The British Bulldog: Winston Churchill and D-Day

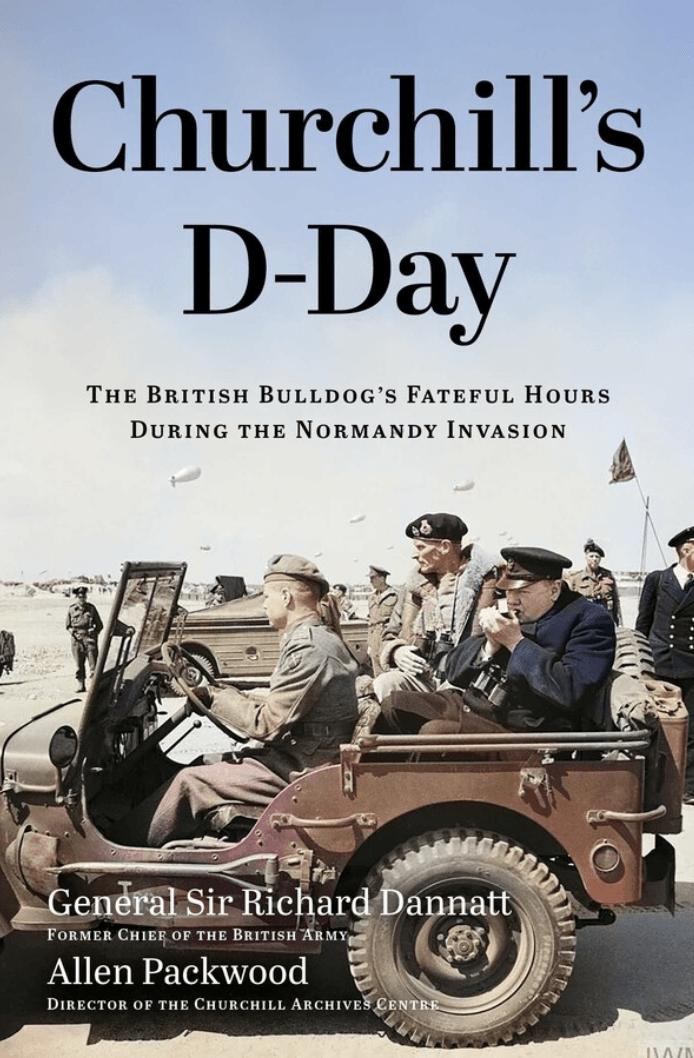

Churchill’s D-Day: The British Bulldog’s Fateful Hours During the Normandy Invasion

By General Sir Richard Dannatt and Allen Packwood

Simon & Schuster/Diversion Books/May 2024

Reviewed by Colin Robertson

May 20, 2025

On the night of June 5th, 1944, Clementine Churchill made her way to the underground Cabinet War Rooms near Downing Street in search of her husband. She found him in the map room amid a tumult of ringing phones, barked updates and palpable tension, hunched over the plans for the next day’s Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied France.

“Do you realize”, Winston Churchill said, “that by the time you wake up in the morning twenty thousand men may have been killed?”

Such were the enormous human stakes and burden of responsibility as Operation Overlord was about to be unleashed in the early hours of June 6, 1944.

When Churchill spoke to the House of Commons the next day, Labour MP Harold Nicholson described him as “white as a sheet.” Nicholson feared that he was “about to announce some terrible disaster.” Instead, Churchill would report to the House that the early hours of the Normandy landings had been a success. “There are already hopes that actual tactical surprise has been attained,” he said, “and we hope to furnish the enemy with a succession of surprises during the course of the fighting.”

D-Day is now seen not just as the tipping point in the Second World War, but as a turning point in global history. While the story has been told many times, including by Churchill himself, authors Richard Dannatt and Allen Packwood shed new light in their Churchill’s D-Day: The British Bulldog’s Fateful Hours During the Normandy Invasion.

The outcome of D-Day has become entrenched in the collective consciousness as inevitable but, as with every military victory, it depended on a number of things going right for one side and just as many going wrong for the other.

A career soldier, General Lord Dannatt served as Chief of General Staff (CGS), and Packwood is the Director of the Churchill Archives Centre at Cambridge University. Dannatt’s military expertise provides clear laypersons’ explanations of the preparation and planning of the massive operation. Packwood’s prodigious knowledge of all things Churchillian gives us new insights including letters, photographs and gleanings from original documents.

Their combined talents have produced a lively account that goes well beyond D-Day, taking us back to the lack of preparation before the war, then through the difficult early years when nothing was certain beyond the “blood, toil, tears and sweat” of hanging on against a formidable foe.

Colin Robertson’s Global Exchange interview with Allen Packwood

Over decades of hindsight, the outcome of D-Day has become entrenched in the collective consciousness as inevitable but, as with every military victory, it depended on a number of things going right for one side and just as many going wrong for the other. As Dannett and Packwood point out it, “it was not so easy, simple, and predictable.” In adding their account of the complex factors that came together to make D-Day successful — shifting political alliances, conflicting military strategies, evolving tactical needs, and huge logistical challenges — a “less confident, more confusing story emerges”.

The five landings were the most complicated and difficult military operation that had ever occurred. It involved an immense armada of over 4,000 ships and 11,000 aircraft and, by the end of August, more than two million troops from fifteen nations, including 14,000 from Canada.

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles landing at Juno Beach on D-Day/LAC

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles landing at Juno Beach on D-Day/LAC

That it succeeded is why, 80 years later, we are celebrating the allies’ victory in Europe and paying tribute to the venerable few who were part of that remarkable assault on the beaches on the Normandy coast. Canadian forces led the assault on Juno and then continued on to liberate the Netherlands.

Churchill’s D-Day focuses on a series of themes: the complexity of the operation, the use of deceptive measures to maintain the element of surprise and convince the Germans that this might be the first of several assaults, the challenges of developing unity of the American and British commanders, and the morale and training of the troops. All were essential for success but ultimately it depended on leadership, especially that of Britain’s wartime prime minister.

Indeed, Churchill, who with Franklin Roosevelt was one of the two greatest leaders produced by democracies during the 20th century, is at the centre of this story.

Churchill rallied Britain, the dominions and the empire in its “darkest hour” after the fall of France, when the seemingly insurmountable momentum of Hitler’s war machine could have toppled the free world into self-fulfilling despair. His words and actions personally inspired those who sought freedom everywhere. He set in motion the preparations that would culminate in Operation Overlord.

Churchill rallied Britain, the dominions and the empire in its ‘darkest hour’ after the fall of France, when the seemingly insurmountable momentum of Hitler’s war machine could have toppled the free world into self-fulfilling despair.

Churchill’s misgivings about launching the second front that Stalin wanted, and Roosevelt supported, were not unfounded. Churchill carried, fairly or not, responsibility for the Gallipoli debacle in 1915 as well as the failure at Dieppe in 1942, where 916 Canadians lost their lives. The invasions of North Africa and Sicily had confirmed the difficulties inherent in such amphibious operations.

By D-Day, the Allied effort was increasingly becoming an American-led show. Churchill — the realist — had recognized that the war could only be won with American participation even if it meant ceding them control. It was a quest Churchill pursued with vigor. Despite the dangers, he crossed the Atlantic three times abord the Queen Mary in his personal campaign to woo Roosevelt, recognizing the relationship with the United States and the commitment to Overlord as the “keystone arch of Anglo-American co-operation.”

At the same time, and despite his well-founded wariness about Soviet communism, he created the necessary accommodation with Marshall Stalin. “The enemy of my enemy is my friend” became the pragmatic foundation of a distrustful but mutually beneficial relationship. As Churchill put it to his private secretary, Jock Colville, “If Hitler invaded Hell, I would at least make a favourable reference to the Devil in the House of Commons.”

Democracy and the democracies are once again threatened by forces within and without. The story of D-Day and then VE-Day are a reminder that liberation once tyranny takes hold comes at a high cost. Nor can we be certain of having a Churchill at the helm.

But just as an American president is now proving how much damage to democracy one man can cause, this book reminds us that there once was a politician who used the power of personality to defend, not imperil, freedom.

Policy Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.