Policy Dispatches: Witnessing the Indestructible Spirit of Ukraine

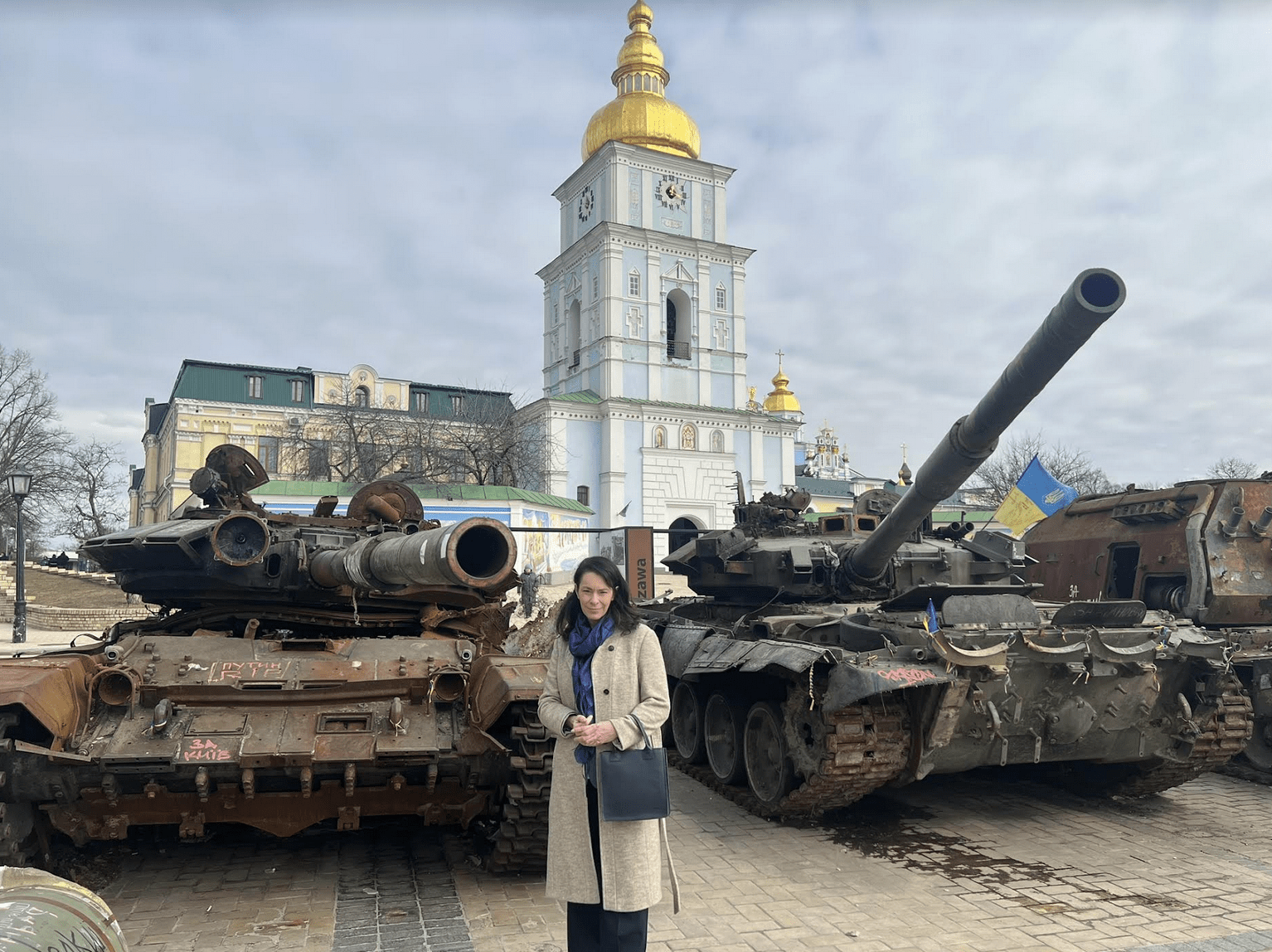

Visiting the war zone of Ukraine: seized Russian tanks on display at St. Michael’s Cathedral, Kyiv

Heather McPherson

March 13, 2023

Policy Dispatches are pieces combining travel, policy and political writing from Policy writers on the road.

Irpin is a suburban community just outside the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv — it reminds me of home and the small cities surrounding Edmonton. But Irpin’s tree-lined streets, grocery stores, bars, restaurants, playgrounds, and parks are now abandoned, blackened and riddled with bullet holes, their former occupants gone — murdered or fled.

Just three days after Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his illegal full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian forces, attacking from Belarus, laid siege to Irpin. The attack on Irpin and its neighbouring community of Bucha lasted a month. When it was finally over, evidence of the horrific massacre of civilians — of war crimes and crimes against humanity perpetrated by Russian forces — was revealed.

There were no military targets in Bucha or Irpin. Russia’s attacks were directed at civilians and civilian infrastructure, including hospitals, schools, homes, and apartment buildings.

I arrived in Irpin on March 3rd, exactly one year after the mass evacuation of the city. Some people were able to get out by train or bus, but most residents fled by car or on foot — women, children and the elderly, trying to escape the constant shelling, across the Irpin River to the relative safety of Kyiv. As they fled, Russian tanks and jets fired on them indiscriminately.

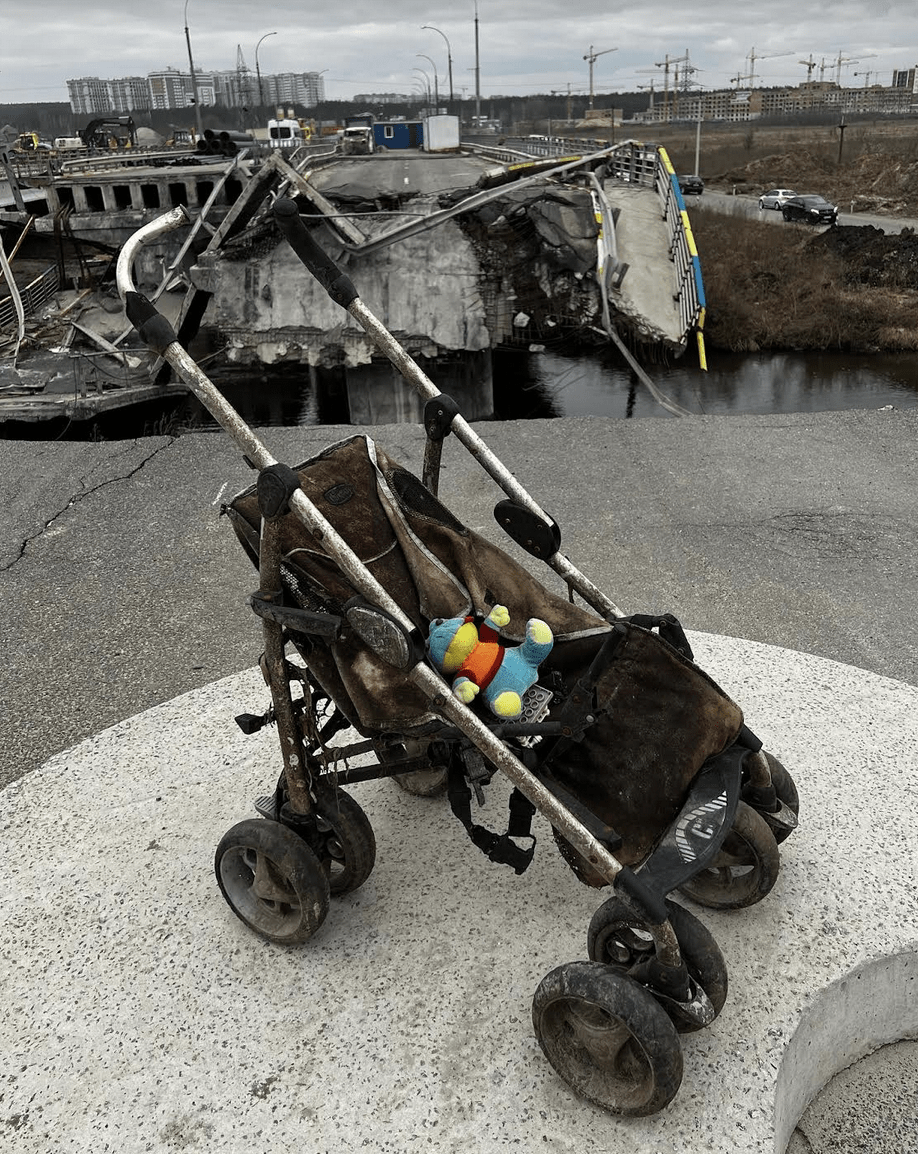

The destroyed bridge across the Irpin River is a landmark now, a symbol of the wanton terror that Putin’s war has inflicted on Ukrainians. I stood there, beside a stroller that sits atop the rubble, commemorating the baby girl and mother murdered there as they fled, thinking about my own family, my children.

Monument to a mother and baby killed in Irpin

This was not my first visit to a war zone. I spent more than two decades working in difficult and heartbreaking contexts around the world — in countries such as Mozambique, devastated by civil war and the ongoing curse of landmines; Uganda, where hundreds of thousands lost their lives to decades of war; and Nicaragua, where, even to this day, ordinary citizens endure the legacy of brutal regimes and foreign interference. In these and so many other countries, I’ve witnessed horrific suffering alongside the resiliency of the human spirit. In Ukraine, as in all war zones, the reality of violence, conflict and war that civilians — especially women, children and the elderly — suffer the most was starkly palpable. And, as in all war zones, the physical landscape and casualties serve as a testament to the pathology of the aggressor.

This was, however, my first time visiting a war zone as a Member of Parliament. I was not supposed to be in Ukraine.

As the Critic for Foreign Affairs and International Development for the New Democratic Party of Canada, I was in Europe, alongside MPs from the other parties who serve with me on the House of Commons Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development. The trip took us to Finland, Sweden, Belgium, and Poland as part of our study on Russia’s war on Ukraine.

The meetings with allies were enlightening, including discussions with Swedish and Finnish officials about their accession to NATO. In Poland, we made a pilgrimage to Treblinka, where close to one million Jews were murdered during the Second World War – a gut-wrenching reminder of the omnipresent machinery of evil. In a meeting with Ukrainian refugees, I shared letters and artwork sent by the students of St. Matthew’s School in Edmonton (a Ukrainian bilingual school) with the children.

Life, interrupted: Witnessing Russian destruction in Irpin

But the Foreign Affairs committee was not scheduled to go to Ukraine and this, I felt, was a mistake. How could we fully understand what was happening in Ukraine if we were not going there? So, I went alone.

I had been invited by Ukraine’s ambassador to Canada, Yuliya Kovaliv. Seventeen parliamentary delegations from 17 different countries had already visited. Among Ukraine’s key allies, only Canada had failed to send a delegation. So, while I could not represent the committee, I could represent Canada’s New Democrats and our commitment to the people of Ukraine, to their sovereignty, to their peace, and to their democracy.

For years, since Putin’s first invasion of Ukraine, New Democrats have sought visa-free travel for Ukrainians to allow those fleeing the invasions easier access to Canada. A year ago, I traveled to the Polish-Ukraine border to meet with Ukrainian refugees and learn more about their needs. New Democrats have demanded that our government give Ukrainian refugees the same federal support as other refugees, rather than placing them in limbo, forcing them to rely on charity for housing and basic needs.

Following that trip in March 2022, I developed a six-point plan for Canada’s response to the war, pulled from my years of experience working with humanitarian organizations in conflict zones. The plan outlined how Canada could provide humanitarian assistance, help protect women and girls from exploitation and abuse, support global food security, work with allies to document war crimes and support justice for victims, and assist in nuclear disarmament efforts.

I have sponsored three motions in the House, all of which were adopted unanimously: calling on the government to help document Russian war crimes and crimes against humanity; declaring that the Russian Federation is committing acts of genocide; and designating Russia’s Wagner Group as a terrorist entity.

I secured a special House debate on global food security in which New Democrats laid out the steps Canada should take to ensure that Putin’s attacks on Ukraine’s food infrastructure, designed to cause starvation in the Middle East and North Africa and trigger a subsequent migration crisis in Europe, would not be successful.

And in November, following a session I co-convened in Ottawa with international de-mining organizations, I outlined how Canada can work with allies and international organizations to help Ukraine clear their country from contamination by munitions.

Yet, much of my time and focus has been on Canada’s sanctions regime. Targeted Magnitsky-style sanctions against Putin and Russian oligarchs are a key tool to ending this war. Cutting off the money supply to Putin will save countless lives. But while our allies have successfully and transparently imposed sanctions on Russia, Canada’s sanctions regime urgently needs to be improved.

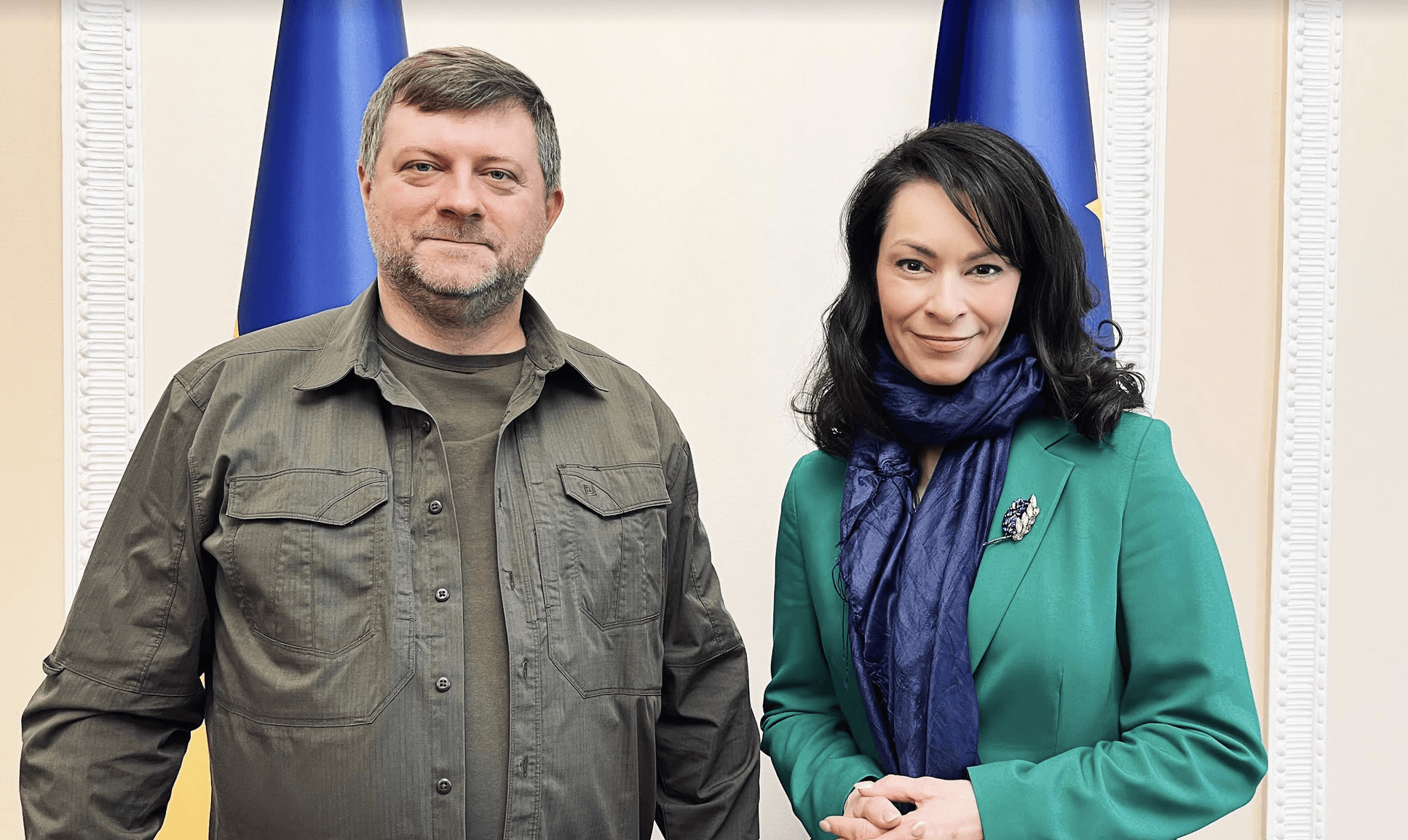

With Ukrainian parliament Deputy Chair Oleksand Kornienko in Kyiv

During my time in Kyiv and Irpin, I met with Oleksand Kornienko, First Deputy Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament) and Yulia Svyrydenko, First Vice Prime Minister. I also met with Members of Parliament, civil society organizations, community leaders and individual Ukrainians. They had one common message for Canadians, “We will continue to defend our country. We will continue to defend democracy, international law, and justice but we need real help, and we need it urgently.”

One year into this war, it is undeniable that Ukrainians are fighting for all of us.

Putin’s own words reveal his objectives — the destruction of Ukrainian independence, democracy, and identity and elimination of the perceived existential threat of western ideals of democratic freedom on his doorstep. Putin and his military leaders’ obsession with gay, trans, and women’s rights and their insistence that this war is about preserving “Russian family values” has earned supporters among the extreme right in Canada and around the world. He will not be satisfied until every Ukrainian is coerced into submission or is dead.

Russia’s targeting of civilians, use of illegal weapons, war crimes and crimes against humanity — including the use of rape and torture against civilians and children, kidnapping of children, attempts to weaponize food and starvation, and focus on erasing Ukrainian identity — all constitute genocide.

Our allies are united. In our meetings with parliamentarians from all parties in Poland, Sweden and Finland, we heard steadfast support for Ukraine. The countries closest to Russia know how vital it is to their future that Ukraine wins. Even if the world were not now so small as an incubator for evil, Canada shares an ocean border with Russia: our security, democracy, and humanity are also at stake in this war.

Over the coming weeks, the government will be forced to answer my call in committee for an improved sanctions regime. New Democrats will continue to push for support for Ukrainians coming to Canada, and for increased humanitarian aid and demining of the region. We will support rapid military aid and expedited work on nuclear disarmament. Our support is unwavering.

I am forever marked by the extraordinary courage and resiliency of the Ukrainians I met during this trip, and of all citizens of Ukraine.

Bombed-out cars in Irpin get a second life as an art installation

On my final day in Ukraine, as we walked through streets strewn with anti-tank obstacles, past burned-out homes and apartment buildings, Ukrainians emerged to greet me. One woman described the ongoing search for the missing — for their remains. A young man invited us back to his apartment for tea. Others showed us the pile of cars, abandoned by fleeing Ukrainians and destroyed by the invading Russians. Rather than haul them away, the people had left them, burned and riddled with bullet holes, as a monument to the battle for Irpin but now, painted defiantly with beautiful sunflowers.

Those cars perfectly capture the spirit of Ukrainians — a spirit that cannot be destroyed.

Heather McPherson is the New Democratic Party member of Parliament for Edmonton Strathcona. Prior to entering politics, she served as executive director of the Alberta Council on Global Cooperation.