Reading the IMF’s Latest Worldview

Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

August 12, 2023

In late July, the International Monetary Fund saw fit to revisit its World Economic Outlook for this year and next in the face of continuing inflation pressures eliciting further central bank tightening in western economies and signs of a weak bounce-back in China after the ending of its pandemic lockdowns. Digesting recent developments around the world, the IMF has tweaked its global outlook slightly, but kept its economic and policy messages largely unchanged.

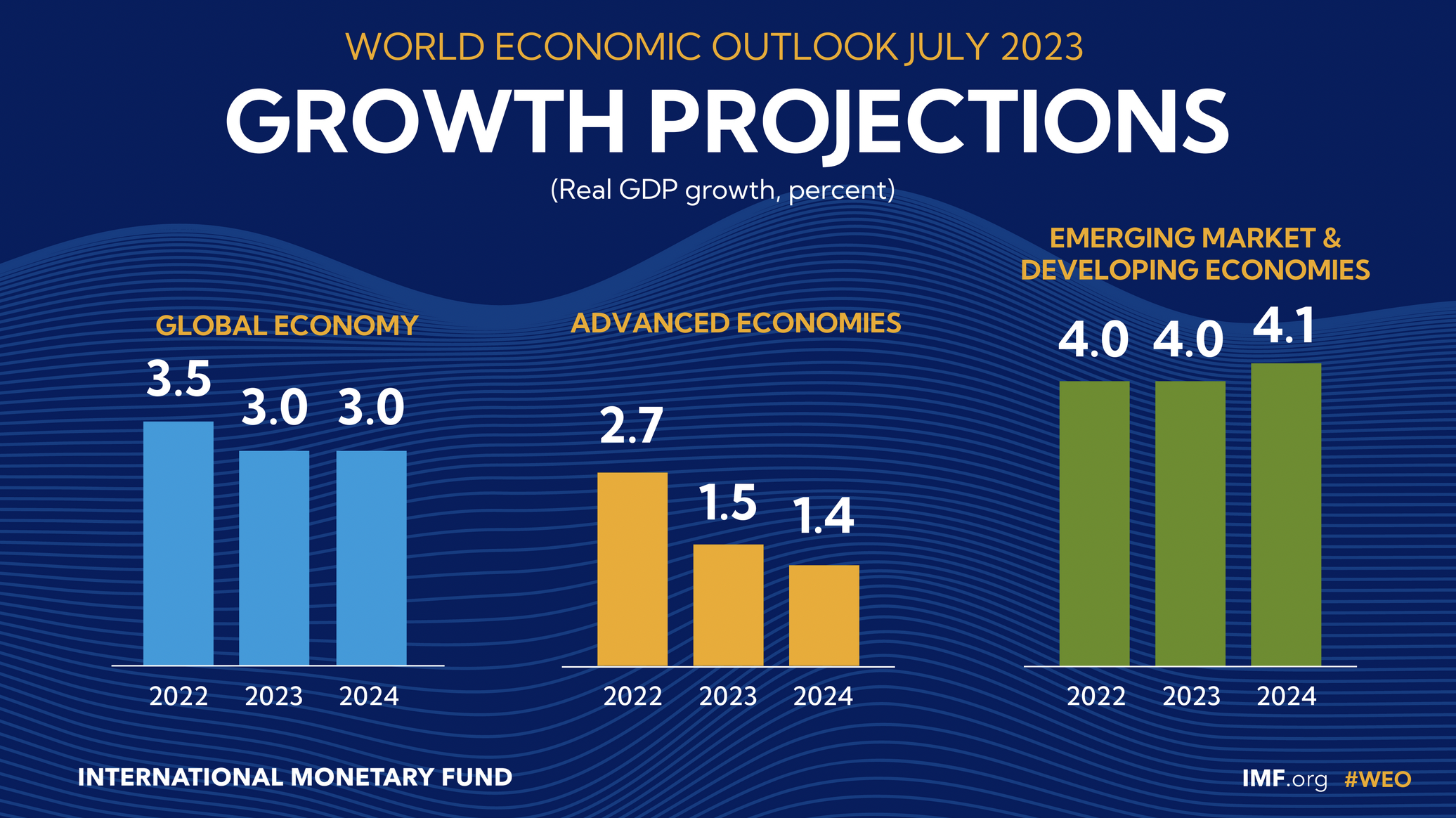

Global growth is expected to be subdued both this year and in 2024. At 3 percent, growth is well below its average over the 2000-2019 period of 3.8 percent, but a slight uptick of 0.2 percent from April’s projections. Underlying this global average, advanced countries are expected to grow around 1.5 percent while emerging markets should expand about 4 percent in both years. The emerging market surprise is China, whose recovery from the pandemic lockdowns is losing steam. There are a number of possible culprits: excessive debt and bankruptcies in the key real estate sector is one, reduced export demand due to the global slowdown as well as trade frictions is another, and President Xi’s attacks on, and interference in, the entrepreneurial private sector in China cannot be a boon for business confidence or investment.

For the advanced countries, but particularly the United States, the biggest surprise has been the rebound of consumers spending on the services they couldn’t access during the pandemic, drawing down “pandemic savings” to do so despite the rise in interest rates. Goods spending by households, on the other hand, has softened, triggering weakness in the manufacturing and industrial sectors. While the IMF expects further slowing in growth as interest rate hikes bite more deeply as mortgages and debt are renewed, it is silent on whether a US “hard landing” will be necessary to achieve the Fed’s quest to get inflation back to target, or whether a “soft landing” is possible given the robustness of labour markets. Similar unknowns puzzle policy makers, business leaders and financial markets in the EU, UK and Canada.

The IMF projects Canada’s GDP growth this year at 1.7 percent, half that of last year, and slightly lower in 2024 (1.4 percent). This largely mirrors their growth forecasts for the United States and is a tad higher than projections for other G7 countries.

The type of landing is inextricably linked to the stickiness of inflation. In most advanced countries, inflation is easing but remains high relative to inflation targets. Indeed, the central driver of lower headline inflation so far has been declines in energy and commodity prices from their early 2022 peaks. Core inflation has been much stickier as headline inflation has passed into wage- and price-setting behaviour and expectations. Based on their analysis, the IMF projects inflation to “remain above target in 2023 in 96 percent of economies with inflation targets and in 89 percent of those economies in 2024.” This suggests interest rates will stay high for longer, and the key uncertainty for growth is what it will take for central banks to re-anchor inflation expectations at their target.

The IMF projects Canada’s GDP growth this year at 1.7 percent, half that of last year, and slightly lower in 2024 (1.4 percent). This largely mirrors their growth forecasts for the United States and is a tad higher than projections for other G7 countries. While not part of the IMF update, an important difference in drivers of growth between Canada and other G7 countries is population growth. Canada’s population will likely grow by 2.5 percent this year, driven almost entirely by immigration, while U.S. population growth will be about 0.5 percent, with lower still or negative population expansion in other G7 countries. As a result, unlike those other G7 countries, Canada’s GDP per capita –a common measure of standards of living – will actually decline both this year and next.

World trade will weaken more than global growth, expanding only 2 percent this year, as slowing goods demand, lingering supply chain challenges, trade restrictions, and the war in Ukraine take their toll. Over the two decades before the pandemic, growth in world trade, which averaged 4.9 percent, led GDP growth as globalization deepened and China became the world’s largest exporter of goods. With geopolitical tensions worsening, the IMF fears that trade and investment fragmentation will intensify as further restrictions are placed on foreign investments, cross border movements of technology and people, access to critical minerals and international payments systems. One consequence will be higher costs for manufactured goods and greater volatility in commodity prices.

The policy messages from the IMF to governments and the public in the update are similar to before, but sharper.

First and foremost, “conquer inflation”, and this includes more complementary fiscal policy actions to support restrictive monetary policy. Second, rebuild fiscal buffers to restore budgetary room for manoeuvre and fiscal sustainability in the face of fiscal deficits and debt above pre-pandemic levels. Third, maintain financial sector stability in the new world of high interest rates and respond to pressures quickly as the Fed and Swiss did recently when confronted by banking stresses. Fourth, ease the funding squeeze for developing countries as it is a highly integrated global capital market and economy where weakness anywhere can spread everywhere. And fifth, work on the supply side to build resiliency and flexibility in both domestic and global supply chains.

In a blog post on the IMF World Economic Outlook July update, the IMF’s Chief Economist Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas commented: “Hopefully, with inflation starting to recede, we have entered the final stage of the inflationary cycle that started in 2021. But hope is not a policy, and the touchdown may prove quite tricky to execute.” And hence the quite clear and focused IMF policy advice to governments and central banks.

Kevin Lynch was Clerk of the Privy Council and vice chair of BMO Financial Group.

Paul Deegan was a public affairs executive at BMO and CN.