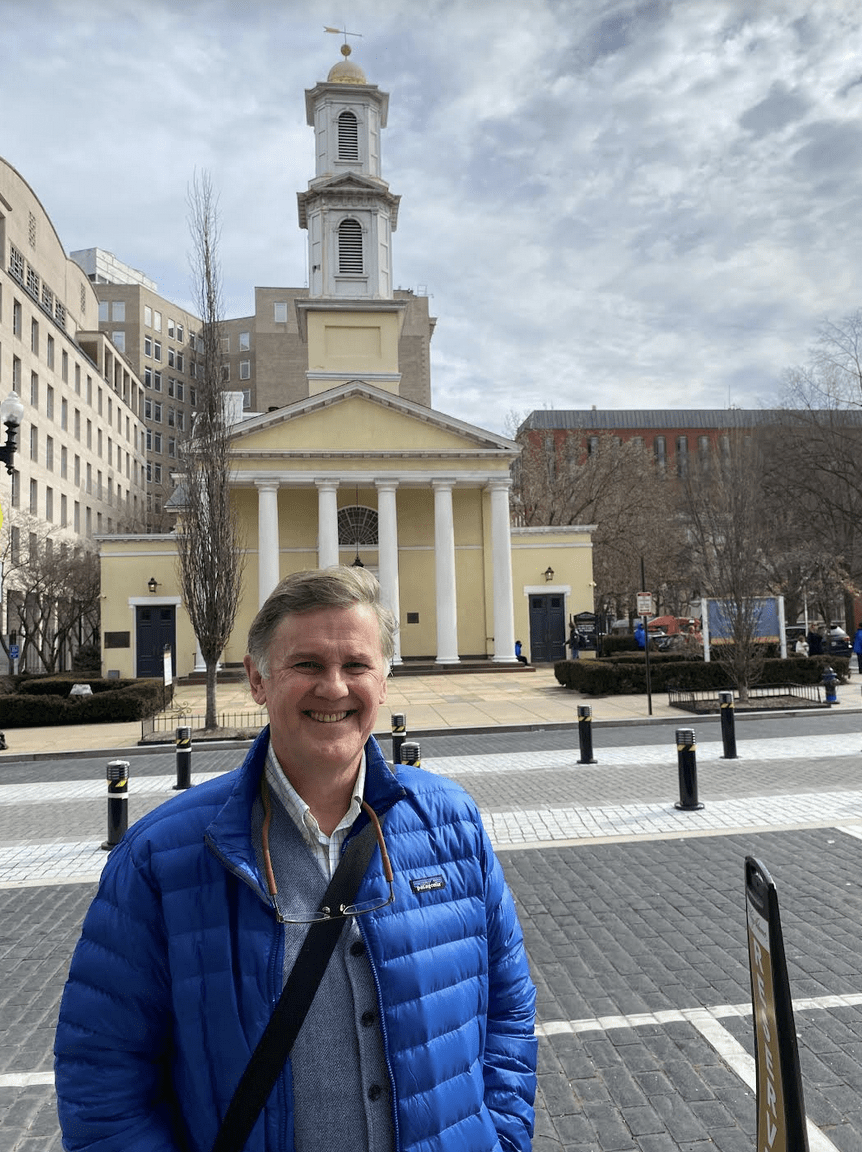

Every American president since James Madison in 1816 has attended services at St. John’s Episcopal Church at least once, which is why the little yellow church across Lafayette Park from the White House is known as the Church of the Presidents.

I first became aware of it during the coverage of George Floyd’s murder, in the spring of 2020. In different parts of Washington, street protests broke out and fires were set. One of those fires was set inside the basement nursery of the parish house of St. John’s. Police cleared the area with tear gas and in the immediate aftermath, former President Donald Trump strode from the White House to the church and held up a bible in front it, a provocative stunt open to multiple interpretations. The Episcopal bishop of Washington, the Rev. Mariann Budde, criticized the move as a photo-op in bad taste. “I am outraged,” she told CNN.

Ahead of a five-day visit to Washington in February, my wife, Cheryl Cornacchia, and I planned an itinerary that included a visit to St. John’s for the 9 am Sunday communion service. I was pleased to see that the church was hosting a speaker series that month – and that Montreal-born presidential historian Tim Naftali would be speaking about the Reagan presidency in the parish house in the hour after the service.

We were in a relaxed mood that morning because a visit that had begun two days earlier was turning out to be one of our easiest, most convenient, and interesting winter getaways yet.

We had found ourselves at loose ends in late January after we’d cancelled a three-week trip to Israel scheduled for March. We were no longer comfortable visiting the country, given the outbreak of violence since the elections of last November. By contrast, Washington is quiet these days, hotel rates in February are a bargain, there is rarely any snow in winter and the fabulous museums are mostly free; D.C. seemed like the perfect Plan B.

My wife and I flew on a direct 1h45-minute Air Canada flight from Montreal’s Trudeau Airport to Reagan National, just across the Potomac River from the downtown core. While checking in online for the flight the day before, there was a message from Air Canada encouraging us to first download the US Customs and Border Protection’s new Mobile Passport Control app, to help expedite our entry into the US at Trudeau. The app was introduced last fall. It prompts you to take a picture of yourself, upload it into the app, enter your passport information and answer a series of customs-related questions. We were happy we did. The MPC line at the US CBP control area had only six people in it, whereas there were 50 people lined up for the parallel non-MPC line, and 20 in the Nexus line. A Nexus membership costs $50 and provides for five years of border and customs pre-clearance. The MPC app is free.

Moments after our 50-seat Bombardier-200 Regional Jet swung over the Jefferson Memorial, we were on the ground at Reagan, and just five Metro stops from our downtown hotel on L Street near Chinatown. Our room at the boutique Morrison Clark Inn cost us $290 Cdn a night, a sharp discount from the $475 during the peak spring-fall tourist season.

Historic St. John’s, Church of the Presidents

On Sunday, after the service at St. John’s, we sat in on Naftali’s informative assessment of what he called “the balance sheet” of the Reagan presidency, the positives and the negatives, and how, overall, Reagan’s was a “consequential” presidency.

After he finished, I went up and introduced myself – a reporter and later editorial-page editor at the Montreal Gazette, and more recently Quebec regional representative of the federal Commissioner of Official Languages from 2014 until my retirement in 2022. At the mention of language, Naftali rolled his eyes, which did not surprise me. I had read that he told the Toronto Star in 2007 that he left his native Quebec because of the province’s language laws. While Naftali was studying at Yale in the early 80s, he convinced Robert Bourassa, then between stints as Quebec premier, to teach a course in New Haven. He worked as Bourassa’s English-language speechwriter after he returned to power, before leaving to pursue graduate degrees at Johns Hopkins and Harvard. Author of six books, he was director of the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda from 2007 to 2011.

We talked about how Canada doesn’t have the same tradition of prime ministerial libraries and museums, and I asked him if he thought this was because the executive branch of government in the US plays a more important role than it does in Canada, and if, more broadly, the US is just bigger and more consequential internationally than Canada. He shook his head.

“No, the main reason is that Canada is not a transparent country,” he said. “It is not as transparent as the United States.” There is not as much documentation, and less access to documentation, in Canada, he suggested, so not as much material for prime ministerial libraries.

I’m not sure I’d agree, but his quick reply was food for thought as we left the church and continued our day of sightseeing.

Washington is a great walking city, with a lot to see in a concentrated area. The National Mall, conceived in 1791 by Pierre L’Enfant — the French military engineer George Washington enlisted to design the new American capital — as a “public walk”, remains so today. Flanked by monuments, memorials and Smithsonian museums, its sweeping vista from the US Capitol to the Lincoln Memorial provides eye candy for history buffs and political junkies alike. The city’s core extends in quadrants NW, NE, SW, SE — unequal both geographically and socioeconomically — outward from a “compass stone” located in the Crypt under the Rotunda of the Capitol. Its topography transforms as L’Enfant’s wide avenues and stately — if notoriously unnavigable — traffic circles give way to the “real D.C.” of diverse neighbourhoods — Adams Morgan, Shaw and the U Street Corridor, the predominantly Black neighbourhoods of Southeast D.C., historic, cobblestoned Georgetown, the affluent, leafy inside-the-Beltway enclaves of Northwest, and, beyond the Beltway, the Maryland and Virginia suburbs.

As anyone who has been to Washington knows, the Smithsonian Institution operates 17 different museums in the DC area, all free of charge. Many but not all are concentrated along the Mall. These include the National Air and Space Museum, where eight new galleries opened last fall, including one devoted to the Apollo 11 moon landing. There, we saw the actual suit worn by Neil Armstrong on his historic first Apollo 11 moon walk, as well as the Columbia command module that brought the three astronauts back to earth.

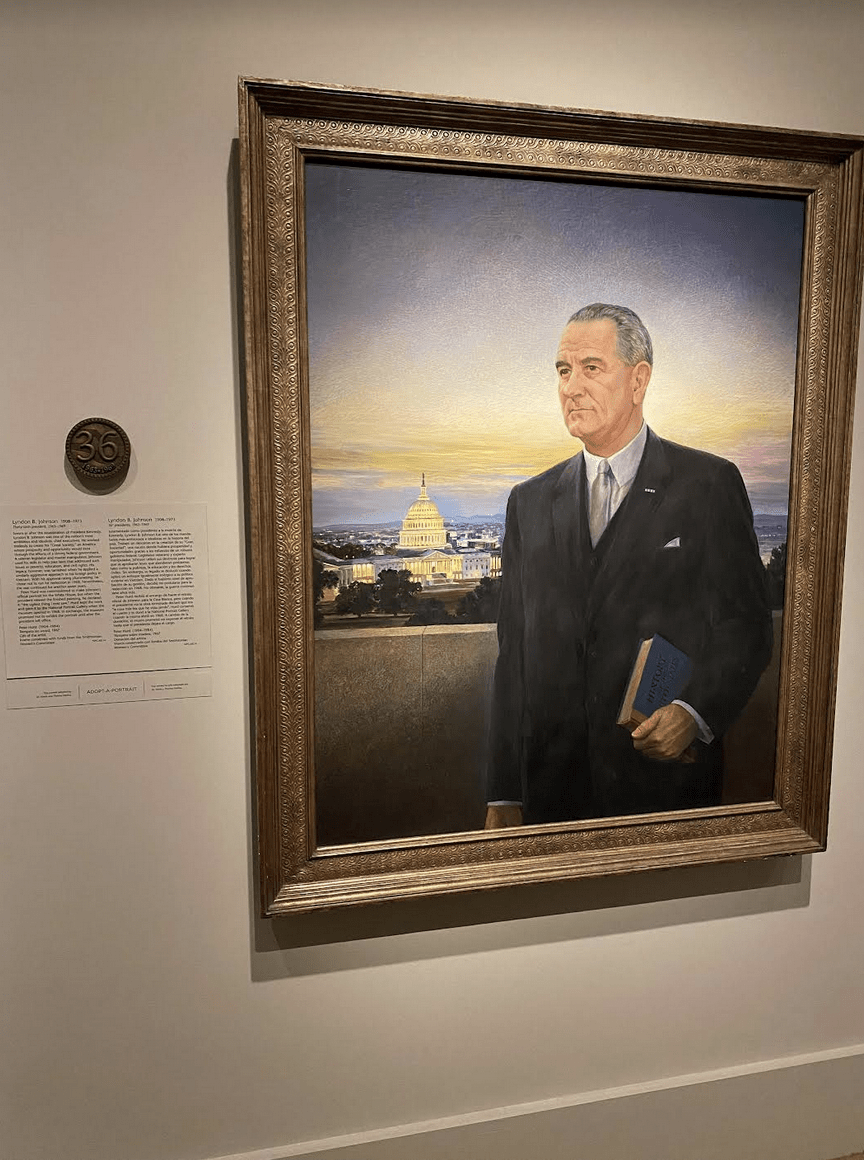

The Peter Hurd portrait of LBJ/National Portrait Gallery

At the National Portrait Gallery near Chinatown, also under the Smithsonian umbrella, we visited the gallery devoted to portraits of the American presidents. Those of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln draw the most attention, understandably. But I was struck by the portrait of Lyndon B. Johnson and the story behind it. The painting, by Peter Hurd, depicts Johnson just before sunset, standing on a fictional balcony (he refused to pose for Hurd beyond 30 minutes at Camp David) with the Capitol dome behind him. The plaque beside the painting says that when Johnson first saw the portrait, he said it was “the ugliest thing I ever saw” — a reaction reminiscent of Winston Churchill’s to Graham Sutherland’s famously unflattering portrait, which was later destroyed. Out of respect for LBJ, the museum did not display the painting until after he left office. The striking thing about it is the lightning. Johnson’s face is lit up by the setting sun and behind him, the lights of the Capitol where he held sway as Senate majority leader — “master of the Senate” per biographer Robert Caro — have been turned on. The lighting is suggestive of epiphany and denouement, of Johnson’s role as president in pushing through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, and a long struggle finally ending. Johnson is depicted holding a book, titled History of the United States.

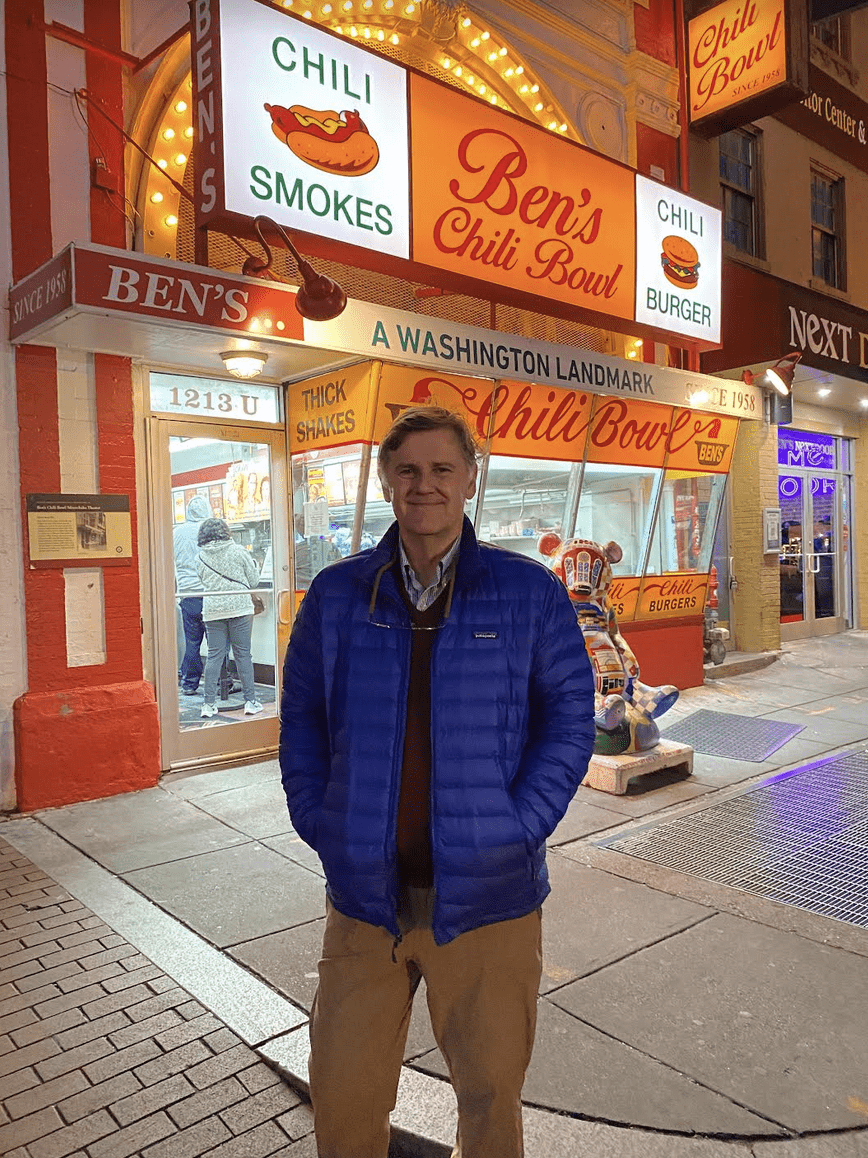

A landmark off the Mall: Ben’s Chili Bowl

As a Montrealer born and bred, I know my city has some signature fast-food treats that are tourist draws — smoked meat, “steamie” hot dogs and poutine, among them. My wife and I were curious as to whether Washington had its own defining fast-food delights. We found one – the “half-smoke”. The half-smoke is a type of hot dog. It is thicker, spicier, and more coarsely ground than a traditional hot dog, and covered in a selection of sauces. We sampled our half-smokes with chili sauce at Ben’s Chili Bowl, a DC culinary landmark that dates back to 1958 and has survived both the U Street Corridor’s gentrification and — just barely — the COVID lockdown. It has the same time-capsule charm as Schwartz’s Deli in Montreal. On the walls are photographs of some celebrity customers – among them Anthony Bourdain, Jimmy Fallon, Chris Rock, Barack Obama and former French president Nicolas Sarkozy and his wife Carla Bruni. Right beside the original Ben’s is Ben’s Next Door, which features fried catfish fingers and another Washington signature dish – Maryland lump crab cakes from nearby Chesapeake Bay.

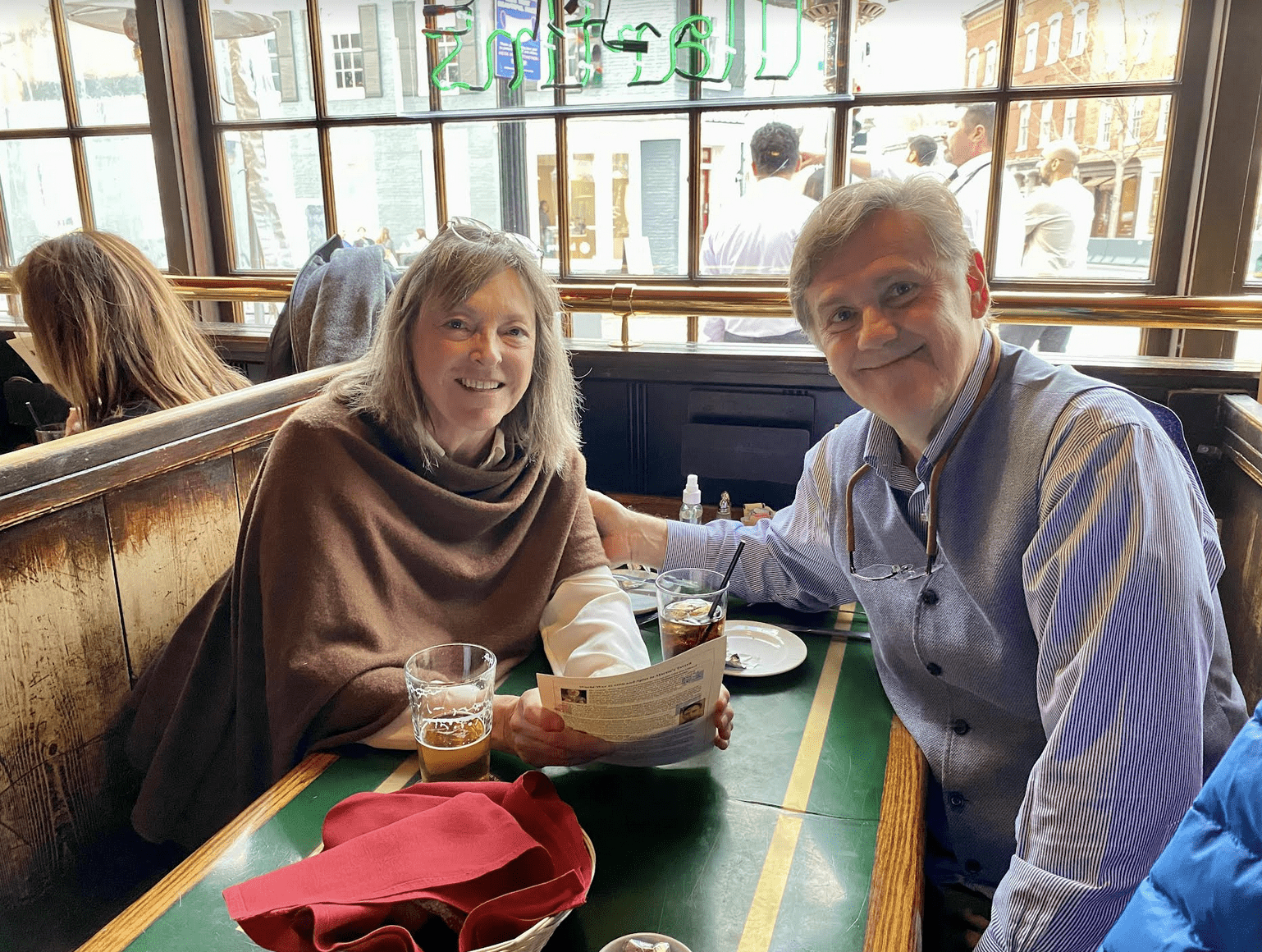

At historic Martin’s Tavern, where Jack proposed to Jackie

At historic Martin’s Tavern, where Jack proposed to Jackie

We tried our Maryland lump crab cakes at Martin’s Tavern in Georgetown, the oldest family-owned restaurant in Washington, founded in 1933 by former major league baseball player Billy Martin — the Boston Braves shortstop, not the hotheaded Yankees manager who came later. Every president since Harry Truman has eaten there, none more famously John F. Kennedy, who was a regular while he was a senator, and who proposed to Jacqueline Bouvier on Wednesday, June 24, 1953, in the wooden booth right beside the one where we were seated. Martin’s remains a hangout for media, politicos, spooks and anyone else who doesn’t want to expense a meeting or assignation at Café Milano or The Palm.

There are some things you can’t do in Washington as a Canadian. One is a tour the White House. Although Cheryl and I, as non-U.S. citizens, were able to tour the Capitol Building – including the current House and Senate chambers – the White House was a no-go area or us. It used to be that non-U.S. citizens could visit the White House through tours organized by their own embassies, in conjunction with the U.S. State Department. But that program was cancelled in 2011.

During our five days in Washington, Cheryl kept track of our movements on her Fitbit and discovered that in this walking city, we walked an average of more than 10 to 12 km a day. It was no wonder that our routine came to include a midday rest at our centrally located hotel, before venturing out once again into the evening. After dinner one night at a Thai restaurant on 14th St., we met a local man who complemented us on visiting Washington in February.

“This is a great walking city, but it’s too hot in the summer for walking,” he said.

We took the Metro — a lot. We each bought a transit card and put $15 into it at Reagan National, and then another $10 later, ending up with $2.50 left on our cards when we arrived back at Reagan National for our return flight home. The way things work, your card is debited when you use it to exit the Metro through a turnstile. You are charged an amount depending on how far you travel, and when you travel. On weekends, though, it is a flat $2 per trip, no matter where you go, no matter the hour.

Had we known about it, we would done more of our travelling on the DC Circulator bus network. DC Circulator buses, different from regular city buses, are like shuttle buses; they run between the city’s main attractions and some of the more popular neighbourhoods. There are six different routes – one of those is the route up and down the National Mall, which is a much longer and more tiring walk than it looks. Five other routes connect downtown and adjacent districts, including Georgetown, which is not accessible by Metro. The fare is $1 per ride.

At one point, Cheryl said visiting Washington feels like visiting the seat of the global American empire – akin to visiting Athens in 425 BC, or Rome in 70 AD.

That prompted a vision in my own mind of people 2,000 years from now visiting the ruins of 20th-and-21st-century Washington, like the Acropolis of Athens now. I saw these futuristic visitors putting on virtual reality goggles to get a sense of what the seat of the American empire looked like at its peak. True, amid the ongoing challenges to a democracy-led world order led by Washington, the US may now be portrayed as past its best before date. And yes, it was sad to see the ransacking of the Capitol.

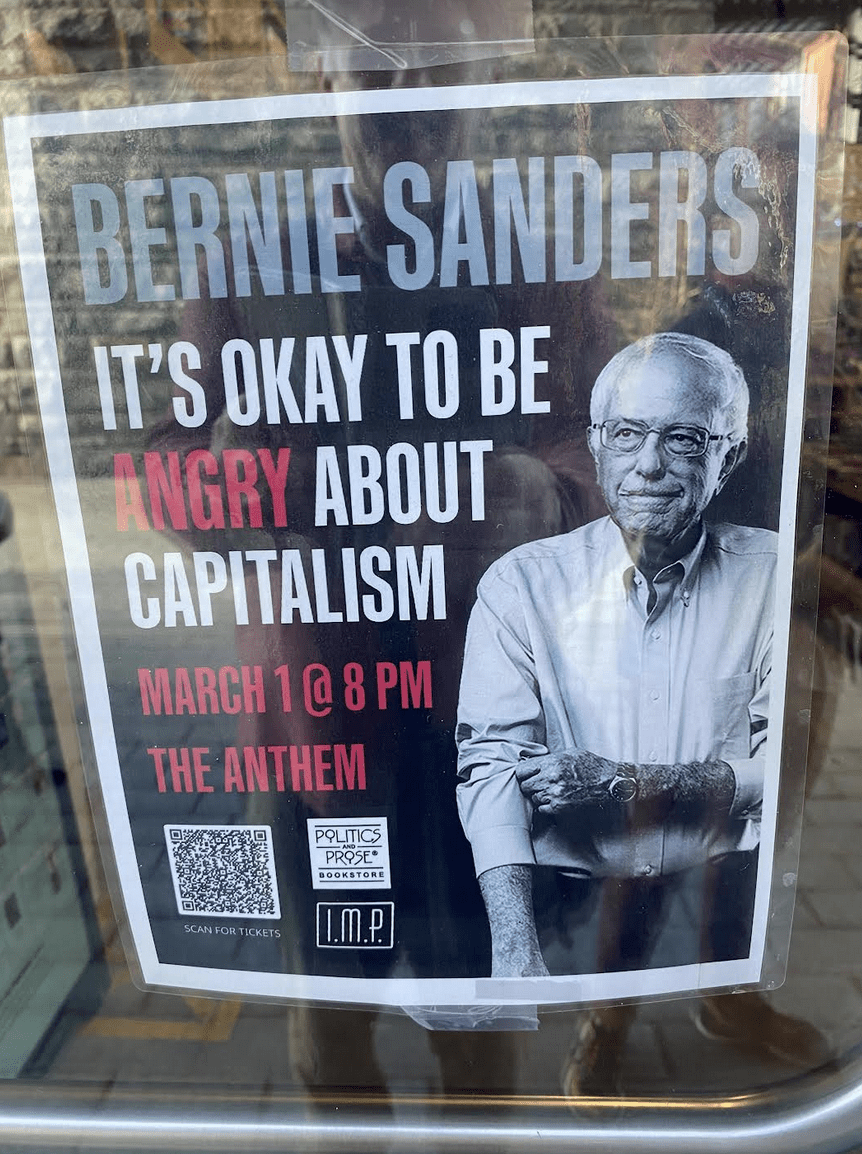

Another day in D.C.: Just missing Bernie

But we didn’t sense any sadness or defeatism in the city. The mood is very upbeat. The people are friendly. The monuments and the museums of Washington, and the auditoriums filled day and night with interesting speakers, reflect the great republic’s continuing vitality. We were just sorry we had to leave before Senator Bernie Sanders’s talk on his new book at the 3,000-seat Anthem auditorium in the Waterfront district on March 1. The title of his talk: It’s Okay to be Angry about Capitalism.

Policy Contributing Writer David O. Johnston served as Regional Representative in Quebec and Nunavut of the federal Commissioner of Official Languages from 2014 to July 2022. Previously, he worked at The Montreal Gazette for 33 years, concluding as editorial page editor.