Remembering Ed Broadbent

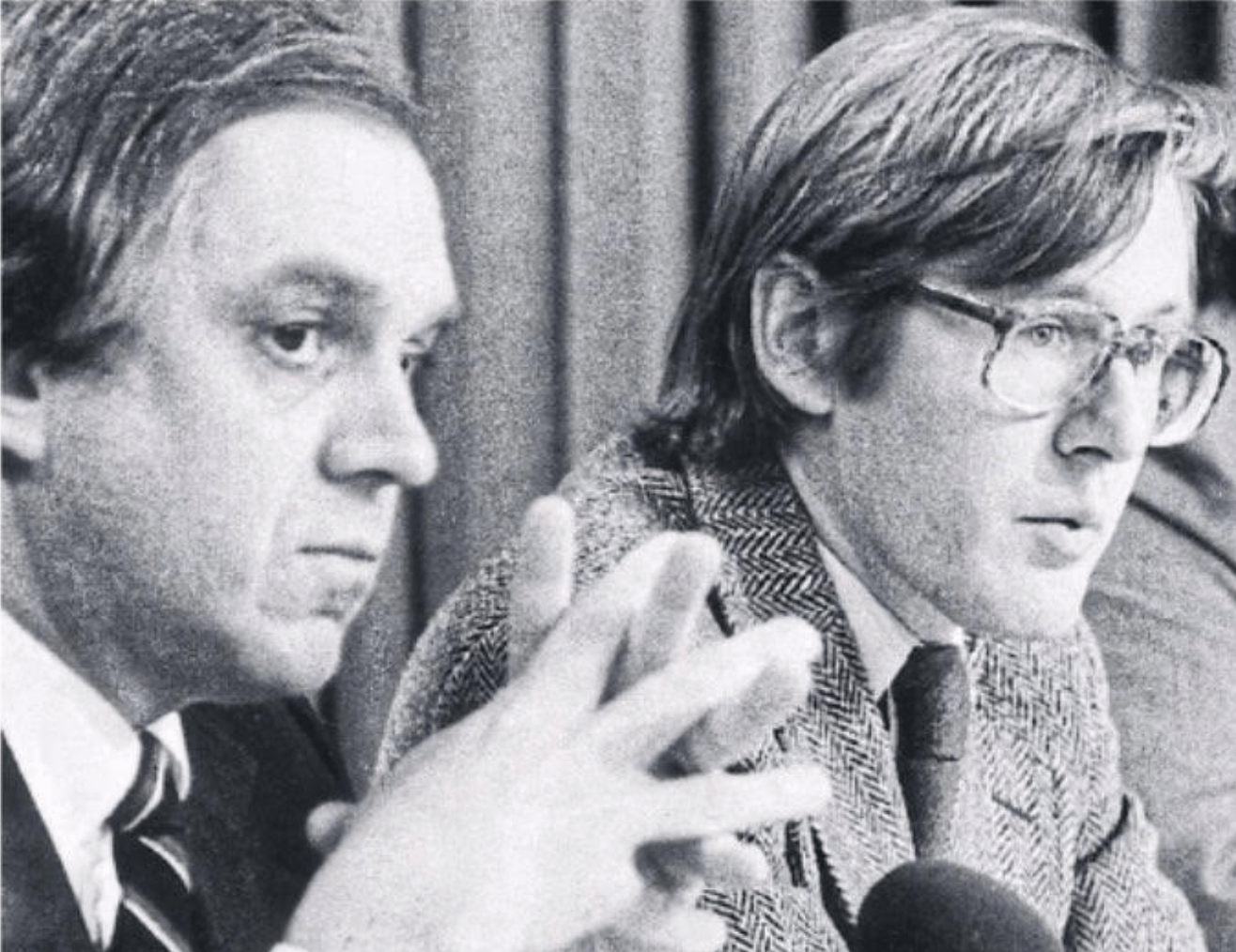

Ed Broadbent and Bob Rae, a.k.a. Batman and Robin, in 1979/Canadian Press

Ed Broadbent and Bob Rae, a.k.a. Batman and Robin, in 1979/Canadian Press

By Bob Rae

January 12, 2024

Ed Broadbent was born in Oshawa, where his father worked for General Motors and was an active member of the United Auto Workers. After a brilliant career as a student, Ed went on to write his PhD thesis on British philosopher John Stuart Mill, and taught briefly at York University as a professor of political science. He was elected to Parliament in 1968, defeating Michael Starr, who had been Minister of Labour in the Diefenbaker government, and was re-elected many times. He served from 1975 to 1988 as the Leader of the Federal New Democratic Party. On his (first) retirement, he was appointed by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney as the first president of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development (Rights & Democracy). He was a fellow of All Souls College at Oxford University from 1996-1997, and continued to work for social democratic causes in Canada and around the world. He returned to Parliament for one term under the leadership of Jack Layton, and then founded the Broadbent Institute, based in Ottawa. He died on January 11, 2024, at the age of 87.

These are the bare bones of Ed Broadbent’s public life. As a law student in the 1970s, I attended the NDP convention that elected him as leader, and soon after that was recruited to do some work on federal policy. We quickly became friends, and I then ran in a byelection in Broadview, Toronto, in the fall of 1978, where his personal encouragement and support were critical factors in my election, which was hard fought — the NDP managed to win by only a few hundred votes.

The news of Ed’s death, for me and for all those who knew him and worked for him, has brought back a flood of memories of a man widely recognized for his decency, intelligence, and deep commitment to social democracy. Following the leadership of legendary party founders Tommy Douglas and David Lewis, Ed had the challenging task of leading the party after the re-election of a majority Liberal government in 1974. Reduced to a few seats, it was not easy.

His leadership style was collegial. Even a small caucus could be cantankerous, but he listened and learned, and the election of 1979, which led to the defeat of the Liberals and the election of Joe Clark’s Conservatives, brought a new generation of NDP MPs into the House of Commons. We were a rowdy group. Ed led us with good humour and a willingness to engage. In those days, the political atmosphere on Parliament Hill and in the House was much more collegial — the job itself considerably more fun. The wry Toronto Star columnist Richard Gwyn dubbed Ed and I ‘Batman and Robin’ (Broadbent was Batman, obviously). I so enjoyed Ed’s friendship and leadership, my life as a federal MP — and my early sense of a life in politics — would have been different were it not for his role in it.

The defeat of the Clark government in 1980 and the return of the Liberals meant that Pierre Trudeau’s determination to bring the Constitution home with a Charter of Rights would lead to a difficult debate within the New Democratic Party. Although Ed had turned down the prime minister’s offer of NDP seats at the cabinet table right after the 1980 election, the Liberals still wanted NDP support for the constitutional package, for which Ed skillfully managed to win important changes — notably respect for provincial jurisdiction on natural resources, firmer guarantees on equality rights, and, crucially, the addition of s.35 ensuring the entrenchment of Indigenous and treaty rights.

The late Ian Waddell and I often reminisced about the difference those changes made, and how Ed’s steady, practical approach kept us firmly grounded, which, given the unruly nature of our group was quite an achievement.

The wry Toronto Star columnist Richard Gwyn dubbed Ed and I ‘Batman and Robin’ (Broadbent was Batman, obviously). I so enjoyed Ed’s friendship and leadership, my life as a federal MP — and my early sense of a life in politics — would have been different were it not for his role in it.

Together with his wife Lucille, Ed regularly hosted us at his home, where he would sneak outside and smoke a cigar while joshing and joking with each one of us about the foibles of politics and the eccentricities of political colleagues, friends, and opponents. Leading an opposition caucus (something I would learn for myself when I moved to provincial politics in 1982) was never easy, but he bore it with good humour and grace.

As leader of the Party, Ed also became a stalwart member of Socialist International, the association of social democratic parties around the world. He was an avid participant in the debates in the wider movement, often reminding us that the challenges faced by Labour governments internationally required greater understanding — again, something I had to come to terms with when I led Ontario’s government in the early 90s.

Our personal relationship was, of course, strained by my decision to run for the leadership of the federal Liberals in 2006, but it did not break. He referred to it as my “apostasy”. I told him I didn’t think of a political party as a church, and that the pursuit of shared values and ideals would continue. We agreed to disagree. We spoke often during the discussions about a potential accord between the NDP and the Liberals in 2008, and he was extremely supportive of my appointments on human rights in Myanmar and later to the United Nations itself.

My favourite recollection is of a lunch Arlene and I had with Ed and Lucille in Vancouver one sunny afternoon where we reflected on personal and political wins and losses. He had just retired as President of Rights & Democracy and I had “been retired” as Premier of Ontario. His acute sense of irony was on full display, as well as his broad understanding of events both local and global. I learned much from his example, and we encouraged each other to keep going.

Politics for Ed Broadbent was not a phase or a pastime; it was a vocation. He believed in liberty, equality, and solidarity, and was deeply committed to the good fight for a world where fellowship would triumph over division and inequality. His legacy lives on in the hearts and minds of his friends and supporters, and in his lasting achievements.

Bob Rae is Canada’s Ambassador to the United Nations.