Canada has a Prime Minister, Campaign or No Campaign, and the Media Should Say So

Some media stop referring to the prime minister as the prime minister during election campaigns. Constitutional expert Philippe Lagassé says that relatively new practice sacrifices accuracy in the name of objectivity.

Philippe Lagassé

August 17, 2021

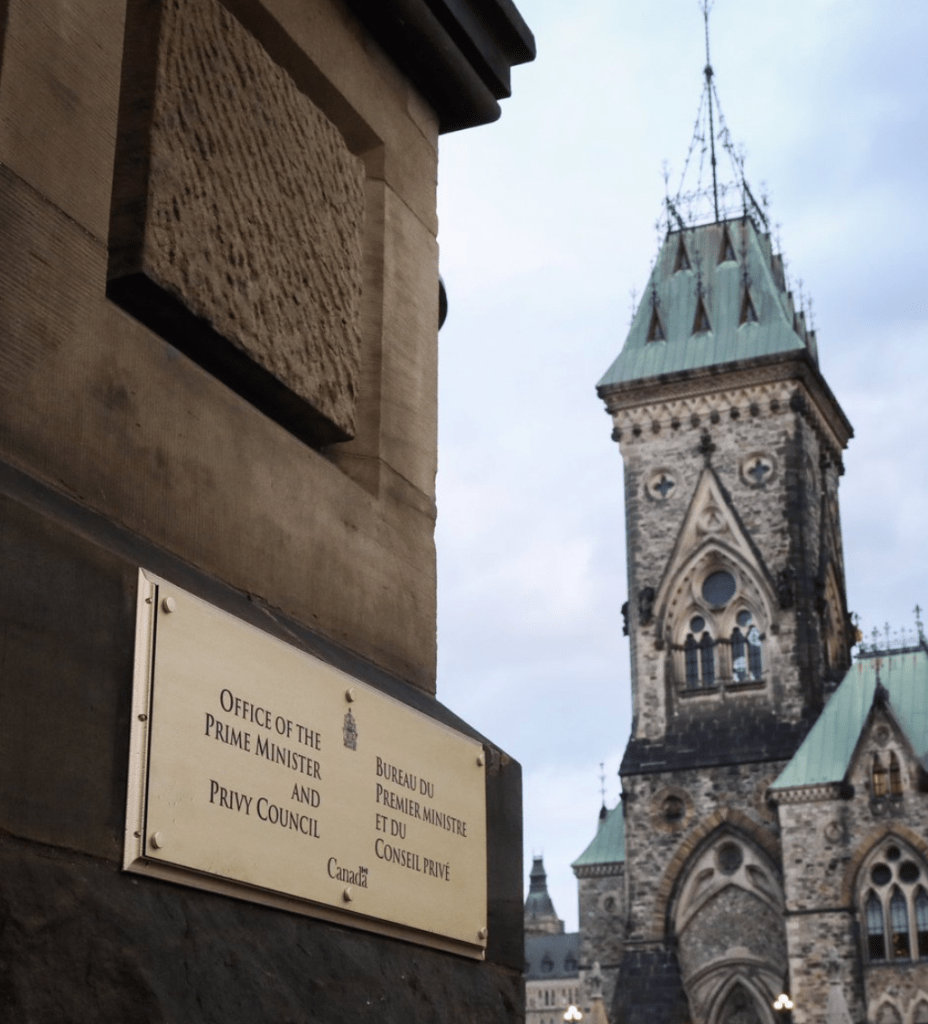

Justin Trudeau is still the prime minister and responsible for all affairs of government. This should not be obscured, despite the general election.

In recent years, certain media outlets have decided that the prime minister should only be referred to as the leader of their party when an election is underway. Hence, Prime Minister Stephen Harper was referred to as the Conservative leader during the 2015 election, and Prime Minister Trudeau is currently being identified only as “Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau”. This practice is misleading and confuses Canadians about how their government operates. Although only calling Trudeau the Liberal leader may theoretically level the electoral playing field, the editorial rationale for the decision should be rethought.

The choice to disregard the title of prime minister during an election is well-intentioned. Various studies suggest that incumbents have an advantage at the polls and identifying the prime minister as such may imbue them with an aura of greater stature or authority. To ensure that they are impartial in their coverage, media outlets may believe that it is better to only talk about party leaders, notwithstanding the fact that one of them remains prime minister while Parliament is dissolved.

A skeptical mind might have doubts about the incumbency advantage as applied to the prime minister in Canada: Is the advantage tied to name recognition or the office they hold? Would citizens who are unable to identify the prime minister be less invested in politics and therefore less likely to vote? If the government is unpopular or people simply want change, would that not create an incumbency disadvantage? These are puzzles for researchers to solve. For argument’s sake, let us assume that the media are right that naming the prime minister could unduly advantage their party. Would that not weigh heavily in favour of not identifying the head of government? Perhaps. But we should be honest about the costs.

During the 2019 election, with polls suggesting that we were headed toward a minority Parliament, the question of which party gets to govern arose. Customarily, the party that wins the most seats governs, but this is not a constitutional requirement. Because the prime minister remains in office during the election, and indeed until they resign or are dismissed by the Governor General, they have the option of trying to test the confidence of the Commons first, even if their party did not win the most seats (see Premier Brian Gallant following the 2018 New Brunswick election for a recent example). If they negotiate a deal with another party, they can hope to stay in power, however tenuously, as Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King did in 1925.

When media do not identify the prime minister, it becomes more difficult to explain why a party that wins fewer seats can stay in power. Indeed, it might give the impression that a prime minister who chooses to stay on is acting illegitimately, when doing so is constitutionally permissible. Since the ability of the prime minister to meet the Commons first — regardless of the election result — is directly tied to the office they hold, not acknowledging that they hold that office sows confusion about how our constitution works.

The day Parliament was dissolved, the Taliban took Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan. In the days that have followed, we have seen Afghans rushing to the Kabul airport trying to escape Taliban rule, many of them because they fear retaliation for having cooperated with allied military forces during the past two decades. The Canadian government has sent military aircraft to assist with evacuation efforts. As Canada responds to this unfolding crisis, there should be no doubt who is in charge: the prime minister and cabinet. Although the Canadian military and public servants are undertaking and managing these operations, they rely on the authorization of ministers. The fact that these ministers are in the midst of an electoral campaign surely makes things more complicated, but their decisions and authority are nonetheless required to power the machinery of government. Their roles in formulating Canada’s foreign policy — especially in a crisis — is something voters should be free to judge them on without the filter of misrepresentational nomenclature.

As importantly, the prime minister and cabinet remain accountable for Canada’s handling of the ongoing crisis in Afghanistan. It would be both inaccurate and highly inappropriate to suggest or report that Trudeau is making decisions here solely in his capacity as the Liberal leader. Trudeau has the responsibility and authority to address this crisis because he is the prime minister. That should be crystal clear to Canadians and media should not cloud their perceptions.

Shortly before the election was called, Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer warned that we had entered the fourth wave of Covid-19. With a large percentage of Canadians having had two vaccines doses, this fourth wave may not be as severe as the first three, but caution and vigilance remain vital. As has been the case since the pandemic began, provinces and municipalities will be at the forefront of Canada’s handling of the pandemic. Nonetheless, the federal government has unique competencies, such as those surrounding international travel restrictions, vaccine procurement, and military assistance to affected communities. If all goes well, federal ministers will not need to make any significant decisions in these areas until the election is over. But if they do, it should be obvious that they are in charge and that they have the power to act. Here again, Canadians should know this and media should not complicate this reality.

Canada has a prime minister right now. While the election may change who holds that office, there should be no doubt in Canadians’ minds — or in the minds of citizens elsewhere whose heads of state and government interact with Canada’s prime minister on a daily basis — about who is heading the government.

Philippe Lagassé is associate professor and the Barton Chair at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs at Carleton University. Lagassé’s research focus includes the role of Parliament and the Crown, and executive power in Westminster states, notably in the areas of foreign and military affairs.