The Generational Change in War and Remembrance

So many Canadians grew up with fathers and grandfathers whose Second World War service remained acknowledged but never discussed. But the long-term effects of witnessing the horrors of battle are now addressed more openly, treated more effectively and borne with less shame. As Elizabeth Moody McIninch writes, now we just need the government to step up for the veterans who risked their lives for Canada.

Elizabeth Moody McIninch

“Just don’t get maudlin about serious things, Liz. Like the war.” I was nine years old and off school for a few days to go with my dad on a sales trip to Medicine Hat, Alberta. That meant don’t ask questions on our road trip about things best kept in the past. I didn’t get maudlin and neither did most of my generation. We stayed the course as the horrors of battle faced by our fathers hummed like an electrical charge in the air between us. As we drove across the prairie on that trip, I did not ask, “What did you do in the war, Daddy?”

Because we couldn’t see our fathers’ invisible wounds, we thought they were fine. They looked fine. Think of the wedding pictures so many of us cherish. Not until many decades later did the families of veterans start to talk about the emotional trauma so many of them tried to hide. We didn’t think about things like night terrors, unexplained, profound sadness, and heavy drinking. Those angry outbursts were just, well, better forgotten. It was all glossed over.

If ignorance was bliss, then we lived in a perfect world.

At the dawn of this century, our cultural relationship to the memories of war and the burden they represent for soldiers, for veterans and for their families changed. The Croatia Board of Inquiry published its report into the horrors faced by Operation Harmony, the Canadian peacekeepers who had served in Croatia during the rampage of Slobodan Milosevic across the former Yugoslavia.

In September of 1993, OpHarmony was caught between the Serbian and Croat front lines in the “Medak Pocket”, coming under heavy fire trying to prevent the hell of ethnic cleansing, including mass executions and torture. After they secured the area, their task was to catalogue the atrocities for the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in preparation for war trials.

It took six long years before the inquiry got down to business. Many of the returning heroes from the Balkans were sick. The belief was that contaminated soil in the abandoned industrial sites where they were working was the cause of their invisible wounds. The inquiry called hundreds of witnesses. Many of them tried to say the sickness was imaginary. To make matters worse, the old school argued that because this was not real combat, these peacekeepers did not deserve pensions.

As the testimony went on, the frightening reality of the debilitating symptoms became clear. A nation listened. The issue was not contaminated soil. Our soldiers were not sick because of the environment but because of their nightmarish experiences in the Balkans theatre. A whole new level of understanding was born on the long-term impacts of battlefield trauma and the post-traumatic stress disorder experienced by so many soldiers.

The distinguished military historian, Allan English, wrote about the paradigm shift at the Department of National Defence (DND) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) under pressure from a Canadian public angry over how Croatia veterans had been treated.

In “From Combat Stress to Operational Stress: The CF’s Mental Health Lessons from the Decade of Darkness” (2012), he argued that the report “… drew public attention to the shameful way Canada treated its wounded personnel suffering from physical and mental wounds. … The adoption by the CF of the term ‘Operational Stress Injury’(OSI) to encompass a wide range of mental health issues, and to reduce the stigma associated it with mental illness … represents the progress made in identifying these issues.”

The age of recognition that operational stress injuries could be highly destructive to military and veterans’ families was upon us. It was a reckoning for many. Aided and abetted by the silence of our fathers, my generation had let the echoes of similar, undiagnosed trauma fade away.

My father only put pen to paper about the crash of his Consolidated Liberator GR V1 EV881 in Wales, in September 1944, when a young man named Jonathan Teasdale had learned about the Liberator memorial at Carn Bica, and wrote to him in 1988 along with two of the other survivors.

There had been a reunion of 547 Squadron in London in 1987. Before it took place, I drove my parents up to the crash site in Wales. It had to have been a traumatic moment for my father. The wheels turned — I saw it in his eyes. It was time to tell his story.

Back in Toronto, he wrote up his recollections to a young aviation enthusiast he had never met. Strange, in a way. His family had never heard them before.

A Survivor’s story.

When a young, slight, fair-haired Canadian lad named Edward John (Ted) Moody started training in the Bahamas with the R547 squadron in the latter months of 1943, he was able to take some confidence in the prediction that the Allies would win the war.

Swift to Strike was the squadron motto; the insignia, the Diving Kingfisher, was a vivid depiction of the role played by airmen in the furious battles the Allies waged against the German U-boats in protection of convoys critical to the survival of Great Britain.

The Battle of the Atlantic, in which Canadians played a critical role, was won, but at great cost. More than 70,000 Allied seamen, merchant mariners and airmen lost their lives, including approximately 4,400 from Canada and Newfoundland. And then there was Bomber Command. Forty percent of Canadian aircrew were posted to the 6th group. They suffered staggering losses. In early 1942, the chance of surviving a single tour was 44 percent and only 19.5 percent of surviving a second. During the Battle for Berlin in the latter months of 1943, the casualty rates were about 60 percent. Carnage in the skies.

No matter where our airmen served, they lived daily on the brink between the living and the dead. If they cracked from stress, they were met with RAF psychiatric diagnoses such as Lack of Moral Fibre (LMF), a policy meant to shame airmen back into their aircraft by removing their rank and privileges. (For a brilliant treatment of the period, Allan English’s 1996 book, The Cream of the Crop: Canadian Aircrew, 1939-1945, from McGill-Queen’s University Press, or, for a great journalist’s take, read Dave McIntosh, Terror in the Starboard Seat, Stoddart Publications, (2002).

Permission to wear their hard-won flying badges could be revoked. Service documents might be marked with the dreaded large red “W” for waverer. As national indignation swept through the then-Dominion, the government finally granted commissions to all Canadian aviators. Attempted removal of flying badges was brought under the control of the RCAF.

Canadians were having none of it. Logic, pure talent, and a love of flying was the Canadian way. Aces from World War 1 went on to open up the Far North as bush pilots. In 1939, the RCAF launched the British Commonwealth Air Training Program, training thousands of Commonwealth crews for the duration of the war.

Aviation was something we just did well. As Cliff Adams, historian to the legendary 418 squadron in which my father served during the post-war years, told me:

“Canadians at the time in aircrew always looked distinctively Canadian and a bit less formal than RAF counterparts. The top button on their tunic was always undone and they always had their hands in their pockets for photos. This drove the RAF types crazy. They had no sense of decorum, these Canucks, no respect for authority. They were savages, debauched colonials!”

My dad’s story, as recounted in John Evans’s Final Flights: Aviation Accidents in West Wales. From the Great War to the 1990’s, Vol. 1, fit very well with Cliff’s impressions:

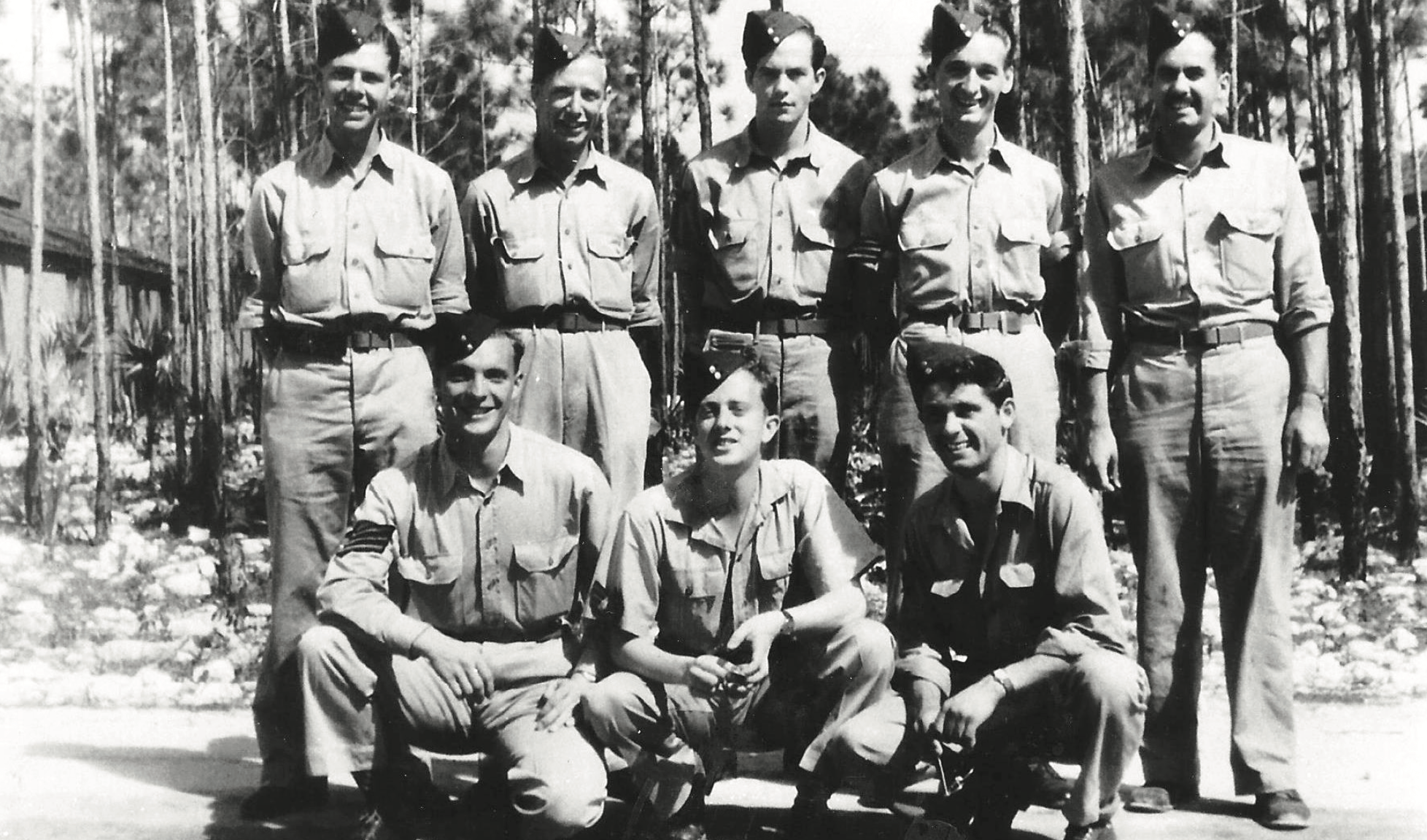

“Our crew was probably a typical bunch of guys from such places as Saskatchewan, Quebec, Surrey, and Yorkshire…but having been thrown together in the RAF, we had an incredibly close relationship…We had chosen our crew in Nassau, the Bahamas, and were determined to prove that a bunch of NCOs (non-commissioned officers) could hack it with the commissioned ranks any day of the week…We were full of beans and quietly confident we could take on anyone our size or larger…We were all in the same billets, mess and were virtually inseparable from then on.”

After being trained on B-25 Mitchells in the Bahamas, the tight-knit team flew to St. Eval, Cornwall, and began the transition to the Consolidated Liberator, which had become, because of its long range, the best anti-submarine aircraft in the war.

It also became known, unofficially, as the Flying Coffin.

On the night of September 19th, 1944, dad’s crew was called out to practice with the new Leigh Light anti-submarine searchlight in an exercise with a Royal Navy submarine.

As my father recalled: “I was listening out on the radio to group frequency with my back to the front of the aircraft. The radio operator’s position had a large metal seat and was well padded —possibly the combination of these two factors helped to save my life. All of a sudden, there was an incredible explosion when we hit the mountain. … When I came to, my clothing was starting to burn and my hands and hair were starting to sizzle…I thought I heard crying in my semi-conscious state but learned later it was sheep maimed by the crash.” When they hit Carn Bica in the Presili Hills they were carrying 1,500 gallons of gas. They were only a few feet too low.

There were three survivors, all of them badly burned. Six crew members died. These were the most important people in my father’s life at the time. They had been inseparable. As I started my own journey of remembrance, I thought of how dad looked sometimes. Detached. Kind of disassociated with what was going on. We know so much more now about the link between PTSD and, among other symptoms, dissociative episodes.

What kept aircrews flying against intolerable odds? Research has shown that their biggest fear was letting not just their country but their comrades down — a sense of not just patriotic but personal valour. In some ways, that meant more than life itself. No bond was closer, said Cliff Adams. The heroism of these crews was remarkable.

I asked Cliff about his recollections of symptoms of PTSD in the squadron at that time. He replied:

“Many of the WWII aircrew personnel had grave doubts about their survival and that manifested itself in several ways – alcoholism, abject fear (hence LMF — Lack of Moral Fibre), almost suicidal behaviour … Each person I’ve talked with about their wartime experiences had a different reaction to their time of service. Many would merely ‘clam up’ and refuse to talk about their experience. A few would admit to fear but most would mention some of their happier experiences and refuse to dwell on the more terrifying ones.

By 1952, my dad was back in the air again. He flew with the 418 (Edmonton) Squadron as tensions with the then-Soviet Union were becoming the Cold War. Operating from historic Blatchford Field, he and his mates flew B-25 Mitchell medium bombers training to defend the Canadian North.

There wasn’t any help for our heroes then, but there is now.

For over two decades, the Veterans Transition Network (VTN) has been helping military personnel transition to civilian life, to deal with their trauma in a confidential and non-threatening way.

Connecting with former identities, or taking the big adventure to creating a new one is tough when your world has been turned upside-down. In a special message to returning Afghanistan veterans, Dr. Paul Whitehead, the Clinical Director of VTN wrote: “If you are … angry and frustrated about recent events, you are not alone… It’s not just you… You don’t need to manage trauma alone.” Their inspirational stories are told on their website, vtncanada.org, also a worthy fund-raising page.

Isolation, homelessness, and despair are the lot of too many of our veterans. We need to look into the millions of dollars wasted in lawsuits over disability and pension claims and the millions more left on the books by our governments, past and present. We need to speak up in favour of veterans who have had to sue for their claims; the number of families thrust into poverty, waiting for their claims to be processed. Think about it: disabled veterans suing the same government they protected with their lives.

The Liberal government recently announced they are only extending the contracts of one-third of the temporary staff hired to deal with a backlog of over 34,000 claims. Lawrence MacAulay, Minister of Veterans Affairs, had to admit under questioning in the House recently that the average veteran has to wait at least 40 weeks for their claims to be heard.

When my 15-year-old grand-daughter, Jane Estephan, asked for my help with her history project recently, I was delighted to know she was learning about the First World War and the Canadians who served. Jane wrote her story about a 21-year- old dentist who had been slaughtered in the first wave at the Battle of the Somme in 1916

“What did they make them do that for?”, she asked, with tears in her eyes. I choked up.

“We should visit his grave in France,” she suggested. “Yes,” I said, “that we will do.”’

My father passed away in 1995, but for my family, the site of his crash on a hilltop in Wales remains a sacred place. Remnants of the Liberator can still be seen there. The Pembrokeshire Aviation Group built a memorial to honour the crew, living and dead. The fire at the site was so fierce, the grass at Carn Bica never grew again.

Contributing Writer Elizabeth Moody McIninch is a business consultant who served as archivist for the Rt. Hon. John N. Turner, Canada’s 17th prime minister.