Self-Defence in a Dangerous Neighbourhood: Insights from Japan

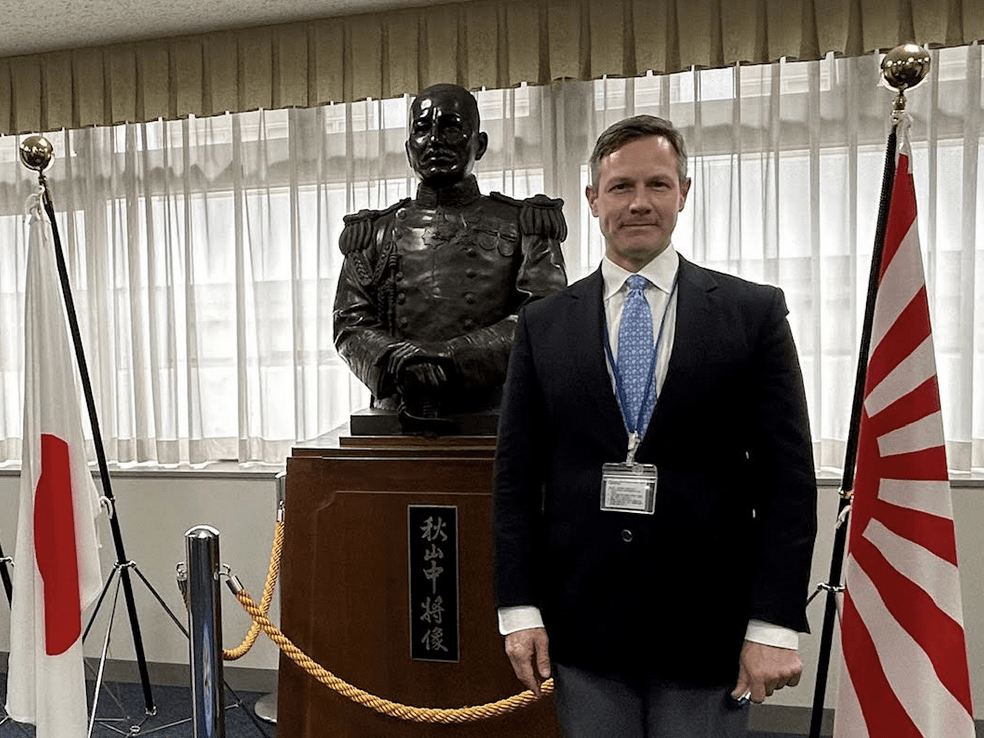

The author at Japan’s Maritime Command and Staff College, with bust of Vice Admiral Akiyama, hero of the Russo-Japanese War of 1905/Courtesy Philippe Lagassé

The author at Japan’s Maritime Command and Staff College, with bust of Vice Admiral Akiyama, hero of the Russo-Japanese War of 1905/Courtesy Philippe Lagassé

May 6, 2024

This past winter, I taught a course on contemporary warfare for Carleton’s BA in Public Administration and Public Management. The course covered the evolution of war and the challenges militaries face in modern operations. We ended the term by looking at two case studies: the war in Ukraine and a possible attack on Taiwan by China.

My mind was therefore already on military matters when I travelled to Japan shortly after the course to conduct research interviews on Japanese civil-military relations, focusing on how the Ministry of Defense and Japanese Self-Defense Forces (SDF) interact. I knew heading over that possible Chinese aggression in the region would be part of my discussions with Japanese defence officials and senior military officers. I didn’t realize how much the war in Ukraine would figure into those discussions.

As part of its 2023 defence policy, the Japanese government announced a significant increase in military spending. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s government pledged to invest approximately 43 trillion yen ($383 billion Canadian) in the military over the next five years. The government has also promised to spend 2% of GDP on defence by the end of the decade. Although these spending increases reflect a gradual shift in Japanese national security thinking over the past several decades, and there is no guarantee that these targets will be met, what is striking about these announcements is the public support that has accompanied them. Not long ago, significant defence spending increases would have been met with vocal opposition from Japan’s political left and notable segments of the population.

That opposition dates back to Japan’s post-Second World War renunciation of war, which became an element of the country’s postwar identity. Indeed, Article 9 of the Japanese constitution strictly limits the kinds of operations and weaponry the Self-Defence Forces can consider. This article states that “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes.” Missions and capabilities that are deemed offensive in nature are eschewed as a result. Similarly, it has taken a good deal of conceptual stretching to allow the defence of the Korean Peninsula and Taiwan to count as existential threats that can be answered under Article 9. Although the United States would be open to a larger Japanese military role in the Indo-Pacific, the constitutional constraints imposed on the country after the Second World War remain paramount.

Most of those I interviewed agreed that the war in Ukraine explains Japan’s new attitude toward military spending. Despite being a continent away, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reinforced the risks that Japan faces in its own region.

Indeed, perhaps the most surprising thing I learned during my trip is that Japan has a nagging fear of abandonment. This makes the war in Ukraine quite pertinent to Japanese strategic thinking. Like Ukraine, Japan has no nuclear weapons to deter an attack on its soil, and China’s military power is far greater than Russia’s. Of course, the SDF are technologically impressive and far larger than Ukraine’s armed forces.

Most of those I interviewed agreed that the war in Ukraine explains Japan’s new attitude toward military spending. Despite being a continent away, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reinforced the risks that Japan faces in its own region.

But Japan would be no match against China in the event of war. Although a Chinese attack against Japan may seem far-fetched, Ukraine has demonstrated that it cannot be discounted. To ensure that it never comes to that, Japan has been building alliances and promoting a free and open Indo-Pacific based on the ‘rule of law’, a concept that is far more palpable to China and developing countries than the ‘rules based international order’, which begs the questions of whose rules and whose order we mean. Since the end of the Second World War, Japan’s security has been guaranteed by its most important partner: the United States. As Ukraine highlights, however, American support is not always unwavering. Isolationism has crept back into mainstream political debates in Washington.

While American isolationism has been relatively restrained, Japanese leaders are worried about what the future might bring. Defence planners in particular are examining how to make Japan more self-sufficient in critical areas of military manufacturing. Here again, the war in Ukraine has highlighted the dangers of relying on external support for vital defence supplies and capabilities.

A related problem concerns Japan’s defence industrial base. Japan has been buying more military equipment from the United States, and many traditional Japanese defence suppliers, such as Toshiba and Mitsubishi, are concerned about the profitability of continuing to manufacture for the SDF. In response, the Japanese government has started exporting military capabilities. This is a relatively new endeavour for Japan, and one that comes with a steep learning curve. Japan must not only become more comfortable transferring military technology to allies, but it must also become accustomed to the very idea of selling weaponry abroad.

Even if the constitution were amended to allow Japan to have a ‘normal’ military, the SDF would still be hampered by decades of caution and risk aversion. SDF commanders have not been granted, or directed to develop, the independent initiative that is essential for contemporary warfare. A strong hierarchical culture and concerns about Article 9 have prevented this delegation of authority and action from taking root. The three branches of the SDF, furthermore, remain stove-piped. The ground, maritime, and air forces are not fully connected. They would struggle to undertake fully joint operations. The maritime forces, for example, are better able to interoperate with the U.S. Navy than mount amphibious operations with the ground and air SDF.

Thankfully, the SDF are aware of the challenges they face. Japan’s approach to defence has evolved rapidly over the past decade. Military expertise has been given its due after decades of freezing the SDF out of defence planning decisions. The country’s political leaders are coming to terms with the threats they face and with the need to shore up their defence posture. With Ukraine still fresh in their minds, the Japanese public are onside. And the United States has not shown an inclination to pull back from the Pacific. Japan, therefore, has time to improve its military and be better prepared for a possible regional crisis.

These research projects rely for their success on the collaboration of local experts. I would like to highlight the openness Japanese officials and officers showed toward our work. The Embassy of Japan in Ottawa liaised with the Ministry of Defense to organize interviews with defense officials and senior officers. The officials and officers themselves were candid and unreserved. I also had the opportunity to meet with officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and National Security Secretariat who were equally forthcoming and frank.

Finally, I could not have understood Japan’s military and defence realities without the help of fellow academics who made time to meet with me while I was in Tokyo. There is no substitute for face-to-face meetings when trying to learn about a country quickly, appreciating the subtleties and nuances that even the best books and articles cannot capture. Special thanks are therefore owed to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for funding international interview-based research, and to my Carleton University colleague Stephen Saideman, who is heading our project on defence ministries and armed forces.

Policy contributor Philippe Lagassé is associate professor and Barton Chair at the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs, Carleton University.