Ride of the Vigilantes

Douglas Porter

October 6, 2023

“America is now less likely to avoid an economic recession” (Mohamed El-Erian)

“IMF predicts greater chance of a global ‘soft landing’” (FT reporters)

These wildly conflicting headlines are drawn from the same paper (Financial Times), from the same day (Oct. 6/23). Adding to the mix, the Wall Street Journal asks: “Is the Economy Cooling or Revving Up?” Yes, the economic outlook remains clear as mud. The ready explanation for the starkly differing views is that the IMF can sometimes trail a bit behind market events, and the soft-landing tale was so last month. Crashing the party, a ferocious bear market in bonds has since upended that upbeat narrative, and quickly revived risks of a hard landing.

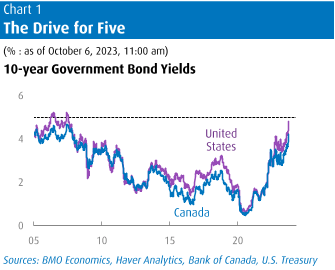

What goes up, has to come down: Tell that to the remorseless bond market. Since the end of August, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield has flared by 70 bps to 4.8%, the highest since 2007. Tens rose roughly 20 bps this week alone, while 30-year yields were even frothier, taking aim at 5% before subsiding ever so slightly by week’s end. The brutal sell-off is not really due to a deteriorating inflation backdrop, as almost the entire yield surge has been in real rates. To wit, the real 10-year yield has jumped by almost 100 bps just since mid-July to above 2.4%. Prior to the pandemic, it was hovering around zero, and we’re now back at levels not seen since before the financial crisis.

What has caused this sustained run-up in real yields, and the seeming return of the bond vigilantes? This week’s Focus Feature digs into many of the causes, and some of the reasons why yields could truly remain loftier for an extended period. We would specifically point to the dawning realization by financial markets of just how challenging the fiscal situation truly is, particularly in, but not confined to, the U.S. And, of course, the rising yields inflame the fiscal woes by driving up interest costs. In the past 12 months, the U.S. has spent $634 billion on interest, basically double from just five years ago, and the tally is rising by the month.

The unseemly tussle over the debt ceiling earlier this year, and the damp squib of spending “cuts” that resulted, may have finally awaked many to the fiscal reality. As a reminder, the budget deficit has almost doubled in the past year to $1.95 trillion (7% of GDP), at a time of full employment, and debt/GDP has vaulted above 100%. This week’s summary removal of House Speaker McCarthy simply highlighted the dysfunction in Washington, and the long odds against a serious fix in the deficit. Meantime, even as bloated deficits overload the bond supply pipeline, the Fed keeps pounding the market with QT, and the once-biggest foreign holder of Treasuries—China—is now an active seller.

Suffice it to say that the relentless rise in real yields is rattling other markets; the S&P 500 fell four weeks in a row, in sync with the bond sell-off, before bouncing about this week. The overall drop in the S&P from its summer high approached 8%, moderate by past Fall Classics, but a significant shift nonetheless from the full-on rally earlier this year. And, the Dow is now flat a year-to-date basis, while the TSX is down, with their lighter tech weights and heavier dividend components dragging on relative performance. The global yield surge, and the economic risks it entails, has even skewered previously high-flying oil prices. WTI suffered a 9% pullback this week to around $83, after taking a peek at the mid-90s just last week. In turn, gasoline prices are now back below year-ago levels, reinforcing the point that the bond sell-off is not being driven by inflation concerns per se.

After a brief mid-week respite, the fixed-income selling was fired up again by a strong September U.S. payroll report. Beyond the crackling headline gain of 336,000—double expectations—net upward revisions added 119,000 which, together, lifted payrolls 2.1% above year-ago levels. It wasn’t a full flush of strength: the companion household survey reported a modest 89,000 job gain, keeping the unemployment rate steady at 3.8%. Moreover, wages were a tad cooler than expected, up a modest 0.2% m/m, and clipping the annual rate a tick to 4.2%. Aside from a brief dive in 2021, that’s the calmest since pre-pandemic days and a marked moderation from last year’s apex of 5.9%.

Details aside, markets couldn’t look past the robust headline strength in jobs, and it reinforced the message that the U.S. economy still carried a head of steam through Q3. We have boosted our call on GDP for the quarter to a hearty 4.5% clip, with trade adding a surprising boost. The expected strong GDP reading will rely on nearly as strong productivity gains, as total hours worked rose at a moderate 1.5% annualized pace in Q3 (and up a modest 0.2% m/m in September alone).

Canada also saw jobs double expectations last month with a 63,800 advance, which was only enough to keep the unemployment rate steady at 5.5% amid soaring population trends. The near-universal view was that the headline flattered the strength of the economy, as all the gains were in volatile education (“Wait, what? They hire teachers in September?”), and most were in part-time jobs. Still, the job market is not cracking, and the Bank will be unimpressed with wages perking up to a 5% y/y clip. One curiousity is that Canada reported a nearly identical rise in hours worked last quarter as the U.S. (1.4% annualized), and yet we expect GDP to struggle to grow by 0.3% a.r., more than 4 percentage points slower than the U.S. forecast. The difference? Productivity, or absence thereof in Canada.

Where does this brutal bond market and solid employment gains leave the central banks? Notably, even amid the spike in long-term yields, two-years were little changed on the week, with a slight rise in the U.S. and a dip in Canada. The reality is that the fierce back-up in longer rates is doing a lot of the tightening work for policymakers, reducing the need for further hikes. This week, that was mostly offset by solid data. Thus, in terms of odds of additional hikes, what the job markets giveth, the bond carnage taketh away. We are still clinging to the view that the Fed and Bank of Canada have done enough and that, with patience, the forceful tightening of the past 18 months will subdue underlying inflation.

October is such a misunderstood month. Sure, it can be temperamental and has had its issues for stocks over the years—see 1987, okay and 1929, well, and 2008, and 1978, all right and many others—but it really isn’t such a bad month. In fact, since that slight mishap in 2008, the S&P 500 has risen on average by 2.4% in the 14 Octobers since. And, while it saw the single worst month in the post-war era (1987, down 21.7%), it also had the single best such month (1974, up 16.4%). Since 1990, we count eight separate bear markets in the S&P 500, or very near-bears (there were no less than four peak-to-trough declines of between 19%-to-20%). Of those eight tough markets, five of them hit bottom in the first half of October—in 1990, 1998, 2002, 2011, and 2022. So, contrary to its sullied reputation, October has in fact often been the month of salvation for stocks. Too bad we can’t say the same thing here in Mudville for the Blue Jays.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.