Rediscovering Competitiveness: In Search of a ‘Growth Anchor’?

We live in a time when, it seems, all disasters are global and none of them can be contained either geographically or sectorally. The COVID pandemic contributed to supply chain bottlenecks that are being further exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which is also contributing to a burgeoning international food crisis. In such an environment, the resilience of the Canadian economy matters. As former clerk of the Privy Council Kevin Lynch and former White House economic aide Paul Deegan write, economic growth and competitiveness are key components of that resilience.

Kevin Lynch and Paul Deegan

Covid-19 has dominated our lives and monopolized the attention of policy-makers around the globe since 2020. As we emerge from the pandemic, or learn to live with Covid, Canadian policy-makers need to re-focus on competitiveness.

As an economic policy priority, competitiveness is the consummate multi-tasker: it not only drives growth and living standards, it also shapes the fiscal capacity of governments, determines our trade balance, and is a core element of a country’s global brand, influencing foreign investment decisions. A case in point is the relationship among competitiveness, economic growth, and fiscal stability: a sustainable fiscal policy requires both a growth anchor and a fiscal anchor, and we have neither.

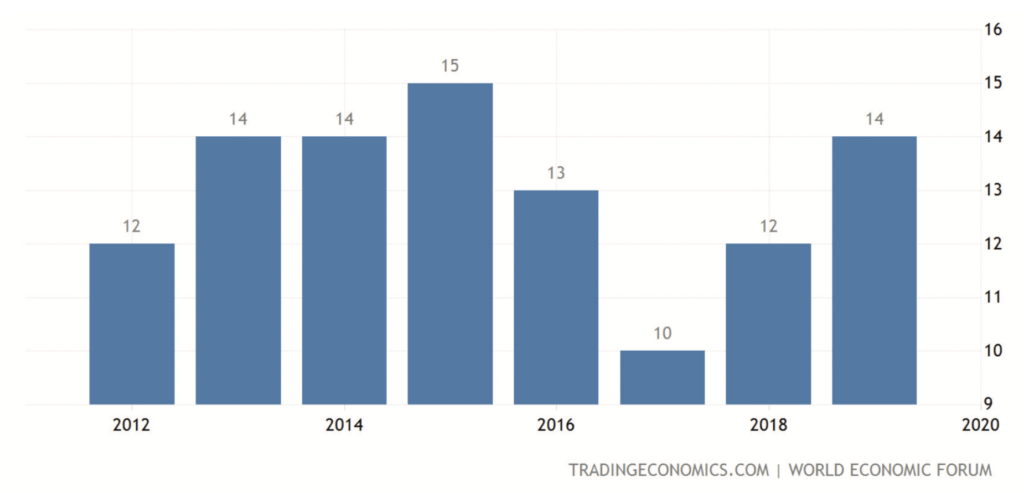

A good way to start any competitiveness journey is with some basic facts. Here, looking at the main international competitiveness rankings, Before the pandemic, Canada stood 14th on the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index –- not great, in fact not even particularly good, as we rank much lower in many of the key variables that drive future competitiveness.

As Michael Porter presciently observed almost two decades ago: “A nation’s competitiveness depends on the capacity of its industry to innovate and upgrade …and in a world of increasingly global competition, nations have become more, not less, important.” In today’s world of constant technological change, it is more and more difficult to be competitive in any sector of the economy if you are not innovative, and Canada ranks only 21st in innovation, 24th in private sector R&D spending, 35th in private sector diffusion/adoption of new digital technologies, and 26th in infrastructure (including digital). Ottawa, we have a problem.

This weakness in competitiveness is mirrored in our poor productivity performance. Productivity levels in Canada (GDP per hour worked) are now estimated at only 74 percent of those in the United States, and this gap has widened over the last decade. Productivity levels are more than impersonal statistical calculations: they matter for wages and incomes. Shockingly, this gap in productivity levels translates into a chasm today between Canadian and American living standards of roughly $22,500 per household.

Not surprisingly, competitiveness and trade are strongly linked. Canada’s trade is highly concentrated, both geographically and in the nature of the products we export. The US accounts for roughly 75 percent of our exports, but Canada’s share of US imports has been declining for over a decade, and particularly so for manufactured goods and services. With the new NAFTA, or Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) already running into protectionist headwinds from the Biden administration, combined with holdover “Buy America” policies from the Trump years, holding market share will be a challenge going forward unless we offer competitive and innovative products in a very competitive marketplace.

The product concentration of our exports is equally striking: natural resources (oil, gas, coal, hydro, lumber, etc.) and transportation equipment (cars and car parts) account for 70 percent of goods exports, and over 50 percent of total exports of both goods and services. If you add in five other energy-intensive industries – aluminum, pulp and paper, chemicals, and fertilizers – it adds up to the vast majority of our export trade. And all are now at significant policy risk: climate change and decarbonization (oil, gas, and coal); Buy America preferences (auto sector, pipelines, infrastructure), US punitive tariffs (lumber) and geopolitical trade disputes (China, Russia).

Attitudes, both corporate and governmental, matter for competitiveness. Canada is a trading nation but not a nation of traders. Most of our SMEs do not engage in cross-border trade, although their competitors are increasingly international. Even among larger firms, a surprising portion of cross-border trade is intra-firm rather than competing in explicitly contested markets. Digital shopping and the “Amazon effect” are rewriting the rules of sales, marketing, logistics, price, and place, but so far Canadian firms are lagging not leading, with the exception of Shopify. And then there are the never-ending interprovincial trade barriers and the ever-increasing business regulations that governments impose without considering their competitiveness and growth effects.

So, what does all this mean for the future growth of our standards of living? A slowdown, and a long-term one at that, unless we are willing to shift our policy focus from redistribution to competitiveness and growth. Canada’s trend, or potential, growth rate was projected, pre-pandemic, to drift downward to the 1.5-1.75 percent range, largely reflecting weak productivity growth and slowing labour force growth (aging society, early retirement incentives, plateauing of female participation rates). Post-pandemic, the decline could come earlier and be sharper.

Even more telling, and troubling, is the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) view that Canada will have the weakest growth in real GDP per capita (the standard measure of aggregate living standards) of all 38 OECD member countries over the 2020-to-2030 decade, averaging only 0.7 percent per year growth, less than half of the OECD average. Is this our future?

Looking to the future, the world of competitiveness is dynamic, disruptive, and uncertain. Global trade patterns are changing, and sources of comparative advantage are shifting. Both will affect Canadian competitiveness and growth in complex ways in the months and years to come.

First, the digitalization revolution is anything but over. The fastest growing part of economies and trade is services, and within services, it is digital services trade. Here, the rules of the game will matter greatly to trade, and there is a significant risk of “digital Berlin walls” emerging between China and the West, and perhaps between the EU and the rest, as rules for data privacy, data ownership, data rights and data security diverge among the “global rule setters” and markets become segmented. Canada has to up its digital diplomacy game, being at the table with the credibility and ideas as the new digital rules are established. Here, we were pleased to see that Budget 2022 announced the government’s intention to introduce legislative amendments to the Competition Act as a preliminary phase in modernizing the competition regime, including adapting the law to today’s digital reality.

Second, the talent opportunity has to be seized. The magic sauce of the high tech, high-growth economy is talent, and attracting the best talent from around the world is an imperative for long-term success. The talent “attractors” are: education (top-tier global universities), opportunity (start ups, scale ups, frontier firms), society (values, communities) and access (immigration rules/systems). The competition is fierce from other countries such as the US, Britain and Australia, and we are scoring an unfortunate own goal these days with the ineffectiveness of Canada’s immigration processing system. The global best and brightest have multiple choices, so why wait in limbo for years to come to Canada when others beckon?

On that front, the budget’s investment ($385.7 million over five years, and $86.5 million ongoing) to speed the timely and efficient entry of a growing number of visitors, workers, and students is a good and necessary step.

Third, the impact of decarbonization on the economy. As countries such as Canada begin to adopt decarbonization policies, the spectre of de-industrialization will hang over resource- and energy-intensive sectors, and the economies and jobs they support. Politically, economies will be under great pressure to level the decarbonization playing field for their domestic firms. Besides domestic subsidy schemes, the most likely trade tool to accomplish this is the border carbon adjustment measure. This has the potential to be the big new trade barrier if there is not an agreed upon international approach to how it can be designed and deployed. Canada should have a clear policy view and a plan, and the budget did not provide one.

Fourth, the de-globalization threat is real. The combination of left-wing and right-wing populism presents a threat to rules-based multilateralism. In the shift from rules-to-might, and the development of geopolitical spheres of influence and trading blocks, mid-sized trading countries like Canada may be the losers. Hence, we have a disproportionate interest in preserving, modernizing, and strengthening the Bretton Woods international bodies, and this requires long-term investments by senior public servants and political leaders of time, ideas, connections, and resources.

The threats include the next generation of protectionism, likely in the areas of data, intellectual property, and advanced technologies, linked to US-China tensions and the race for global technology supremacy. They also include geopolitical uncertainty and the increasing use of sanctions to punish rogue regimes, with the financial sanctions imposed on Russia as a consequence of its invasion of Ukraine the most striking example. Indeed, the geopolitical tensions between China and the US will likely play out more on the economic front than the military one, whether it is technology competition, digital competition, infrastructure competition or critical resources competition. And somewhat paradoxically, long COVID symptoms will reshape global trading patterns, as countries and companies seek greater resiliency in global supply chains. How reshoring, near-shoring and split-shoring will affect the competitiveness of Canadian exporters and importers is still to be determined, but it will not be neutral and we cannot be passive.

Budget 2022 begins the necessary task of restoring Canada’s place in the world. To be effective at projecting soft power, a country must be capable of contributing to collective defence, and we have been a laggard in putting hard dollars towards hard power — something that the heinous Russian invasion of Ukraine reminded the world. The NATO and NORAD commitments announced in the 2022 budget will begin to restore Canada’s reputation as a reliable defence partner.

And fifth, the brand promise: is Canada really back? Brands matter, whether to consumers buying a cell phone or corporate CEOs deciding where to place their next international expansion or talented students deciding which university to apply to, or countries deciding with whom to negotiate trade agreements.

Let’s focus our brand around a competitiveness rethink. Canada has not had an in-depth review of our competitiveness since Red Wilson’s Compete to Win report during the 2008 global financial crisis, and is desperately in need of one.

The world changed significantly post-crisis, with a greater pivot in global economic and geopolitical affairs than is generally realized. For China, it indicated the western economic model was not infallible and need not be replicated to prosper; for Russia, it created room for adventurism culminating in its invasion of Ukraine; for malevolent state actors, it suggested weakness and opportunity. For the West, it began a period of slower growth, increasing inequality, rising populism, and decreasing multilateral cooperation.

It is time to stake out a new competitiveness course for Canada. While a rising tide may not lift all boats, a receding one certainly lowers them. We have to more clearly define our national interests at home to pursue an effective foreign policy abroad. A strong, competitive economy is one of those national interests.

Contributing Writer Kevin Lynch was Clerk of the Privy Council and vice chair of BMO Financial Group.

Contributing Writer Paul Deegan was Deputy Executive Director of the National Economic Council at the Clinton White House, and is a former BMO and CN Rail executive.