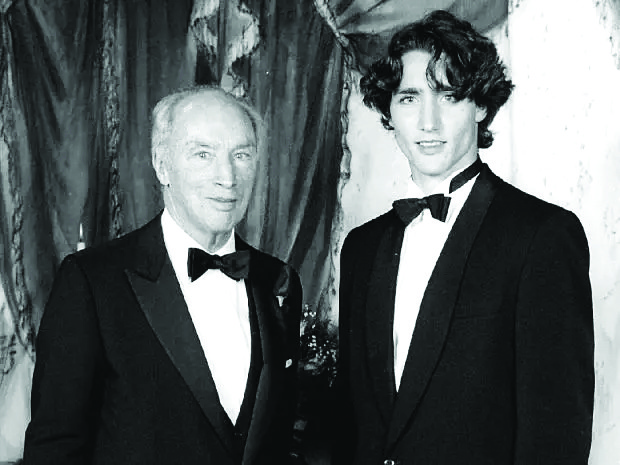

Ten Years of the Second Trudeau Era, Depending How You Count

A decade after he was Policy’s first cover subject as newly selected Liberal leader, Justin Trudeau’s future is now the most speculated-about subject in Ottawa, spun daily like a top by an antsy gaggle of touts, punters and proxies, so many of whom have undeclared stakes in the match-up for the next big fight. Longtime Liberal strategist, gimlet-eyed veteran political observer and Policy novelist-in-residence John Delacourt gives us the A.J. Liebling ringside rundown of a Trudeau decade that may have been more than just one.

John Delacourt

Decades, like centuries in political history, rarely align to the Gregorian calendar. Perhaps the

most representative example of this phenomenon is the notion that the 20th century really began in 1917 and ended in 1989, with the fall of the Berlin Wall. Those 72 years were so full of Harold MacMillan’s “events, dear boy” that there was more than enough change to contend with, and more than enough conflict and tragedy to learn from for the next century – for those in Moscow, Washington, and yes, even in Ottawa.

The second Trudeau era for the Liberals began 10 years ago, with Justin Trudeau’s virtual acclamation as leader of the party. His victory and what it meant for Canadian politics was the centerpiece topic for the first issue of this magazine. Yet has it only been 10 years since then, really? I’d argue that a new, different age of realpolitik for Trudeau as Prime Minister began in January of 2019, with a Cabinet shuffle that sent Jody Wilson-Raybould from the Justice portfolio to Veterans Affairs. A short decade of innocence and idealism concluded after six years, and a new era, defined by issues and crisis management, had begun.

It is instructive, given this framing, to go back to a year-end interview Trudeau, as leader of the Liberal party, gave to Evan Solomon on CBC in 2013. There was a list of topics the new leader was called upon to address, including a reduction in Canada Post services, a scandal regarding an audit of Senator Mike Duffy’s expenses that precipitated some less than ethical conversations involving a Deloitte consultant (okay, not McKinsey at least) and Stephen Harper’s PMO. Trudeau offered a summary condemnation of Harper’s governing style, stating it was a government that “functions in secrecy, governs by fiat and press release, announcing what they’re going to do and people can like it or lump it … that’s not the kind of government Canadians want.” He stated, less than two years before his first campaign as leader, that Canadians had “grown tired of” Harper’s style of governing. Of interest is how many times Trudeau mentioned cynicism (I counted three) to describe the defining feature — not bug — of the Harper years.

Harper’s time as prime minister, when that interview occurred, was roughly the same as Trudeau’s now. Yet the Harper decade seems as one era, a kind of Diefenbaker period of relative calm, when we were still debating whether climate change was a thing and pundits were confidently predicting the new axis point for the Canadian economy would not be Toronto but Calgary. The counter-narrative Trudeau seemed to be developing, even in those early days of his leadership, was of an approach that would re-instill idealism, bring new energy and optimism to the Canadian project, that work in progress where the middle class hadn’t “had a raise in 30 years.”

It is easy to forget, watching Trudeau in that interview, that he had been an MP on the Opposition benches for half a decade, coming in at a tumultuous time when Stéphane Dion’s leadership transitioned into Michael Ignatieff’s. To someone arriving in Ottawa with Trudeau’s cultural and legacy political capital, it must have seemed like a garrison town after the smoke of retreat, with the Liberal bench and Leader’s Office staffed with loyal foot soldiers past their best-before date (full disclosure for you, reader: I was one of them for a time) — save for a small group of allies with ties to Queen’s Park and a shrewd, survivor-class group of ninja advisers, with superior skills in opposition research and campaign operations. If you were someone with aspirations to lead and rebuild the party, you had to look outward beyond this skeleton crew to a new generation, and a new way of crafting a narrative full of hope and optimism — the oxygen of any political campaign.

A farther look back, for a moment, for some additional perspective on that six-year decade. In Christina-McCall Newman’s Grits: An Intimate Portrait of the Liberal Party, published way back in 1982, she describes when Pierre Trudeau looked to two figures, Marc Lalonde and Michael Pitfield, for counsel and ally-ship as he formulated his vision. Here’s how she described this trio:

“Their experience had persuaded them that the old bureaucratic-political axis with its generalist approach to government problems … was inadequate to cope with the complexities of the sixties. They were enamoured of cybernetics and of other technocratic ideas that they saw as a means to make government both more efficient and democratic and that fitted in perfectly with Trudeau’s views on ‘functionalism.’”

In 2013, there was another technocratic narrative emerging for another Trudeau. This one was created in the petri dish of tech-bro culture that gave us Facebook, Twitter and Amazon, and it held similar promises for our shiny new digital future. And like a bad screenplay that Amazon would probably green-light now, there was another Pitfield, Michael’s son Tom, who became the eminence grise of all things digital in the Liberals’ campaign planning.

Pitfield had learned from the success of the Obama campaign to craft a strategy of voter identification and micro-targeting, largely based on all the information Canadians had provided for free to our digital overlords. This was in that honeymoon period before Trump, and before Russian trolls had mastered mining our data and flooding the platforms with disinformation. Today the digital landscape has all the appeal – and seems as scarred – as, say Uranium City, Saskatchewan, yet it still has rich enough seams of data to yield respectable minority results that might keep Liberals in the winning column, though the Poilievre team looks like they’ve finally upped the Conservative game in data science, and in their courting of the convoyageurs and sundry PPC voters, they’ve got stronger stomachs for its darker tactics.

Yet for Canadians who live outside of Ottawa, and who at some point over the next two years have to vote, their question for a future prime minister is the same: what is the hope narrative now? The ballot question that might grant the Liberals an era beyond an actual decade cannot simply be: is — or is not — Canada broken?

Over the last month, Trudeau gave another journalist a long interview, and it was a conversation that both implicitly and explicitly addressed what I contend is this second Trudeau decade in power: its plot points marked by the Wilson-Raybould drama, the Iranian air tragedy, COVID, COVID-the-sequel, the convoy occupation of Ottawa and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. So much for history by headline; that is one plot line for a history, but there is another that simmered as a subtext, defined by transformative moments for Canadians who may have only begrudgingly granted the Liberals the keys to that crumbling ghost mansion at 24 Sussex. This counternarrative is defined by the gravesites uncovered on the grounds of shuttered residential schools, by revelations about the RCMP, and the cultural rot in our armed forces, and by similar sordid abuses of power given to young men who’ve been blessed with the talent to excel in hockey, which is of course not just our game but a kind of religion in our small towns still. You can say these Canadians are clinging onto old settler narratives that sentimentalized or outrightly lied about our encounter with First Nations, that they blindly trust those in uniform, and that they have turned a blind eye to the toxic side of hockey culture. All of that may be true, and yet for many, these are the core components of Canadian identity, and, compounded by the tribulations of the pandemic on our economy, these Canadians don’t have much to feel good about, to take pride in, to feel hopeful about.

In the interview, Trudeau leapt on this accusation, defensively. He responded as only someone who cares about the obligation to living in truth would. He said all the right things about a strong country having the courage to face up to its failures, its betrayals of trust, its crimes. He seemed to suggest that hope would reside in our ability to learn from an unvarnished take on our history, and that we would ultimately be stronger for our faith in what you might call the better angels of our nature.

You could say that within that response is something like the foundations for a new vision of Canada: something a little more grown-up to craft a narrative for a 21st century country. But you could also say it is idealistic, denying how ultimately irrational or “emotional” politics really is. We want seductive fictions, not uneasy realities as we brace ourselves for a world where we might not actually be ready to be economically competitive, progressive, “the best country in the world.”

The challenge now, for Trudeau and the Liberals around him, is to make a compelling case for hope and idealism once again and not play to the wings – where the old ghosts of realpolitik loom in the shadows more and more each day.

Contributing Writer John Delacourt, former Director of Research for the Liberal Party of Canada, is Senior Vice President of Counsel Public Affairs, based in Ottawa, He is also the author of several novels.