The Audacity of Normal: Barack Obama’s Promised Land

The first volume of the 44th president of the United States’ memoirs departs from the genre by chronicling a writer’s journey through the labyrinth of presidential power.

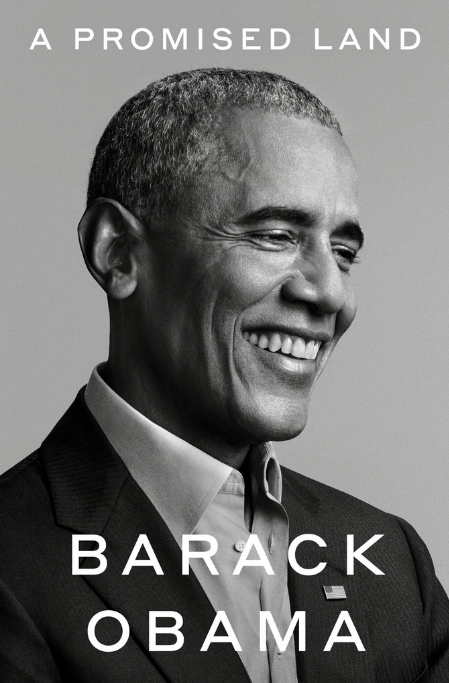

Penguin Random House/November 2020

By Barack Obama

Reviewed by Lisa Van Dusen

November 23, 2020

“Trust me, whatever else they know about you, people have noticed that you don’t look like the first 43 presidents.”

Advisor Robert Gibbs to Barack Obama.

“You may be a little too normal, too well-adjusted, to run for president.”

Advisor David Axelrod to Barack Obama.

“Barack Obama is as fine a writer as they come.”

Opening sentence of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s New York Times review of A Promised Land.

The most obvious reason Barack Obama was a different kind of president is that he is African American. The second reason Barack Obama was a different kind of president is that his id and his ego seem to have reached an accommodation decades before it became a matter of global consequence. The third reason Barack Obama was a different kind of president is that he is a writer, which is the main reason why A Promised Land is a different kind of presidential memoir; the most outsider-ish account in the genre of what it’s like to occupy the most powerful office in the world.

As with all firsts, the enormity of Obama’s breakthrough as the first Black president of the United States is easy to lose sight of given all that’s happened since. But from the moment in 2004 when Obama entered the political hive mind — through the portal of a soaring, unifying speech to the Democratic convention in Boston — as the man most likely to fill that role, it was the needle through which all other expectations, probabilities, obstacles and likelihoods had to be threaded.

And while the author himself downplays the role of destiny in what happened after that, the book reminds us of just how sublimely all of the elements, choices, twists, turns, reversals and key moments that made him president fit together.

To begin with, the decision Obama made to run when he did; it gave him the major advantage of being underestimated, because of his relative inexperience, by those with a proprietary attachment to the office. As the late Massachusetts “Lion of the Senate”, Ted Kennedy, told the freshman Illinois senator a little wistfully in 2006, “You don’t choose the time. The time chooses you.” In Obama’s case, the fact that the time seemed a little too soon was one of the things that made it his.

“So, my question is, why you, Barack? Why do you need to be president?” Michelle Obama asked during a decisive meeting in Chicago in December, 2006. It may have been a cry for help in rationalizing what would obviously be an unimaginably disruptive experience for a young family, but it produced the following answer: “I know that the day I raise my right hand and take the oath to be president of the United States, the world will start looking at America differently. I know that kids all around this country — Black kids, Hispanic kids, kids who don’t fit in — they’ll see themselves differently, too, their horizons lifted, their possibilities expanded. And that alone…that would be worth it.” What he didn’t say — because, as a normal guy he has a regulation-sized ego — was that millions of Americans and a few million more elsewhere, following the 2004 speech and, more resoundingly after the publication of The Audacity of Hope two months before that meeting, had already answered the question. And they might not have decided that the time had chosen Barack Obama if he’d been married to someone other than Michelle Obama, which made it — enormous sacrifices and all — her time, too.

The historic quality of Obama’s candidacy, enmeshed with his character, backstory, family and stated principles about a “different kind of politics”, produced a number of factors crucial to his ultimate victory, not the least of which the value-added self-selection of campaign advisors of a particular breed. Axelrod and David Plouffe — true believers in the unifying politics Obama espoused — could have easily signed on with other contenders ahead of 2008. The fact that they didn’t, and that they and Gibbs all saw something in Obama much bigger than the odds he was given in late 2006, produced the sort of campaign alchemy that made 2008 a once-in-a-lifetime election from not just from a historic perspective but for jaded pros whose faith in politics and democracy was renewed.

Full disclosure: In late 2007, I signed on to volunteer for the Obama campaign in South Carolina ahead of the upcoming January primary. Having lived in the US for nearly a decade and raised my daughter there until she was 10, I saw Barack Obama’s candidacy, as so many people did, as more than a longshot and, potentially, exponentially positive in ways that would impact not just America but the rest of the world. I spent three weeks in Obama campaign HQ in Columbia, watching those stated principles about a “different kind of politics” actually play out in every front-line decision taken on the ground, watching the internet used as a positive force for democratic engagement — including a grassroots fundraising operation that enabled the Obama campaign to compete against formidable war chests with help from millions of small donors — and witnessing the potent clash of tactical politics against hope and change as African Americans in the state overcame their fear of the former and skepticism of the latter with some stunning encouragement from a bunch of white people in Iowa. I was offered a national column by Sun Media to cover the rest of the election campaign while I was standing in “The Pit” at Obama HQ two days before Barack and Michelle Obama won the state in a landslide. I spent the next three years, including two in Washington, covering the story.

Obama prevailed in a nomination battle during which I ran out of synonyms for “grueling” — Homeric, Odyssean, Herculean, freaking epic — against doubt, against white racism, against protective Black fear for both his chances and his safety and, most of all, against a ruthless political machine that viewed him as an upstart interloper and whose misjudgment of both the candidate and the American people proved fateful. By the time Obama faced Republican war hero John McCain in the general, it was already the best US presidential campaign story since 1960.

Obama prevailed in a nomination battle during which I ran out of synonyms for “grueling” — Homeric, Odyssean, Herculean, freaking epic — against doubt, against white racism, against protective Black fear for both his chances and his safety and, most of all, against a ruthless political machine that viewed him as an upstart interloper.

That Obama is more well-adjusted than most presidents — a proposition impossible to separate from his status as the first Black president based on the difference between a monomaniacal need to be president for the power, and a recognition, based on the preponderance of evidence, that you could just be the first Black president — is clear throughout A Promised Land, mostly because its author spends far more time than most men, most politicians and, surely, most presidents, essentially asking himself whether he’s being a jerk. While his successor may have raised the absence of that sort of introspection to cartoonish levels, it’s a quality whose value in public service and damage control had also eluded previous presidents, to sometimes catastrophic effect.

Unlike so many political memoirs, this one doesn’t cast the author as the hero of every anecdote, and doesn’t use its word count to rationalize, revise or rewrite history to protect his reputational currency for posterity. The early post-inauguration section reads more like a report by an embedded journalist describing the fraught, stressful, frequently surreal, often wondrous daily existence of a normal president of the United States. Which is where the difference of being a writer in the Oval Office stands out.

“Given how hectic everything was in the first few weeks after I took office, I barely had time to dwell on the pervasive, routine weirdness of my new circumstances,” Obama recalls. “But make no mistake, it was weird.” That’s not a declaration written by someone finally reveling in the power, status and comfort of a job they’ve long considered rightfully theirs to assume once an assortment of obstacles, human and otherwise, are obliterated. It’s an observation written by a guy who wakes up in an exotic ecosystem of rituals, codes and protocols that, unless you have a less-than-healthy relationship to power, should feel weird. As Obama told the Washington Post, his memoir model was James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time, not conventional presidential autobiographies.

As the weirdness gives way to the routine of running the world, the rest of the book describes, among other challenges, the domestic and international economic policy mobilization undertaken to clean up the mess of the financial crisis and its aftermath, the foreign policy highlights from the Cairo speech to the first Beijing visit, to the first meeting with Vladimir Putin, to the famously consultative Afghanistan review. In between, there are the predictably unpredictable agenda-flouting detours from the bizarre arrest of African American Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. to the Underwear Bomber to the BP oil spill to the Somali pirates. And, of course, a chapter on the pitched, hyperpartisan battle for health care reform. The killing of Osama bin Laden in May, 2011, closes this first volume.

The predictable backlash — racist and political — against Obama’s presidency began before Donald Trump turned questioning his legitimacy into a cable cottage industry. It played out in Mitch McConnell’s adoption of the vow to keep him to a single term as a daily affirmation, among other tactical shrinkage projects. In A Promised Land, Obama frames Trump’s victory as a pendulum swing. “It was as if my very presence in the White House had triggered a deep-seated panic, a sense that the natural order had been disrupted. Which is exactly what Donald Trump understood when he started peddling assertions that I had not been born in the United States and was thus an illegitimate president. For millions of Americans spooked by a Black man in the White House, he promised an elixir for their racial anxiety.” The fact that Joe Biden, whose contribution as vice president Obama consistently praises in the book, has beaten Trump this time by more than 6 million votes may indicate that while the backlash element was a factor in 2016, there were other reasons Trump won.

More than that, when the “natural order” of politics includes a hierarchy of power based on special interests, entrenched biases and unwritten exclusions that maintain a particular status quo, exposing the vulnerability of that status quo to unexpected incursions by outsiders — especially outsiders promising and to a significant extent delivering both competence and socioeconomic justice — racism becomes not just toxic but doubly cynical as a Trojan Horse for interests seeking redress.

By the time Trump became president and launched a degradation campaign against democracy in general and America in particular, it looked less like a backlash and more like a vendetta. If you had designed a scheme to punish Americans for giving Barack Obama the first back-to-back majorities in half a century, it could not have been more precisely, thematically curated than Trump’s all-out attack on reason, truth, national unity, executive competence, international leadership, diplomacy, intellectual acuity, moral integrity and racial reconciliation. To say nothing of the hourly Trumpian rebellion against the Obama administration guiding principle of “Don’t do stupid sh*t.”

Frederick Douglass said, “Power never relents without a demand.” This time, the more than 80 million people who voted for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris have issued a demand that America make good on the promise of A Promised Land.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor of Policy Magazine and a columnist for The Hill Times. She was Washington bureau chief for Sun Media from 2009-2011, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP in New York and UPI in Washington.