Policy Q&A: A Conversation with Jean Charest

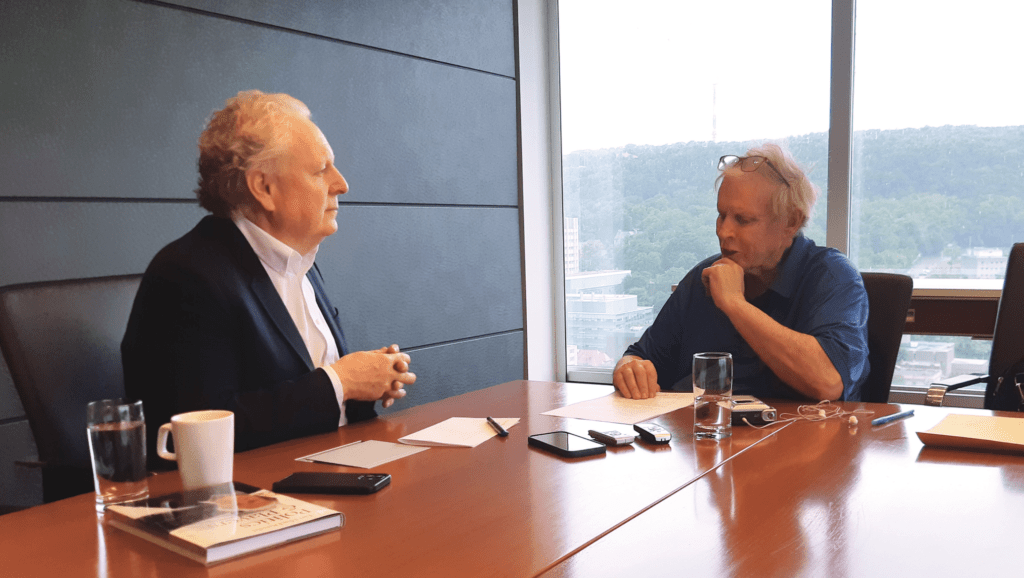

Ten years after he left active politics following nearly a decade as Liberal premier of Quebec, Jean Charest is a candidate for the leadership of the Conservative Party whose Progressive Conservative forerunner he led out of the wilderness during the 1990s. Policy Editor L. Ian MacDonald spoke with Charest in Montreal on June 16th.

Policy: Mr. Charest thank you for doing this and if we could begin the conversation with your reflections on Canadian unity. Beginning with the famous referendum speech of October 27, 1995. What was your sense of what was at stake that day? Because if 27,000 votes had gone the other way, is there any doubt in your mind that Mr. Parizeau would have declared in dependence the next day?

Jean Charest: I have no doubt in my mind that Jacques Parizeau would have declared independence in the 24 hours that would have followed the vote. That he would have pushed ahead because that was his style and his understanding of how this needed to get done. And just for the record to add to that, you may remember the famous interview that Jacques Chirac gave on CNN where, he’s the president of France, and actually confirmed that if the vote was in favour of separatism that Quebec would have the support of France. Which is one of the key elements in inter national law, public international law, for a country being recognized, is that other countries recognize the outcome of the referendum. So, what was at stake on that day was nothing less than the country. That’s what was on the table.

Policy: What was in your mind that day when you went to the podium? Did you discuss what you were going to say to with Michèle?

Jean Charest: Yes, well, I always had. Often, if I was delivering remarks or a speech, I would run it by her, and just give her a sense of what I was going to talk about. And then we had a meeting that was interesting at Place Ville Marie in the Leader of the Opposition’s office of Daniel Johnson. Mr. Johnson, Jean Chrétien and myself. We made our way down to the street level and over to Place du Canada and this huge crowd. I mean, it was the biggest crowd that I have ever spoken in front of.

Policy: One hundred thousand people.

Jean Charest: Yes, it was impressive, with a lot of emotion. I’d never experienced anything like it in my life.

There were several firsts in that week, by the way. On the Monday, there had been a rally in Verdun where, again, the emotion was running very, very high. And that was interesting because the emotional quotient of the campaign shifted. It was very much the separatists who had been running on a very emotional campaign. In the last 10 days of the campaign, the federalist side became very, very involved and the campaign shifted to this very tight race.

And the whole approach has been the wrong one and it sends a very, very negative message to those who are not francophones that they’re just not part of this discussion. The other thing that is obviously very disturbing is the wholesale use of the notwithstanding clause. Which I never used. I’m of the school who always believed that this was a measure of extreme exception that you only use in extreme circumstances .

Policy: Mr. Bouchard used to talk about the need for “winning conditions”, as he called them, before there would be another referendum. And in all the years since, the winning conditions have never been in place. Largely because even when you lost in 1998, I think you still won a plurality of the vote. Then, you won three elections in a row and even when you lost in 2012, the PQ was in a minority government and the winning conditions were not there.

Jean Charest: They never reappeared. The ’98 campaign is interesting in this way. It finally resolved the very tight outcome of the 1995 referendum. The outcome was so tight in ’95 that it was left unresolved. I say this we see all this in hindsight really, enough that Bouchard was promising a referendum. That was his plan and he publicly said “I am going to hold another referendum”. To this day the PQ apparatchiks and establishment have not forgiven him for not doing that, for not following through. But in that campaign of ’98, which went badly for me, it was all new and it was a very tough campaign. In the last 12 days, I made the decision and told my campaign team that we were running on one single message: No referendum. It’s the only thing that came out of my mouth for 12 days. We changed our communications. On election night, Lucien won a majority of the seats. We won a plurality of the votes. And the referendum died on that night. The idea of holding one. And finally, 1995 was resolved. Lucien Bouchard himself recognizes that, that his plan to hold a referendum died. What’s important about that moment is that’s what gave the country time to find its bearings and breathe and get back on track. And so, the most important election campaign in my lifetime was the one I lost.

Policy: And today, the PQ is not even a recognized party in the legislature and Premier François Legault is more of a Duplessis-style nationalist than a sovereignist or a separatist. Which brings us to one of the divisive questions that are in the news cycle as we speak. Bill 21 and Bill 96, as well as the Trudeau government’s Bill C-13 and the effect that those bills have or will have on minorities. Your thoughts on that.

Jean Charest: Let’s start with Bill 21 because it came to me in another form when I was premier. It was the Bouchard-Taylor Commission.

I almost lost the 2007 campaign on the issue of “reasonable accommodation”, which was a Supreme Court concept about how we accommodate minorities. Mario Dumont campaigned against that with great effect. And I put together the (Gérard) Bouchard-(Charles) Taylor Com mission to clear the air and have a conversation, a rational conversation, about it. They delivered a report in which they recommended outlawing religious symbols for people in authority. I refused to do it. I refused to do it because I didn’t believe it was right, but also the legal advice we were getting was that it was contrary to the Quebec Charter and the Canadian Charter. It would have been more popular for me to do it, but I didn’t do it because I felt it was wrong, and then it came back in the shape of Bill 21. And when it did, actually ironically, both Lucien Bouchard and I did a panel for the Quebec Bar where we were asked about it and both of us said that we were opposed to Bill 21, and I still am. And the whole approach has been the wrong one and it sends a very, very negative message to those who are not francophones that they’re just not part of this discussion. The other thing that is obviously very disturbing is the wholesale use of the notwithstanding clause. Which I never used. I’m of the school who always believed that this was a measure of extreme exception that you only use in extreme circumstances — that you don’t want to have to be on record as using it. So now we are in a world where it’s beginning to be a method of legislating that I find very disturbing. If that’s the case then we are going to have to have a larger debate about what this means for our laws and for our rights.

Policy: Of course, the feds have never invoked it.

Jean Charest: No.

Policy: It was the price of the deal for the first Mr. Trudeau and Alberta’s Premier Peter Lougheed and Premier Allan Blakeney in Saskatchewan and the provinces. So, it is historically legitimate but it wasn’t meant to be used so frequently.

Jean Charest: That’s exactly the approach, the notwithstanding clause is a measure of extreme exception, really extreme exception. Only to be used in extreme circumstances and for which it was designed in a way that there would be a political price extracted on the government that decided to use the notwithstanding clause. There would be an element of accountability on it. If you’re going to make it the mainstream method of legislating, well then you are in a different world. Let me just revert back to how we should treat the application of rights, which is lost in this debate and lost in Bill 21. Any effort made to restrain rights should be done with empirical evidence that there’s a reason to do it. If there is, it falls on the government and those doing that to make that case. To prove that there are reasons to do it. That’s what happened on language legislation in defending Bill 101. On the case of Bill 21 and Bill 96, that evidence was never produced.

We get old at one point, but living longer lives doesn’t mean we are older longer. We are healthier and in good form longer and then we get old, as we all do. So that’s good news, actually. The bad news is, our ability to adapt to that has been very poor and governments have not been doing their jobs in planning. For example, we now need to deal with the fact that we have labour shortages.

Policy: And the present Trudeau government’s Bill C-13, updating the Official Languages Act. What are your thoughts on that?

Jean Charest: Frankly, I find it confusing. Again, here’s an area where both the federal and provincial governments should be working together. There is a common reading or agreement that, yes, we need to protect the French language and culture in Quebec. We all agree on that. But what the government of Canada’s doing now is difficult to under stand. I mean, it’s difficult getting a reading of what exactly they’re trying to do and how they are going to accomplish it. And there are contradictions between the federal legislation and the Quebec legislation. I don’t have a problem, by the way, in saying that companies that are within federal jurisdiction should be applying language policies within Quebec that respect the language of the majority. By the way, it’s what they are doing. I know these companies and how they operate. It’s what they are doing in practice. But how you do it and how you conciliate that with minority rights is extremely important. You cannot legislate on this without being mindful of the minority rights of francophones outside Quebec and anglophones inside Quebec.

Policy: Let’s take a look back to the famous health care accord of September 2004 – the late-night pizza delivery deal at 24 Sussex – between the provinces, led by you, and Prime Minister Paul Martin; the $41 billion increase of health care funding over 10 years, indexed at 6 percent. Where are we today in terms of the aging population? Because, as you point out in your program for the leadership, 22 percent of the work force is now between the age of 55 and 64 and that sounds like a ticking time bomb in terms of the healthcare needs we’re going to have in long term care, and replacement of skilled people. Your thoughts?

Jean Charest: Well, this is something the governments have seen coming and to which they have not reacted, or done a lot on. A lot of it is very good news, if we just take a moment to look at why this is happening, it’s happening because we live longer lives. We live healthier lives. We get old at one point, but living longer lives doesn’t mean we are older longer. We are healthier and in good form longer and then we get old, as we all do. So that’s good news, actually. The bad news is, our ability to adapt to that has been very poor and governments have not been doing their jobs in planning. For example, we now need to deal with the fact that we have labour shortages.

There’s no reason why people who reach 62, 63, retiring if they are in very good health and want to continue. How do we adapt our labour markets to allow these individuals to continue to do what they want to do and not be punished financially because they continue to stay in the labour market? That’s the kind of forward thinking I want to bring to policies in the country, to the future of the country. On the health side, I think we are at an inflection point now. I would table a new Canada Health Act. I would untie the hands of the provinces, allow them to innovate. I would allow them to bring in private-sector delivery with a single payer. I would change that and I’d be very confident that Canadians would support that. You know our health care system was in bad shape before COVID. All the indicators were very low in terms of international comparisons. It’s been made worse by COVID, and now we’re at a point where Canadians are ready for a new approach.

Policy: Looking west…what are your thoughts on Mr. Kenney’s departure, the rise of Western populism and even separatism, and how Ottawa needs to deal with that?

Jean Charest: I don’t think Ottawa, Justin Trudeau is taking that seriously. I don’t think he has a real measure of the amount and the sentiment of discontent in the West of frustration and it comes with, first of all, the fact that in their period of difficulty they felt that they were not acknowledged or not recognized for what was happening to them and then the lack of reaction from Ottawa in terms of that. For example, they have always felt, rightfully so, that they’ve been a net contributor to the wealth of the country and that’s benefited every one. And yet when they get into trouble, it’s as though it doesn’t count. The other thing is the extraordinary efforts that have been made by the oil patch in the last few years to reduce carbon emissions….

Policy: Carbon capture and storage in Saskatchewan.

Jean Charest: Voilà.

Policy: And deals on the pipelines with First Nations on equity from Alberta to British Columbia that perhaps the energy industry doesn’t get enough credit for.

Jean Charest: It doesn’t, but it’s the job of the federal government to make that case to the rest of the country — that our fellow citizens in Alberta and these companies are making an effort and to defend them, so to speak. All that effort that went into the research, to the investment, all of it wasn’t recognized and that’s what has led to this high level of frustration. As leader of the Conservative Party, I would work from the base we have in the West. We are very proud of that. I want to work off that base to expand support to the whole country. To do that, we need to recognize the challenges facing Western Canada and respect its contribution to the country. And that’s the beginning point, I think, of a period of reconciliation that I would want for the whole country.

Policy: On the Emergencies Act and the convoy shut down of Ottawa and of the gateways to trade on the border. You said in your platform that you would end “illegal blockades”. There is a clear difference there from Mr. Poilievre, who during the Ottawa shutdown, had another view of the so-called truckers. You say you would make it a criminal offence and then pass what you call a Critical Structure Protection Act prohibiting the shut down of highways, pipelines, utilities, telecoms and railways. What about that?

Jean Charest: Well, one thing we’ve learned from the last two years is that if this country is going to deal with is sues, we need to do it in a way where we can have a conversation as opposed to just forcing shutdown of our economy. Shutting down our economy is not an option for anyone and it should not be. It hurts every single Canadian, it hurts businesses, and we should protect Canadians from that happening. That’s why I would bring in an Act that says if you’re going to do that, you’re going to be criminally responsible. I’ll give powers to the police, to the authorities to intervene immediately and not have to go to the courts for an injunction. And on the blockade in Ottawa, we clearly distinguish between the right to protest, the frustration that Canadians felt and the fatigue. All of that is there and I understand it and we see that and we share that. But where we draw the line is that no one is allowed to blockade and to do an illegal blockade. And in the case of Mr. Poilievre, it is unacceptable for any one who has made laws, makes laws, to contravene laws. You can’t be on both sides.

Policy: So, shutting down a city of a million people – a G7 capital – and the three branches of government for three weeks is not an option?

Jean Charest: And Mr. Trudeau, by the way, has a very real responsibility in this regard. How come this happened? I mean the whole unfolding of the event. I am sure you felt the same way. It was just unreal. We all sat there and we couldn’t believe this was our own country. And how could we go from one event to another? Mr. Trudeau fanned the flames. First of all, they allowed them on the Hill. Then he’s missing in action. I mean Justin Trudeau has a very real responsibility, and then the Emergencies Act. I voted on that Act in 1988 in the House of Commons to replace the War Measures Act. It never crossed our minds that this Act would be used to deal with a protest, an illegal blockade on Parliament Hill and now as we speak today the government just seems to be completely entwined in all sorts of confused explanation.

Policy: They can’t seem to get the story straight.

Jean Charest: No. It is not very reassuring and yet if you can’t get the story straight on invoking the Emergencies Act, there’s a problem. There is a real issue because this isn’t a simple Act of Parliament, this is the Emergencies Act, giving the Government of Canada extraordinary powers to do things because of an exceptional situation and you can’t explain why you actually did that? This is serious business. It’s very serious.

Policy: On defence, you propose finally achieving 2 percent of GDP, the NATO target. The last time we were there was under Mr. Mulroney. You’re talking about 100,000 men and women in uniform and up to 50,000 reservists. On equipment, we are still flying CF-18s 40 years later, ships are falling apart…getting to 2 percent seems to be much more than just a mathematical proposition.

If you can’t get the story straight on invoking the Emergencies Act, there’s a problem. There is a real issue because this isn’t a simple Act of Parliament, this is the Emergencies Act, giving the Government of Canada extraordinary powers to do things because of an exceptional situation and you can’t explain why you actually did that? This is serious business. It’s very serious.

Jean Charest: It is important to point out that reaching 2 percent is not going to happen as rapidly as we would like. Neither is it going to be simple. These are very important investments that are going to require some very careful planning. If you’re buying ships, as I want to do, I want to build armed ice breakers for the North and I want to build submarines that also have the ability to control the ice cap. I want to build two military bases in the Arctic. That for me is an urgent task for the country. And a national undertaking given the fact that our sovereignty is at stake and we have Russia as a neighbour. And to give it perspective, keep in mind that even the Americans do not recognize the Northwest passage as being Canadian and neither does Europe. (Former US Secretary of State) Mike Pompeo delivered a speech in 2019 in Finland at the Arctic Council in which he went out of his way in the speech to say that this is not Canadian territory. Even our closest allies are not aligned with us. So, this is an urgent task.

Policy: After Mr. Reagan had more or less conceded the proposition back in 1987 in talks with Mr. Mulroney.

Jean Charest: In a very astute com promise on that. Very astute. “Mulroneyesque” in that way because it accomplished goals of Canada with out embarrassing our ally, but allowed Canada to defend our core interests. Those were the days when we actually had a government on the international scene that defended our core interests and played a role, and that example speaks to the art of statecraft.

Policy: Would you have a conversation with President Joe Biden – given the supply management crisis in the energy industry because of the Russians – about Michigan and Line 5, and Keystone XL, which he canceled on his first day in office.

Jean Charest: There’s two issues I would raise with our American neighbours. They are not just neighbours, they’re friends and allies and we’re lucky to live next door to each other, no matter what the circumstances. We’re in a good neighbourhood and I just wish the Americans felt that way more spontaneously.

Policy: You grew up 20 minutes from the famous crossing, Stanstead, Quebec and Derby Line in Vermont.

Jean Charest: Yes, and I spent my summers on a lake where we boated into Vermont. When I was a kid of 10 years old, we would just go right into the State of Vermont and get off at the wharf, go to the store and come back.

Policy: Those were the days.

Jean Charest: Now, the conversation with President Biden would be about energy and frankly making the case that there is not a better ally, friend than Canada. Maybe they need to be reminded of the trade agreement of 1987-88 and NAFTA, that we actually guaranteed our American neighbours access to our energy resources when they were in crisis. I mean there isn’t a more real gesture of friendship and trust than that. And then I would extend that conversation to the automotive industry, which is shifting to electric cars, and supply chains and the protectionist tendencies of our American friends and just remind them that the cars run on batteries that have minerals that Canada has and if you want to have access to the minerals, we will have access to that supply chain and to that industry. It is a two-way street.

Policy: You’re saying in your platform that you would recognize Ukraine’s full territorial sovereignty, including Crimea, as part of the pre-2014 borders, and you would ship more weapons to the Zelensky government, including harpoon missiles and howitzers, and double the $500 million in aid, and fast track refugees. Is the government doing enough?

Jean Charest: Well, foreign policy is not an area of partisan policy. What I’m saying is that in the best tradition of who we are as a country, we should make every effort, all of the parties including the Prime Minister. It’s the Prime Minister’s job to reach out to the opposition parties on these issues. To make them part of the decision-making process as much as possible. Yes, we can disagree on Ukraine, and we should, in what it’s revealed is our difference toward our defence capacity and our inability to supply them with offensive weapons, which is what they need right now. And then there is the broader issue of their sovereignty. And here the Harper period is significant.

You’ll remember that Stephen Harper was one of the first world leaders to confront Putin directly in a public setting, about Crimea. It created a stir, and following in those footsteps, I think Canada needs to stand shoulder to shoulder with Ukraine. We should also anticipate the day when the country will need to respond to this. The Ukrainians are fighting a war for us. We should acknowledge that. This, their very courageous battle against Russia is also about our rights and our sovereignty and when the time comes to rebuild their country, they will need the world to help them do that. Canada should play a leadership role in making that happen.

Then I would extend that conversation to the automotive industry, which is shifting to electric cars, and supply chains and the protectionist tendencies of our American friends and just remind them that the cars run on batteries that have minerals that Canada has and if you want to have access to the minerals, we will have access to that supply chain and to that industry. It is a two-way street.

Policy: In terms of unifying the Conservative Party, seems to me that for all of their differences, one of the things that Mr. Mulroney and Mr. Harper agreed on was Ukraine. Because under Mulroney, Canada was the first country to recognize Ukraine’s independence from Russia back in 1991, when The Soviet Union was collapsing. Is there a point of commonality there between the centrist and right wings of the party?

Jean Charest: There is, and there is a broader issue for me that’s important to the success of government and governance and that is continuity. What makes a country’s strength is the ability of their leaders to offer continuity and stability in governance. The reverse side of that coin is that it is very destabilizing when a new government comes in and starts to undo everything the previous government tried to do. There should be a common line of thought that would give Canada credibility and strength in supporting Ukraine — as in the party with Mulroney and Harper on Ukraine — and give our voice significance on the world stage. That’s what we saw in apartheid, you know, from Diefenbaker, then to Pearson then to Mulroney. We underestimate the strength of continuity on those issues that gives a country credibility and strength.

Policy: On that theme of continuity, we are in June of 2022, marking the 30th anniversary of the Rio Earth Summit and I still remember the photos of you walking on the beach with Michèle and that summit marked the emergence of sustainable development and climate change as the global policy themes leading to where we are today. How do we move ahead on net zero and climate change and clean energy? Starting from Rio, when you were environment minister, because you’ve been there all along.

Jean Charest: Yes, it pains me that Conservatives have not been able to claim their legacy on this, which is a very, very powerful legacy. Clean energy.

Policy: It starts with acid rain.

Jean Charest: Yes, it does but the most successful environmental treaty in the world was the Montreal Protocol on CFCs and HCFCs. And then the Acid Rain Accord in 1991, the Clean Air Act in the US. Then there was Rio in 1992, where Canada played a leadership role. We are committed to zero emissions by 2050. By the way, the oil patch is committed to zero emissions by 2050. Then the question is, how do we get there and that is key because if we look around the world, Europe announced in January-February their policy, after Glasgow, and it includes using nuclear power and natural gas to get there. And that says something about the choices that we have here in Canada. We should be developing oil and gas in a smart way for this transition. We should have a comprehensive approach that includes carbon capture and storage, hydrogen whether blue or green, bio fuels, small modular reactors, which is a common project of four of our provinces Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario and New Brunswick. We need to also make the design right. I would do away with the Trudeau carbon tax on consumption, because that’s what it is and I would replace it with a levy on large emitters, which Alberta has been doing since 2002 and Quebec is doing with the carbon trading system with California.

Policy: And you say you would “remove the HST on carbon usage by EVs and tractors, energy star appliances and high-efficiency windows”.

Jean Charest: The idea here is to have a very comprehensive approach that recognizes that everything we do has an impact on the environment. There is no utopia. The real issue is what are all the things that we should be doing to mitigate that impact and taking HST off these products is one of the things we can do to encourage people to make the best choice.

Policy: And finally, your thoughts on the differences between centrist Conservatives, where you are coming from, and populist right-wingers, and bringing them all together after the 10th of September.

Jean Charest: There has to be unity. Like-minded people share common values. What are those common values? Fiscal conservatism, a market-based economy, economic policies that promote growth, including oil and gas pipelines. And respecting the rule of law is a very fundamental Conservative value. And finally, I’d say the one that is going to be central to our next national government is the way Conservatives practise federalism. It’s very different from the federal Liberals or NDP, respectful of the jurisdiction of the provinces. I close by saying, it could be a breath of fresh air to have in Ottawa a prime minister who has been a premier of a province, who understands how this federal system of government works and to actually be out there implementing a Conservative agenda for the country.

Jean Charest, a current candidate for the Conservative leadership, is a former federal cabinet minister, and three-term former premier of Quebec.

L. Ian MacDonald is editor and publisher of Policy Magazine.