Revisiting the R Word

November 18, 2022

Douglas Porter

If the North American economy is headed for recession in the coming months, the equity market is certainly expressing its concern in an unusual fashion. The S&P 500 has quietly reeled off a 12.5% rebound from the October 12 closing lows and is now within reach of revisiting its 200-day moving average. The TSX, meanwhile, has also posted a double-digit rebound in the past six weeks to hit its highest level since June, and is now down only 4% on a year-to-date basis—a veritable flesh wound compared to some historical pre-recession action. It’s not just equities that are behaving a bit peculiarly in the face of a possible downturn—corporate spreads have narrowed, the U.S. dollar has stepped back 6% in the past two months, and industrial metals prices have firmed by more than 11% in the same period.

True, most of these market moves have only reversed a small portion of the roiling over the first nine months of the year; to wit, the MSCI World Index is still down 15% in 2022. But after being walloped through the first three quarters, the more recent bounceback is at least a suggestion that the coming economic blow may be lighter than earlier expected. It also strengthens the view that most of the market action in 2022 is a reset to the brave new world for interest rates, and not necessarily a foreshadowing of tougher economic times. (The deeply inverted yield curve is, however, still very much sending a loud warning signal.)

Above and beyond the firming in the markets, there are two more fundamental developments that are at least casting some doubt on the recession call. First, oil prices continue to erratically retreat. After pushing above $90 earlier this month, they have since receded below $80, and were actually below year-ago levels at one point this week for the first time in almost two years. That dimming in what had previously been a fearsome inflation driver will both clip expectations of further inflation and provide real-time relief for global consumers.

The second fundamental factor is the North American economic data flow itself. There are clearly many signs of softness—the U.S. leading indicator has dropped more than 3% in the past six months, and consumer sentiment is very downbeat. However, for every clunker, there seems to be another much more perky report. For example, the Atlanta Fed’s GDP Nowcast is currently pointing to a hearty Q4 gain of more than 4%—which, suffice it to say, is a long way from recession. (Aside, it’s notable how the bears have suddenly gone quiet on that particular indicator, after putting the klieg lights on it earlier this year when it was struggling.) And, next week’s highlight employment report is expected to post another sturdy payroll gain of about 200,000.

The details are different in Canada, but the broad theme is similar—growth is holding up better than expected. True, monthly GDP is expected to show a flat reading for September, after a five-month stream of modest 0.1%-to-0.2% gains. But, the early read on October is surprisingly strong. First, there was the blow-out employment gain (which is expected to come back to earth in the November jobs report), home sales actually managed to nudge ahead, and this week saw the power trio of flash sales indicators from retail, wholesale and manufacturing (all up by at least 1.3%). We had no growth pencilled in for Q4, and the BoC’s latest call was just a 0.5% a.r. advance, both of which look light at this point in the quarter.

Still, we are not throwing in the towel on the recession call. In fact, any resiliency in the economy may just eventually prompt an even tighter set of policies from the Fed and BoC, and prolong the process. Along those lines, we are actively looking at pushing further out the shallow recession we currently have forecast for the first half of 2023 in both economies. One perfectly reasonable view is that because it takes 12-18 months for rate hikes to be fully reflected in the economy, the cumulative impact of tightening may not hit with full force until late next year. Notably, former BoC Governor Poloz weighed in this week, warning of the potential slow-release pain of the steep rise in rates. However, the counter argument is that the impact is unfolding faster in today’s economy, and the early hikes are already hitting home.

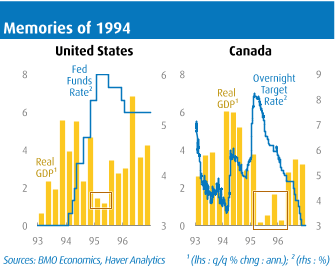

For some historical context to help settle the debate on timing, let’s look at the 1994/95 tightening episode, which is perhaps the most relevant in terms of how aggressive the Fed and BoC campaigns were. The weakest quarters for growth in that period were within a year of the onset of the rate hikes, which would still put us in early 2023 in the current cycle. For example, in that earlier episode, the Fed hiked rates by 300 bps in the year to February 1995, and GDP growth cooled from a torrid pace of above 4% in 1994 to a near-stall in the first two quarters of 1995 (at just over 1% growth)—basically within a year of the start of rate hikes. But as rates stabilized in 1995, and even backed down a bit, growth also soon stabilized and rebounded by late that year. (Aside: Note that while the Fed did trim rates 75 bps that year, it then settled at 225 bps north of the pre-tightening levels, which may prove a telling example in the current environment.)

It was a roughly similar story for Canada, which saw an even bigger back-up in interest rates in 1994/95 (in part reflecting political uncertainty at the time). The Bank’s overnight rate blasted up by more than 450 bps in the short space of a year to February 1995, which may even outdo the ultimate amount of rate hikes in the current cycle (we are looking at a total of 425 bps). The economy managed to grind through that harsh medicine without even one negative quarter, albeit GDP slowed abruptly in 1995Q2 (i.e., just over a year after the rate hikes began), and grew just 0.7% over a four-quarter period. Rates then plunged in Canada, dropping below U.S. yields for the first time in decades. However, the difference in that cycle versus this one is that core inflation was receding from a peak of 2.6% in 1995, and promptly fell back to around 1.5%, whereas it’s north of 5% now. In other words, don’t look for rate relief anywhere close to that example, unless underlying inflation somehow miraculously melts in the year ahead.

It was a roughly similar story for Canada, which saw an even bigger back-up in interest rates in 1994/95 (in part reflecting political uncertainty at the time). The Bank’s overnight rate blasted up by more than 450 bps in the short space of a year to February 1995, which may even outdo the ultimate amount of rate hikes in the current cycle (we are looking at a total of 425 bps). The economy managed to grind through that harsh medicine without even one negative quarter, albeit GDP slowed abruptly in 1995Q2 (i.e., just over a year after the rate hikes began), and grew just 0.7% over a four-quarter period. Rates then plunged in Canada, dropping below U.S. yields for the first time in decades. However, the difference in that cycle versus this one is that core inflation was receding from a peak of 2.6% in 1995, and promptly fell back to around 1.5%, whereas it’s north of 5% now. In other words, don’t look for rate relief anywhere close to that example, unless underlying inflation somehow miraculously melts in the year ahead.

Bottom Line: The North American economy is finishing 2022 firmer than expected, supported by somewhat milder energy costs and likely also by savings stashes. This could point to a slightly later onset of outright GDP declines than earlier anticipated, although we are not pushing out the call just yet for two reasons. First, history tells us that weakness can arrive quickly when the rate hikes truly begin to bind, as in early 1995. And, second, the economic and market resiliency could just prompt an even harder push on the brakes from the Fed and the BoC.

With Black Friday upon us, analysts are engaged in the annual ritual of attempting to gauge the overall health of the economy from this weekend’s sales tallies. How quaint. There are at least a couple reasons to downplay these particular results. First, we will again stress the point that consumers are still rotating from goods to services, especially in Canada. The shock would be if spending on goods wasn’t soft in inflation-adjusted terms after a couple of blow-out years. Second, the nature of Black Friday has clearly morphed in recent years. I’ve rarely been accused of being an active shopper (miser maybe), so this is mostly hearsay, but many retailers have jumped the gun with pre-sales in the week, or even the month, ahead of the event—thereby diluting the punch. So, even a drop in sales volumes year-on-year won’t thwart the above theme of a resilient consumer.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.