Policy Q&A: Sen. Peter Boehm on ‘Pull-Asides’, ‘Bump-Intos’ and the Rome G20

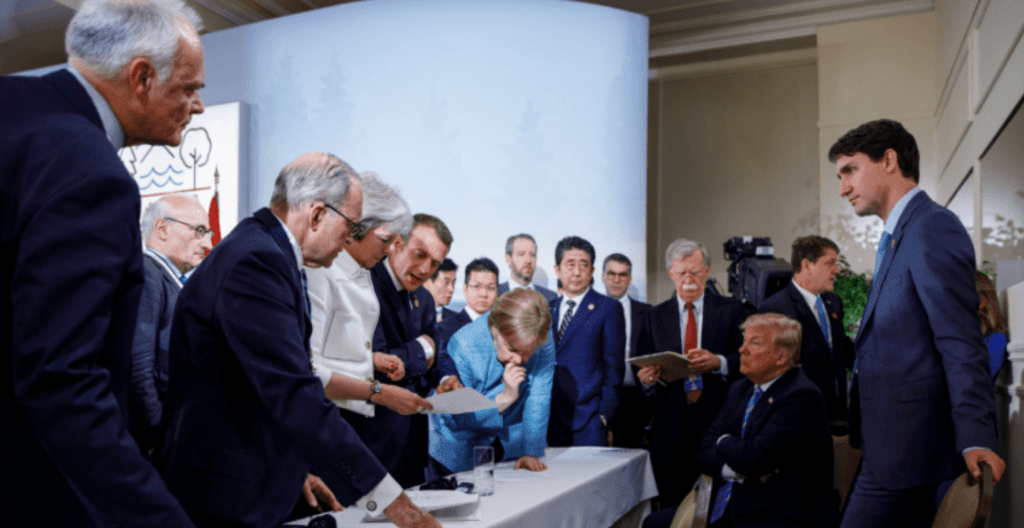

Peter Boehm, far left, in his role as Canadian Sherpa at the 2018 Charlevoix G7/Adam Scotti

The G20 will be meeting in Rome on October 30-31 with COVID, climate change and economic recovery preoccupying the global policy agenda amid increasing geopolitical tension between liberal democracies and China. During his career as an ambassador and deputy minister, Senator Peter Boehm served as Canada’s Sherpa for six G7 Summits. Policy Associate Editor Lisa Van Dusen conducted this Q&A with Senator Boehm by email ahead of the Rome G20.

October 27, 2021

Lisa Van Dusen: This G20 comes more than a decade after the group’s high point of cohesion and effectiveness, the London G20 in 2009 at which the remedial measures to address the global financial meltdown were adopted. How would you compare the G20 of 2009 to the G20 of 2021?

Sen. Peter Boehm: The G20 was originally a Canadian idea championed by former Prime Minister Paul Martin. He saw the value of the summit as being primarily for economic policy deliberation and initiatives, which it still is. So it was well-suited to address the sovereign debt crisis in 2009 from the perspective of the countries that collectively comprise almost 90 percent of the world’s economy. What we have today is not a global banking crisis, but a pandemic that, in addition to its global health impacts, has delivered a huge economic shock to all economies. Given this group’s traditional focus, it was therefore not surprising that among the first pandemic actions taken in March 2020 was the coordination among G20 central bankers to inject $5 trillion of liquidity into the global economy as a stabilization initiative. Other measures followed, chiefly designed to support the efforts of the World Health Organization (WHO) to deal with vaccination efforts, in particular the establishment of the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A). All 2020 G20 meetings, including the Summit in Riyadh, were virtual. This led to one of the more interesting, if not bizarre G20 family photos. The big difference this year is that leaders will meet in Rome and it will be the first “cross-sectional”, in-person summit in two years. By cross-sectional, I mean a diverse group that would not normally meet in regional or specialized summits such as the G7 or NATO.

LVD: China’s evolving economic leverage has influenced the composition around the table of democratic leaders vs. illiberal/authoritarian leaders. To what degree does that make consensus more difficult?

SPB: Several ministerial meetings have taken place and the leaders’ personal representatives or “sherpas” have been zooming regularly. On the ministerial side, finance ministers and central bankers met two weeks ago to set out the parameters for the leaders’ discussion. There was agreement on debt service suspension for poorer countries most directly effected by the pandemic and the economic collapse; on a new international minimum corporate tax and the ongoing role of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the transfer of $650 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from rich to poor countries. Similarly, leaders also had a virtual meeting on Afghanistan to agree on approaches for humanitarian assistance, rejection of Afghanistan as a base for terrorism, safe passage for those Afghans wishing to leave, provision of Covid vaccines under the COVAX facility and a discussion of how to prevent the erosion of the human rights of women and girls. This was all achieved through consensus and I have not seen any indication that any government, illiberal or otherwise, wished to impede those initiatives. That noted, there will be tensions around the table, given the fact that the 20 countries (and the additional eight invited) have a complex web of bilateral relations among themselves. With each leader speaking for perhaps five minutes over the course of the summit, there will be ample time for planned and unplanned bilateral meetings, choreographed “pull asides” and “bump intos” (all part of diplomatic art these days) or just serendipitous encounters (they can often be the best or most frightening). Canada usually finds itself sitting alphabetically between Brazil and China, which can lead to table conversation depending on the inclination of the protagonists and the availability of interpreters. Or not, as we have seen.

LVD: The theme for this G20 is “People, Planet, Prosperity,” with additional emphasis on the “planet” based on its timing immediately ahead of Glasgow COP26. With the effectiveness of existing multilateral institutions under a sort of narrative siege by tactical intractability, how great is the pressure to blow through that and produce results in Rome that will bode well for Glasgow?

SPB: The G20 Chair is Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, who is an experienced internationalist, particularly in the economic area [Draghi is former European Central Bank president]. On the “People” theme, the goal will be to generate more funding to fight the pandemic and to achieve a vaccination rate of 70 percent of the world’s population for at least one jab by the end of 2022. Rather than “tactical intractability”, global institutions have responded and revitalizing the WHO is on the agenda. Global institutions have their detractors, particularly in the heat of political debate, but no one has come up with a master plan to blow everything up and start anew. Rather, the institutions have evolved, ACT-A and COVAX could not have been developed without a multilateral rules-based framework. On “Prosperity”, the overarching message will be for the G20 to demonstrate solidarity in continuing to coordinate fiscal and monetary stimulus among each other and through the IFIs to fuel the recovery while being mindful of inflationary pressures. On “Planet”, I am certain that Draghi has been coordinating approaches with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson to ensure that the G20 can act as a fulcrum for Glasgow COP 26. There will be, as there have been, concerns about agreement on the 1.5 degree temperature increase target, the phasing out of coal subsidies and the question of the delivery plan for $100 billion on climate finance (where Germany and Canada have worked together to produce the plan) that countries agreed to a decade ago. None of this is surprising, but if the G20 can go to Glasgow with some consensual positions this will certainly send a strong message to that conference and to concerned citizens across the globe.

LVD: Do you think the G20 will exist a decade from now?

SPB: I am often reminded of the great line in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s masterful novella “Chronicle of a Death Foretold”: “ None of us could go on living without an exact knowledge of the mission assigned to us by fate.” Global governance is hard. Informal groupings, like the G7 and G20, are often seen as being on the verge of their demise. Too many differing views, lofty words, no discernible action. All true, but only to a degree. These groups will last as long as they are useful fora for interaction, discussion, debate and initiative. Often slow, sometimes with greater urgency. Our fate as humanity is that we need to interact with each other across cultural, linguistic, ideological and sovereign divides. Not an easy task, but these high level meetings help. Yet this is the mission assigned to us by fate.

Senator Peter Boehm, a regular contributor to Policy magazine, is a former senior diplomat. He served as ambassador to Germany, senior associate deputy minister at Foreign Affairs, deputy minister of international development, and deputy minister for the 2018 G7 summit in Charlevoix. He served as Canada’s Sherpa for six G7 summits.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor and deputy publisher of Policy Magazine. She was Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.