Postcard from Davos: Close Encounters and Karaoke in the Global Village

WEF founder Klaus Schwab and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Davos, January 16, 2024/WEF image

WEF founder Klaus Schwab and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in Davos, January 16, 2024/WEF image

By John Stackhouse

January 30, 2024

I have a love-hate relationship with the Hotel Europe in Davos. But mostly hate.

There’s nothing obvious to hate about the skier’s inn on Davos’ main Promenade. Its undersized rooms and oversized spread of breakfast cold cuts are no different than most mid-market hotels in town. Only problem is that for one week in January, it is overrun by globalist partygoers in town for what the New York Times once referred to as the Super Bowl of global capitalism.

For the better part of a decade, I’ve been consigned to the Europe for that week by the agency that runs something of a monopoly on room allocations during the World Economic Forum (WEF). Despite my efforts to move, they seem to have an immovable Hotel California policy where my billeting at the Europe is concerned. I’m pretty sure that during the WEF annual meeting, I’ve never slept more than two hours, thanks to the 150-decibel pulsations of the Europe’s legendary Tonic Piano Bar. This year they put me in the room directly above it, and the raucous crowds that spill down its sweeping main staircase.

Hotel Europe, Davos: Where ‘The Mooch’ meets Leonard Cohen/Snowtrex

Hotel Europe, Davos: Where ‘The Mooch’ meets Leonard Cohen/Snowtrex

On Tuesday nights, the hedge fund investor Anthony Scaramucci, a.k.a “The Mooch”, who served the shortest tenure on record for a White House director of communications under Donald Trump, hosts a notorious wine-tasting party in the Piano Bar that draws hundreds of WEF-goers and stays open to 4.

On Wednesday, the overflow crowd was so thick that this year I had to get hotel security to help me to my room. The crowd and piano player sang (terribly) to every known tune from ‘80s Karaoke — a Piano Bar tradition. Finally, at 4:30 a.m., as they droned through a tortured version of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, I went to the front desk to plead mercy. The overnight manager shook his head, and handed me a pair of ear plugs.

On Thursday nights, Salesforce billionaire Marc Benioff rents out a separate bar, adjacent to the hotel, and flies in bands like the Black Eyed Peas. The revelers waiting outside the invite-only event leave such a trail that on Friday mornings the Europe doorway is strewn with broken glass.

Don’t get me wrong. The Europe isn’t all bad. In 2016, when I first stayed there, I wandered into the Piano Bar and quickly realized I was seated next to the actor Kevin Spacey, who was seated next to the Republican congressman Kevin McCarthy, who was coaching the since-disagreed star of House of Cards on how to talk like a politician.

They were happy to be diverted by an intrusive Canadian, and opened up as to how they genuinely wanted to swap roles. We then talked at some length about Donald Trump — at the time an outsider to the GOP nomination — and why they both considered him a shoo-in. To McCarthy, Trump captured the discontent among American voters with anything that smacked of the establishment. To Spacey, it was a matter of form. Trump was an actor’s actor — a guy who played a role without even thinking he was role-playing. A natural. McCarthy took it further, arguing that every president represents the defining media of their time — Reagan, television; Clinton, cable; Obama, social. Get ready for the reality TV president, he said.

That’s Davos, a place where for one week in January, you can talk to almost anyone at almost any time about almost anything. I’ve had hallway conversations with Bono, lunch chats with Queen Maxima of the Netherlands, and this year, an impromptu exchange with an American executive who had just been on the phone with Benjamin Netanyahu.

I got stuck in a gondola one year with Daniel Yergin, the world’s pre-eminent energy thinker, who gave me a masterclass on OPEC. Another year, I found myself in a hotel security line behind Blackstone CEO Steve Schwarzman, the Wall Street titan, and struck up a conversation about China. I complimented his scholarship program for Americans to study there, and he quickly pulled me away from the line to explain in some detail the real views of Trump among the Beijing leadership, who he knows well.

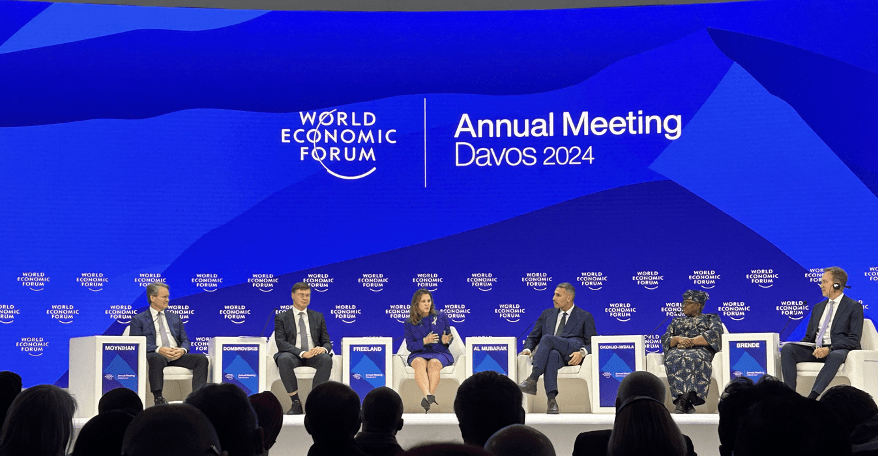

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland (centre) participates in a trade panel, January 18, 2024/John Stackhouse

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland (centre) participates in a trade panel, January 18, 2024/John Stackhouse

For 51 weeks of the year, the town of 11,000 and its dated hotels go largely unnoticed. But for one week in January, Davos’s population surges to 30,000 as global leaders, executives, journalists, activists and celebrities come for the WEF. This year, there were 4,000 soldiers and police, 500 journalists, 300 cabinet ministers and so many management consultants that locals could rent out their apartments for $30,000 for the week and flee to the Côte d’Azur.

It’s much more than a super-sized social network. Pension fund managers tell me they cover more meetings with more companies from more countries in one week than they could in months of travel. Economic development teams will tell you they get to meet with more potential investors than they could ever get to visit their countries, states or provinces.

It’s an unusual meeting ground, where in one room diplomats may be trying to sketch out a peace deal, while in the next room two CEOs may be cooking up a corporate merger. It’s perhaps the only place you can find Nobel Prize winners in economics, peace and physics in the same room. For observers like me, it’s a rare concentration of brains, influence and perspectives that helps make sense of a disrupted and fractious world. (You can read my summary of this year’s forum, A Year of Creative Destruction — or Just Destruction? at RBC Thought Leadership.)

Ironically, this year’s Forum was about trust, and you don’t get these spontaneous conversations without some sort of implicit trust. It speaks to the cloistered nature of Davos, which is both a full-on media event — teeming with journalists and simulcast to the world — and a casual venue where CEOs and central bankers, fund managers and entrepreneurs, can grab a coffee.

The most interesting conversations, I found, were with the eclectic mix of inventors, innovators, artists and activists whom it attracts. Among many connections from this year’s Forum, I’ve stayed in touch with a women’s rights activists from India, a carbon trader from Kenya and a climate scientist from Cambridge.

The Schatzalp Sanatorium, setting of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, now a hotel/Berghotel Schatzalp

The Schatzalp Sanatorium, setting of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, now a hotel/Berghotel Schatzalp

A century ago, Davos was known among Europe’s gilded set as the Magic Mountain, made famous by the Thomas Mann novel for the healing powers of its crisp air, hot springs and tuberculosis sanatorium, now a hotel, high above the town. Today, it’s a sleepy resort that because of the Forum has become synonymous with elitism and globalism, not unfairly so. But if it has a magic, it’s in its ability to draw such a diverse crowd — even those who like to express their inner Leonard Cohen at sunrise.

One of my favourite sights is the town’s main Promenade, where shopkeepers rent out their boutiques and cafes to rising economic powers such as India and Saudi Arabia, and tech powers like Meta and Amazon, to tell the world about their strengths and ambitions. Beyond the commercial centres, the hotels along the Promenade are packed with breakfast forums, lunch speeches and late-night hotel parties. Much of the crowd are pilot fish — consultants, sales reps, journalists — trailing the sharks of business and government. But as the Davos organizers like to say, an ever-more complex and complicated world needs to find places to come together.

The Forum is one of the few places where business and government, academics, community organizers and NGOs can do that. This year, despite the mood being economically tepid, politically sour, AI-obsessed and security skittish, the converations kept an even keel. Next year, anyone of those themes could reemege. I just hope there will be more signal than noise, especially at the Europe.

John Stackhouse, Senior Vice President in the Office of the CEO at Royal Bank of Canada, is also a former Editor-in-Chief of the Globe and Mail. He is a Senior Fellow of the C.D. Howe Institute as well as the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.