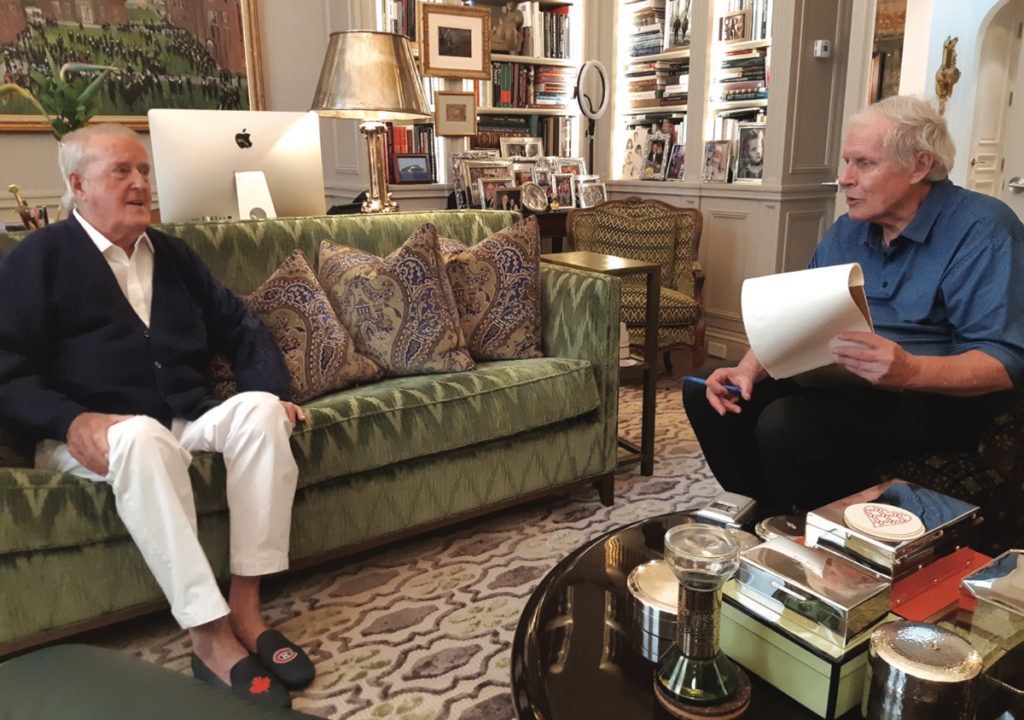

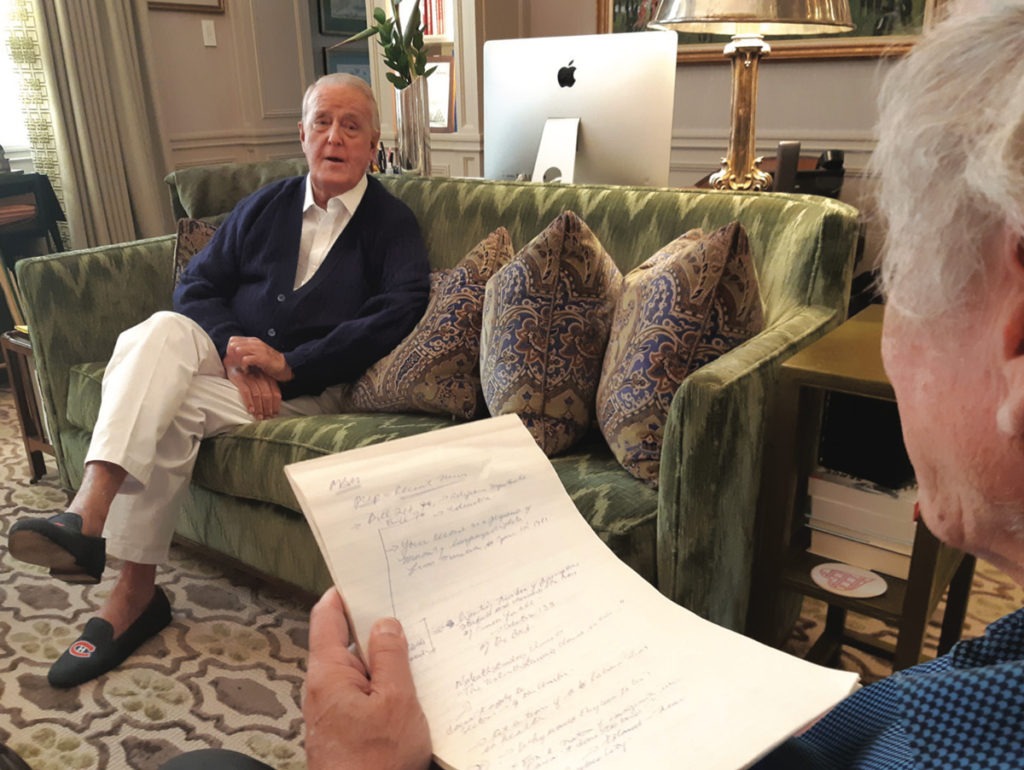

Policy Q&A: Brian Mulroney on Free Trade, Minority Rights and ‘Ain’t Life Grand?’

When Brian Mulroney became prime minister in September of 1984 with the largest mandate in Canadian history, a bilateral free trade deal with the United States was not on his agenda. From his speech to the Economic Club of New York in December, 1984, to the Shamrock Summit with President Ronald Reagan in March 1985, to the release of the report, a year after his election, of the Macdonald Commission on the Canadian economy advocating bilateral free trade, the momentum for a deal that would change both Canada’s economy and its national character intensified. More than three decades after Canada-US free trade became a reality, Policy Editor L. Ian MacDonald spoke with the prime minister who, in 1988, staked his government on a vision and won. This Policy Q&A was conducted at the Mulroneys’ home in Montreal on August 16th.

L. Ian MacDonald: Mr. Mulroney, thank you for doing this.

Brian Mulroney: Happy to be with you.

Policy: The theme of this issue of Policy, as you know, is Free Trade: Then and Now. What’s your sense of the then and now, in general terms?

Brian Mulroney: Generally speaking, you have to wait 30 or 40 years before you’re able to evaluate important policy change in Canada. See, once it works through the system, what the results are. Jeffrey Simpson used to say that durability is one of the most essential components of successful public policy. Is it still there 30, 40 years later?

Well, in terms of free trade and NAFTA it’s very much there. And the hostility or skepticism about it has transformed into strong popular support. That’s because the results have been so positive for Canada.

There’s a second element to it. The economic success has been quite striking. But also, there has been a transformation in thinking. [Former Privy Council clerk] Kevin Lynch wrote that the most important part, in his judgment, of free trade and NAFTA was the manner in which it transformed the thinking of Canadians…the attitudes of Canadians. He said we are not fearful or timorous of the United States. And that’s what it did — there was a profound attitudinal change in Canada. So, I think those are the two main benefits.

Policy: Well, it’s interesting in the Abacus poll that has been done for this issue, they found that support for free trade now is 52 percent in favour, 7 percent opposed, 30 percent undecided or won’t say, compared to the start of the free trade election in 1988, 38 percent in favor, 42 percent opposed, and 10 percent neither/nor. Those are pretty significant numbers.

Brian Mulroney: Yes, they are. You know, as Jeffrey Simpson also said, durability counts, and here we are 35 years later. And if someone ran on the policy program today of eliminating free trade or NAFTA, he wouldn’t get out of the starting gate. It’s part of our psyche now. It’s part of our DNA because Canadians have enjoyed the prosperity and the benefits.

Policy: And one of the attitudinal questions was: “Has it been good for Canada?” Thirty-two percent yes, 16 percent no. And on whether it has been good for the relationship. 44 percent yes, 17 percent no. On whether we got a better deal at the bargaining table than the Americans, Canadians are reluctant to believe that we could outsmart the Americans.

Brian Mulroney: Well, I don’t blame them.

Policy: That probably doesn’t surprise you. On the make-or-break moments of the FTA and NAFTA, I want to look back to the evening of October 3rd, 1987 on Saturday night at the Langevin Building, as it was then called, on the third floor, at your office, with Ronald Reagan’s “fast track” authority for a negotiated deal to be voted up or down without amendment by Congress, expiring at midnight and you were insisting on a dispute settlement mechanism so that it wouldn’t end up in American courts.

Brian Mulroney: Exactly, and so we wouldn’t lose our shirts.

Policy: And James Baker called and said that having consulted the leadership of Congress, who were there with him, it just couldn’t be done and you said, it was a deal breaker for Canada, and you said you were going to be calling President Reagan at Camp David to tell him…?

Brian Mulroney: Well, what happened was, I said, “Jim, fine, you know this has been a deal breaker for us from the beginning and so I’m going to call President Reagan now at Camp David and I have one question for him. The question is ‘why do think it is that the United States can do a nuclear weapons reduction treaty with it’s worst enemy, the Soviet Union, but you can’t do a free trade deal with your best friends, the Canadians?’” And Baker said: “Give me 20 minutes.” And then, the story shifts back to Washington. Twenty minutes or so later, Baker walked into the boardroom at the Treasury building next to the White House, which held eight Canadian negotiators.

And he threw a piece of handwritten paper on the desk, and he said to the Canadians: “There’s your goddamn dispute settlement mechanism. Now, can we get this thing up to the Capitol before fast track expires at midnight?” That’s what happened.

Policy: Leaving Langevin building at 1:30 in the morning Sunday you met the reporters at the bottom of the stairs and said, in words that may be inscribed somewhere some day: “One hundred years from now, what will be remembered was that it was done. The naysayers will be forgotten.” Would you take that as an epitaph?

Brian Mulroney: Any day, I don’t want to go anywhere, but I’ll take it any day.

Policy: Well, 35 years later, support for free trade is bipartisan and overwhelming on both sides of the border. Let’s discuss the numbers on Canadians thinking the Americans got the better of the deal. You’ve said privately that you don’t find that remarkable because there’s not an election going on now, it’s not competitive,

Brian Mulroney: I will give you an idea of the profound change.

When it appeared that Donald Trump’s administration might put an end to NAFTA, all of a sudden, the seriousness of this dawned on everybody, including the Liberal government, most of whose members had opposed it. But by this time, the realization was that “Hey, this is one of the backbones of the Canadian economy. If we lose this privileged access there are jobs at stake here.” And that’s when Mr. Trudeau called me and Derek Burney and I visited with the cabinet. First time in history, a former prime minister of one party met with the cabinet of another to discuss free trade negotiations and why it was vital that they succeed. And Justin Trudeau, the prime minister, and the minister of international trade at the time, Chrystia Freeland and Trudeau’s principal secretary, Gerry Butts, they were, I would say, the important trio. And when I was asked by the media coming out of that cabinet meeting in 2017, “What’s going on here?”, I said, “There’s no Conservative or Liberal way to negotiate a free trade agreement. There’s only a Canadian way.” And that’s why there’s no partisanship in this at all. I acted as an adviser to them pro bono for two years and it succeeded. And I think it’s one of the significant achievements of the Trudeau government.

Policy: Five years ago, in an interview with us, with Policy, you said about that moment in history — the ’88 election in particular: “Had we lost that election and the Free Trade Agreement, there would have been no free trade, there would have been no NAFTA, there would have been no GST and then where would we be today without all of those things? So it was a very consequential time.”

Brian Mulroney: It was. You know, it takes time to be able to appreciate that because the results are now in.

Policy: One of the things you got from Ronald Reagan, the former president of the Screen Actors Guild, was the cultural exemption for Canadian radio, television and film.

Brian Mulroney: That’s right.

Policy: How did you get him to go along with that?

Brian Mulroney: Well, we used to chat about it in all of our fairly regular meetings. I used to say to him, “Ron, you want protection for California wines I want protection for our artistic colony. So why don’t we cut a deal on this, our negotiators can deal with the other big stuff. But this is important to you and it happens to be very important to me.”

That led to the cultural exemption.

Policy: Going forward to the next presidency, of your friend, George H.W. Bush. In the beginning, the Americans were going to have a bilateral deal with the Mexicans that we weren’t involved in.

Brian Mulroney: When I heard about this, I called him and asked what was going on? We arranged to have lunch and I went down to the Oval Office. Bush told me Carla Hills, his USTR (US Trade Representative) recommended strongly to him and to cabinet that the United States negotiate free trade separately with Mexico. I said, “George, this doesn’t make any sense because we already have a free trade agreement with the United States. You would enter into a separate negotiation and agree to provisions that are going to dilute achievements in our agreement, for which I’ve paid in blood, as you know, in Canada. I had to fight a goddamn election to get this thing through and there were all kinds of attacks, misunderstandings and brutality in that election.” In fact, people refer to it, historians refer to it, as the most important, most challenging election in the history of Canada. Don’t know if that’s true or not but people have written books on it. I said “And you’re going to go ahead and sign a deal with Mexico without me?”

And he said, “Brian, that’s Carla Hills’ recommendation.” I responded: “I know Carla well. I love Carla, she’s a great person.” But I said to him, “George, I don’t give a good goddamn about Carla’s opinion. I am concerned about your opinion. And I’m telling you right now. This is a litmus test of our relationship, of our situation, and I’m going to view this as a hostile act.”

And so Bush said, just before we went out to lunch, he said, “All right, Brian let’s call it a day and I’m going to be back to you on this.” About three days later, I got a call from Baker, who was then secretary of state and Baker says, “The President asked me to look into this and we agreed that this should be a trilateral negotiation.”

Policy: Leading to the trilateral talks beginning in February 1991 and culminating in the initialling of NAFTA on October 7th, 1992.

Brian Mulroney: That’s right, exactly.

Policy: And today, Canada’s imports and exports from the US compared with 1985 as a percentage of GDP I think about 60 then…

Brian Mulroney: It’s 75 percent now.

Policy: And very much in balance, as you’ve pointed out, when services are included. As you once said, Americans tend to set aside services when talking about these numbers.

Brian Mulroney: The numbers that I have anyway, they’re very important. By 2019, the US represented over 75 percent of our exports, and Canada represented 18-20 percent of theirs. Canadian exports have increased 187 percent since 1993, while US exports to Canada climbed 191 percent. Now this is very important because of the concept of free but fair trade, right? Look at how free and fair this was. Canada’s GDP, in Canadian dollars, increased from $724 billion in 1989 to $2.23 trillion in 2019. This means that while Canada’s population in those 30 years grew from 27 million to approximately 38 million, an increase of 40 percent, our GDP increased by 207 percent. So, what it means is really that while it had taken Canada roughly 125 years to achieve a GDP in the neighborhood of $800 billion, under free trade and NAFTA it took just 25 years to triple it. Astonishing.

Policy: In environmental terms, there’s a serious disagreement with the US over pipelines. Keystone XL, which Mr. Biden cancelled on Day One in office and Enbridge Line 5, to which Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer has objections. And at this very moment because of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, there’s a serious supply management issue of petroleum in Europe. Your thoughts on that?

Brian Mulroney: It’s been a bit of a mantra with me, as you know, I’ve always contended there’s two important files on the Prime Minister’s desk. One is national unity and the other is Canada-US relations and if you take your eye off the ball on Canada-US relations, or if you let it get away from you, or if it does not become your number one objective, you’re going to pay a price and this is the price that we are paying.

Policy: And looking at CETA, the Canada-Europe Trade Agreement and the ongoing Trans-Pacific dialogue, on the mindset of Canadians, how it’s changed with free trade. You used to say that it would make Canadians more confident of our ability to be world competitive.

Brian Mulroney: Kevin Lynch wrote that free trade helped Canada to grow up, turn its face out to the world to embrace its future as a trading nation, to get over its chronic sense of inferiority. Free trade got Canadians to believe in ourselves, to take down the tariff barriers and think we could compete with the world’s largest and most competitive economy and do well at it. All of these things were made possible by thinking about the world through a totally different prism and free trade allowed us to do that.

Policy: NAFTA 2.0, is now subject to a “joint review” six years after coming into force. Is this an acceptable provision?

Brian Mulroney: That’s the price that Mexico and Canada paid to indulge Trump and his constituents that this was not a forever deal and if he wasn’t satisfied with it, he’d break it up. But I find it was an acceptable arrangement for Canada to make to preserve the integrity of the agreement.

Policy: Biden, as you know, has recently agreed that mineral supplies and so on will qualify under rules of origin of parts included in 75 percent North American content, especially in electronic vehicles. Your thoughts on that.

Brian Mulroney: Well, in that, I think the federal government did a very good job, as did the Premier of Ontario. That’s where all of the automotive factories are located and Doug Ford and Chrystia Freeland developed a very good relationship, and they worked together very closely on this. And Ford worked very closely with the neighbouring states’ governors, all of whom shared the desire to have this amendment. And so, I think that the Canadian government and the government of Ontario ought to take a bow on this one.

Policy: Turning to other issues: Russia and Ukraine. As you know, the end of the Cold War began with Reagan’s famous words at the Berlin Wall. “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” And you became, even as the Soviet empire was collapsing in December of 1991, the leader of the first country to recognize an independent Ukraine. Given the state of things today, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, do you think Mr. Gorbachev felt vindicated?

Brian Mulroney: Well, it runs counter to everything he fought for.

He sought modernization of the Russian economy and the acceptance of him as a leader of the Soviet Union as a major player — a constructive player — on the world scene. I witnessed his action, for example in the first Gulf War, where they could have killed it off with the veto at the UN. But they went along with the unanimous verdict of the Security Council. He became a celebrated figure on the world scene. Highly influential. He wanted that to continue for Russia. And in a certain way, Boris Yeltsin continued that. You know, he was pro-business, pro-internationalism, he joined the G7 and it became the G8. He was also very much in the Gorbachev mould. The present occupant of the Kremlin has not turned out to be in the same mould.

Policy: More in the Czarist tradition.

Brian Mulroney: He yearns for the good old days, he yearns for the resurrection of a Russian Empire where you would have one language, one religion, one system of government and one leader, him. And that’s why the occupation of Ukraine took place. Very authoritative sources have told me that he really thought that he’d be in and out of there within three days, installing a puppet regime, and then move on to other parts of the restoration of the Russian Empire — the Baltic states and so on.

Policy: To Canada now. You are known as a champion of minority rights and minority language rights from the time of your maiden address in the House in September of 1983 on French language rights in Manitoba. I wonder what your thoughts are about the current political context in Canada, with Quebec’s Bill 21 since 2019 and now Bill 96 with their restrictions on dress and access to English language post-secondary education.

Brian Mulroney: I’m opposed to any kind of discrimination at any time involving any people in Canada. Discrimination is just wrong. I don’t favour it. But, you know, how did this come about? It came about because of the insertion into the Canadian Constitution of the notwithstanding clause, which constituted a monumental giveaway to the provinces.

The weakening of Canadian constitutional rights was not evident during the patriation of the Constitution in the early 1980s. The obsession with patriation of the Constitution threw everything, including most fundamental rights and freedoms, out the window and gave the provinces and the federal government a lethal new weapon called the notwithstanding clause. Tom Axworthy has recounted the following: In April 1982 at the celebration with the Queen, before the signing of the new Constitution, Pierre Trudeau saw his old friend and intellectual patron, Frank Scott. Trudeau said to the Queen, “Madam, if we have a Charter of Rights in this country, we owe it to this one man. Everything I’ve learned about the Constitution. I’ve learned from this man.”

But Frank Scott felt that too much and been given away with the notwithstanding clause, and as Scott retold the story, he would end with the disclaimer that Trudeau “didn’t learn enough.” So, there it is, 40 years on, the trouble with Trudeau and the notwithstanding clause. His apologists make the argument that he had disdain for the clause and that he only agreed to do it under duress. He believed that the Charter with the notwithstanding clause was better than no Charter at all — that it was a quote, unquote, “Convenient pacifier for the provinces.” I stand by my position, expressed in the House of Commons in April of 1989. It kind of defines where I am on this, from the time, as a young attorney, when 29 professors, associate professors and teachers’ assistants, were arbitrarily terminated in the faculty purge of Loyola College and I got them all reinstated. My intervention as Prime Minister on behalf of David Milgard. My action to free Nelson Mandela from his prison cell on Robben Island to help dismantle the system of apartheid, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the commission of inquiry into Nazi war criminals in Canada, or on the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War Two. I’ve always had an affinity for the bullied or the underdog, a trait I inherited from my father.

Trudeau’s biographer, John English, wrote that Mr. Trudeau, in his final words in the House, said that we cannot erase the past, we can only be just in our own time. Thus, he concluded the Charter of Canadian Rights and Freedoms was created in the present to prevent the past wrongs for the future. However, as the renowned constitutional scholar Eugene Forsey, who was appointed to the Senate by Prime Minister Trudeau, correctly concluded, the inclusion of the notwithstanding clause in the Charter relegated that promise to little more than a mirage. The notwithstanding clause is a dagger pointed at the heart of our fundamental freedoms and should be abolished, Forsey declared. In his most telling indictment, he reached back to that dark episode of our past, he concluded the Charter would not have protected the Japanese Canadians who were forcibly interned during World War Two. So that’s where I was.

Policy: And in terms of the override of this clause, which has been invoked by Quebec on Bills 21 and 96, it also overrides, as every grade 10 student in Canadian history remembers, the basic division of powers of Articles 91 and 92 of the British North America Act, and then section 133 on the confessional rights of minority languages in Quebec.

Brian Mulroney: When this matter emerged, in Quebec, I agreed with the position taken by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the time that this will be sorted out in the courts. We have an excellent Canadian judiciary, excellent. Non-partisan, once appointed the judges really do the Lord’s work, with impartiality and skill and integrity, I found that out myself. And they’ve started to do their work. The Quebec court recently suspended two provisions of Bill 21, and by the time this reaches the Supreme Court of Canada, it’s going to be a different kettle of fish.

Policy: On Indigenous peoples, in your 2020 article for the Globe and Mail series, Big Ideas, you singled out Indigenous issues as Canada’s top priority, calling for, as you wrote, full Indigenous justice and implementation of the Erasmus-Dussault report on the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, which you appointed in 1991, but whose 1996 recommendations have been ignored by four successive governments in the quarter century since then.

Brian Mulroney: A fundamental challenge that we face — morally, legally and rationally — in Canada is the blight on our citizenship of the treatment of Indigenous People since time immemorial, and the solutions to this are to be found in the Erasmus-Dussault report. For example, let’s take the practical. We have, I think, it’s 175 billion barrels of oil, in Alberta, untouched. How do you get that out of the ground into a situation where you help the rest of the world and ourselves and you generate trillions of dollars of revenue for Canada, which helps our people and which solidifies our sovereignty? How do you do that? You do that by building pipelines. It’s the only way out. How are you going to build pipelines if our native communities’ land claims have not been properly settled? They’re going to obstruct any development along with the environmentalists. So, you’re paralyzed unless you deal with these things. It is a matter of not only national security and sovereignty. It is a matter of practicality. These matters of Indigenous injustice have to be dealt with on a priority basis and how do you deal with them? You deal with them in one way — with leadership.

Somebody, usually the prime minister, has to say, here’s the solution.

You bring the premiers in, the producing provinces, Indigenous leaders, the environmentalists, stakeholders and say here’s a solution whereby we generously solve this matter in the interest of all Canadians, we all have to put water in our wine, but here’s a generous and fair solution.

Go home and think about it for a month and come back and let’s see. And if it is accepted, fine, that’s terrific, and if not, the prime minister, if it is important to him, as it should be, then says, “I’m going to have the Canadian people decide this in the general election. It’s that important, so that’s the way I think that has to be handled.”

Policy: Speaking of Indigenous issues, I wanted to ask you about Nunavut becoming a territory, and whether that was an issue with the Northwest Territories, and how did you get the idea?

Brian Mulroney: It was just in the normal course of events over 10 years, I just thought that it made no sense to have the Inuit in Nunavut to have to travel 3,000 miles to some other part of the Northwest Territories. And I thought that was crazy. Tom Siddon was the minister, an excellent minister throughout. And we thought if ever the Inuit are going to have their own parliament, which I thought they should, we would have to divide the territory. That’s how it happened. It just evolved, and the more we thought about it, the more sense it made. So, we pushed that through before I left. And I went up to Nunavut before I left and we had meetings up there at which I announced the decision to make Nunavut a territory. That’s how that happened, and Tom Siddon was a hero in this thing. In constitutional terms, we could do that. And secondly, the entrenchment in the Constitution of Richard Hatfield’s old Bill 88, making New Brunswick Canada’s only officially bilingual province, and we did that as an agreement between the two governments.

Policy: Canada is a nation of immigrants. You used to say that “for a nation of immigrants, we haven’t done too bad” and you talked about that once in a speech about Grosse-Isle, the island just east of Quebec City that was a quarantine station for generations of Irish immigrants. Today we are faced with a shortage of skilled labour, for example in health care. And you wrote in your 2020 piece for the Globe that Canada needed to open the doors to immigration and grow to nearly 75 million people, nearly doubling our population. In essence, to become a nation of immigrants again.

Brian Mulroney: This is a no-brainer. We only have 38 million people.

Second-largest landmass in the world after Russia and we need immigrants. By the way, it’s a highly competitive world out there for immigrants. When I came in, I think Canada was taking in 80,000 immigrants a year. By the time I left it was 250,000, the largest number in history, with many more refugees added to that. But while that was a top number, it remained so for many, many years after I left. Recently, the Government of Canada has taken some dramatic steps. Sean Fraser, the member for Central Nova, is minister of immigration. He’s been doing a great job articulating a vision for Canadian immigration, indicating they are going to go from somewhere around 325,000 to 450,000 on their way to 600,000. This is a major departure from every Canadian government since mine and it seems to be going pretty well. The other provision, of course, is that we have to change our thinking in respect of Canadian families. Young Canadian couples trying to start families have to be encouraged through the use of child care and tax benefits. We are only going to expand our population in two ways — immigration and birth rates. Imagine the influence we would have internationally if we had 75 million people, or 100 million people, which we should have eventually. Our American competitors are growing, they are at 330 million people now. We have to try and compete with them in population growth as well.

Policy: Climate change goes back with you to acid rain in the 1980s, and then forward to the Rio Conference of 1992, where you were one of the advocates of sustainable development and climate change being put on the global agenda. Your thoughts on where we are now — on the global urgency of climate change going forward.

Brian Mulroney: It’s the number one issue for any prime minister or president and if that’s not recognized and accepted, then this government and all of us have a big problem. There are still climate deniers everywhere, and they have different positions of influence. But the numbers and the realities are eroding their positions on a daily basis. There are fewer and fewer of them. You know, I think of the fight we had to put up just to get an acid rain treaty. And then do the Montreal Protocol on the ozone layer in 1987. As it turned out. The United Nations said the Montreal Protocol was the greatest international treaty ever achieved.

Policy: According to the UN: “the only UN treaty that has been ratified by every country on earth — all 198 member states.”

Brian Mulroney: We need the same thing on climate change. We need the same profound attitudinal change and concurrent government actions. But also, most importantly, we need leadership.

Policy: Now to close, the Emergencies Act. You passed the Emergencies Act in the summer sitting of 1988 to replace the War Measures Act and requiring what you called “the concurrence” of Parliament, which had not been necessary when the War Measures Act was invoked in the October crisis of 1970. It was invoked for the first time in February to free Ottawa from the blockades that shut down the capital for three weeks and, it did obtain concurrence and the House approved it within the seven days as required, and so did the Senate. Do you agree that it was justified in invoking the Emergencies Act?

Brian Mulroney: Well, in fairness I wasn’t there. I was out of the country during that time. I got what little information I could.

My inclination would have been to negotiate this thing. To have the truckers into my office. Or we could have had Don Mazankowski have them in and give them a message: Look, you are after four things here. The first two make sense, we can do something there. The last two are out of our reach. Have the cameras come in, and I’m going to take pictures of you doing this and I’m going to give you the first two things on your list. Because they are doable. The first one I remember, I think anyway, was the truckers returning from the United States. Yeah, that we can do for you. What are you going to do for me? You’re going to go home. You got what you came for. Here it is. Let’s celebrate that. You made your point. But if you hang around here, disrupting an entire city for weeks and weeks, there will be consequences.

Policy: How do you feel at 83, with four successful children, 15 grandchildren, a very successful marriage to Mila Pivnicki Mulroney? How do you feel about life in general?

Brian Mulroney: Ain’t life grand? Life is grand. I mean we’re having the time of our lives. It’s fantastic. I enjoy it. We spend a lot of time with the children, of course with the grandchildren. In fact, three of them just left, they spent with the week with us here. They just left the other day.

And I spend time at the Mulroney Institute down in Antigonish. And Laval. I work with some of the charities in town. I work at the law firm. So, I’m a very happy guy.