Risks On

Douglas Porter

October 13, 2023

The IMF traditionally releases its semi-annual World Economic Outlook (WEO) in April and October, with the latter often landing in the midst of intense market turmoil—thus sometimes rendering it as nearly obsolete on arrival. Sadly, this year’s effort largely followed that pattern. The main theme of the latest WEO was the “remarkable resilience” of the global economy in 2023; that would have been a reasonable highlight… two months ago. But, the relentless rise in bond yields in recent weeks is both threatening government finances everywhere, and is amping up the risks of a hard landing. Those yields were only clipped this week by some flight-to-safety in the face of the arguably even bigger risk of the escalating conflict in the Middle East. While the pullback in yields relieved some pressure on other markets—stocks nudged up on net this week—it was accompanied by a 4% rebound in oil prices.

Despite the IMF’s less-than-optimal timing, we have no major quibble with the broad brushes of its projections. The Fund looks for global growth to moderate further from 3.0% this year to 2.9% in 2024 (we’re at 2.9% and 2.7%, respectively). To be sure, that’s a below-average performance but still safely out of the recession zone, which we would peg at anything below 2% growth for the world economy. Their U.S. call is for 2.1% GDP growth this year and 1.5% next; the latter is above our 1.2%, and much higher than the latest consensus for 2024 of just 0.9%. But note that this year’s U.S. growth rate of above 2% will land above even the most optimistic forecast at the start of this year, and—incredibly—higher than last year’s growth rate (of 1.9%). Suffice it to say that no one saw that coming, which speaks to the IMF’s “remarkable resilience”, and also helps explain why higher-for-longer is now all the rage.

This is not to suggest that the IMF is donning rose-coloured glasses. Above and beyond the two emerging risks cited above, the Fund helpfully pointed to five key risks that could readily upend their sedate projections:

- China’s real estate crisis (they expect GDP growth to dip to 4.2% in 2024)

- A renewed rise or spike in commodity prices, presumably energy

- Sticky and stubborn inflation

- An abrupt and deep correction in financial markets

- Lofty debt levels, and the lack of fiscal space

Of course, that list is far from exhaustive, and each has quite different trajectories and probabilities. We would assert that the clearest risk on the list, that has the highest combination of likelihood and potential impact, would be in the number 3 spot—stubborn inflation. That conclusion will likely surprise precisely no one. In fact, that’s arguably not a risk, but a current reality. There was a taste of that in this week’s U.S. CPI report, which saw the headline coming in a tick above consensus and holding the annual rate at 3.7%. While core met expectations at +0.3%, that’s hardly a reassuring result. In the 14 years leading up to the mid-pandemic burst in prices, there was precisely one month that reported a higher core reading than September’s result—in January 2018, core prices rose 0.338%, compared with the 0.323% rise last month (and please forgive the three decimal place analysis; it’s meant to prove a point).

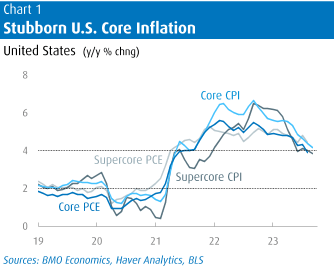

Without getting drawn too far into the weeds, the main takeaway from the CPI was that both headline and core seem to be settling into a 4% zone, or double the target (Chart 1). And this persistent underlying inflation issue has moved far beyond the supply chain pressures of days of yore (2021/22). In fact, core goods prices were unchanged from a year ago, matching the pre-COVID norm of no goods inflation. Instead, it’s all about services now, with these prices rising 5.7% y/y, and picking back up on the three-month annualized trend to 5.4%.

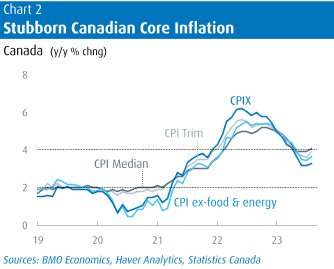

It’s a broadly similar story for Canadian inflation (Chart 2). We look for next Tuesday’s CPI release to post another headline increase just north of 4%, and most core measures to be hovering near that mark as well. (The main reason that Canada’s headline inflation is above core trends, whereas it’s the opposite in the U.S., is the weak loonie is pressuring both food and energy prices.) This report is the last major data release before the Bank of Canada’s next rate decision (Oct. 25), and will thus hold some serious sway. Market pricing points to a meaningful chance that the Bank could hike at that meeting, albeit less than 50-50, and rising in the out meetings.

Those odds received an upward jolt from a comment by Governor Macklem on Friday that higher bond yields were “not a substitute” for inflation-dampening rate hikes. That’s pretty much the opposite of what a variety of Fed speakers suggested earlier in the week which, in turn, also helped cut into lofty bond yields and dampened odds of further U.S. rate hikes. We would lean much more to the views of those Fed speakers. It’s quite apparent that the 100 bp rocket ride in five-year bond yields since the spring is now weighing heavily on the housing market, softening up large interest-sensitive swathes of the TSX, and amply reinforcing the BoC’s rate hikes. Bringing it back to the IMF, we would thus concur with one of their key conclusions from the WEO: “little further tightening is warranted”.

In a light week for data, Canadian home sales for September were the main course. A further modest dip in seasonally adjusted sales activity was no surprise, leaving them a snick above year-ago levels, nor was a modest 0.3% dip in monthly prices. But the real eye opener from the national data was the shifting balance between sales and new listings. The big story early this year was an absolute paucity of listings, as sellers refused to give in and the market came to a standstill. Now, sales are normal-ish, but listings are relatively robust, tipping the sales-to-listings ratio to the bottom of the long-term range.

This weak market balance points to another down-leg in prices in coming months. After falling by just over 15% from the February 2022 peak to the March 2023 trough, national home prices then bounced nearly 7% in the spring and early summer. As the market more fully digests the back-up in borrowing costs, we suspect that this year’s rebound will likely get reversed in coming months.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.