The China-Russia Tag Team of Turmoil

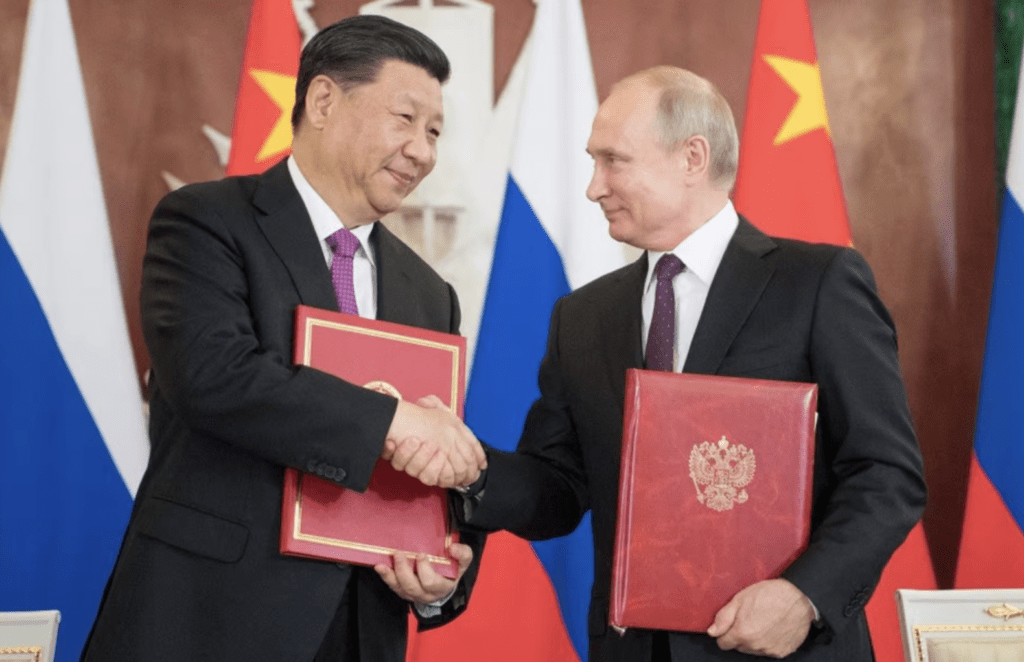

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin in Beijing, February 4, 2022/Xinhua

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin in Beijing, February 4, 2022/Xinhua

Lisa Van Dusen

April 5, 2022

When Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin declared their mutual admiration in a bilateral rendezvous hours before the Beijing Olympics opened February 4th, you might have been forgiven for processing the symbolism of that photo-op as that of equal partners conflating their dystopian brands for exponential impact.

In fact, the relationship between the Chinese president and his Russian counterpart is more akin to that of a McDonald’s CEO and a diffident local franchise manager, or, to adjust the metaphor for sanctions, a Teremok CEO and a diffident local franchise manager.

On that day, the two Wannabe World Order players issued a shot across the bow of the liberal, democracy-led global power status quo that left no doubt as to where Beijing stood on the issue of what Putin would do next, or, to clarify the question for context, what the 100,000 Russian troops then amassed on Ukraine’s borders would do next, or, more precisely, what those troops would do once the Olympics that were about to get underway wrapped on February 20th.

“Some forces representing a minority on the world stage continue to advocate unilateral approaches to resolving international problems and resort to military policy,” read the joint manifesto rationalizing Bond-villain world domination designs with far less compelling fiction, “they interfere in the internal affairs of other states, infringing their legitimate rights and interests, and incite contradictions, differences and confrontation, thus hampering the development and progress of mankind, against the opposition from the international community.” Fittingly enough for an anti-democracy cabal that specializes in scaled-up intelligence and propaganda operations, a fine specimen of tactical misdirection in every single item (the weaponization of projection as a propaganda tool in these circles has been a regular feature from the coining of “fake news” by a man who lied 30,000 times in office to Russia’s claim that Ukraine staged the trail of civilian corpses in Bucha and beyond).

That timely display of pre-mayhem unity in Beijing belied a subtext produced by two decades of operationally enabled narrative and cyberwarfare attacks on democracy from inside and out capped by an invasion of Ukraine based on no credible pretext other than to catalyze an endgame. China, not Russia, has been the senior geopolitical partner in that global campaign. (For more on the astonishingly frictionless operational trajectory of these events, see my previous pieces: While America…Seriously? on the intelligence community’s claim in January 2019 that it “slept” through China’s emergence as a threat to democracy; the ironic Can the Intelligence Community Save Democracy? from May 2020; and, from this January, Does the Intelligence Community Have a Conflict of Interest in the War on Democracy? on how maybe not everyone finds the prospect of a totalitarian surveillance state-based world order entirely resistible).

The relationship between the Chinese president and his Russian counterpart is akin to that of a McDonald’s CEO and a diffident local franchise manager, or, to adjust the metaphor for sanctions, a Teremok CEO and a diffident local franchise manager.

While the portrayals, in the days following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, of China’s “tight spot” and “ambivalence” on the merits of the unilateral approach of Putin’s resort to military policy beggar belief given both recent history and that February 4th statement of intent, they are a testament to the propaganda stylings of this lunacy. Since then, China’s own actions have clarified the truth about where it stands on unprovoked invasions, genocidal dehumanization and democracy degradation — a position that should surprise absolutely no one given the overwhelming preponderance of evidence.

Meanwhile, as the world observes the crimes against humanity unfolding in Ukraine, Beijing is leveraging Russia’s morbid content sphere monopolization and sudden displacement of China as the world’s number one threat to freedom to tie up some loose ends in its debt-trapped dependencies.

In Sri Lanka — which has been a guinea pig for Beijing’s exportation of anti-democracy norm obliterations since China enabled genocide as an approach to conflict resolution in the kettling and mass extermination of the Tamil Tigers in 2009 — the country’s simmering political tension has combined with economic turmoil to produce full-blown crisis. In a national degradation narrative that reads like an ACME replication kit of Venezuela’s descent into failed democracy/failed state status — from the China debt trap to the economic malpractice to the power outages and shortages to the avoidable human suffering to the constitutional crisis — Sri Lanka is now heading for the list of corruption-captured, engineered basket cases being operationally propelled into the “non-democracy” column of global freedom indexes.

Pakistan — long the model for democracies plagued by asymmetrical intelligence power — is also in constitutional crisis. Former cricket star Imran Khan, whose ascension to power in 2018 after 16 years in opposition telegraphed a sudden amenability to his statesmanship on the part of the influential Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), was removed in a non-confidence vote on April 9. In this case, Khan’s enthusiasm for China and Russia makes his political ouster and the country’s constitutional crisis an outlier in the international pattern of Beijing’s Faustian, amenability-for-permanent-power approach. China agreed last week to roll over Pakistan’s $4.2 billion debt during the same regional governments meeting in Tunxi at which it publicly declared its longstanding proprietary interest in Afghanistan. For more on these developments, we go to the regional expertise of Shishir Gupta in Monday’s Hindustan Times with Pakistan and Sri Lanka face political turmoil fueled by Chinese debt and Prabhash Dutta for India Today on Monday with Sri Lanka and Beyond, a Chinese hand that feeds crisis.

The global war on democracy that became so flamboyantly overt with the previously imponderable degradations of the Trump presidency has been defined by neither geography nor ideology. It has been defined by power consolidation via industrialized deception in narrative after narrative across datelines and continents. What’s happening in Ukraine is crucial to the geopolitical goals laid out in Beijing by Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. It is also crucial to the goals of interests elsewhere enthralled by the lure of power conveniently unfettered by democracy.

Lisa Van Dusen is associate editor and deputy publisher of Policy Magazine. She was Washington/international affairs columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News, and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.