The Liberal-NDP Deal: Making Minority Government Work

Reuters

Reuters

Robin V. Sears

March 29, 2022

Sanna Marin is the prime minister of Finland, presiding over a five-party coalition. She has pushed through a 2035 deadline for Finland to hit zero emissions, one of the toughest in the world – not a small achievement given that she must govern with four other parties. The Finns today represent the most complex parliamentary democracy governing structure in the world.

At the other end of the spectrum is the United States, with the Democrats currently governing, but able to pass legislation or have appointments approved only by a tie-breaking vote in the Senate. Not surprisingly, the atmosphere is hyper-partisan and usually gridlocked. The opposition GOP can behave as irresponsibly as they think their base will enjoy, knowing this can rarely win any legislative victory – unless you include blockage and delay.

In between sit most of the democracies of the world, with at least two parties sharing power most of the time. There is no political cultural secret or mystery about this. It’s arithmetic. If you have more than three parties you will often have no one winning a majority of the seats. So you can either govern week by week with every major bill potentially triggering an election, or you can find some other arrangement that saves voters having to choose a new government every 18 months. That is the average length of a minority government in Canada. Consider: in the 1960s we had four elections, again in the 2000s, and another four since then. This is neither more democratic nor more accountable. It is simply irritating, expensive and ineffective.

Now, fans of the sword-of-Damocles approach to minority management can point to some dramatic legislative successes while governing under the threat of daily collapse: PetroCanada in the ’1972-’74 minority; our new flag in 1965. But the big achievements are increasingly fewer and farther between.

Add to this a federal state with highly distributed – sometimes conflicting – powers between governments that delivers an immutable reality about governing. It is very slow to find consensus, and very bad at long term-planning. Add to that shaky federal government, and little that is not short-term and/or urgent gets done.

Officials in a minority government have a nearly impossible task pushing through major policy changes that require extensive public consultation, multi-ministry approval, and lengthy cabinet and then parliamentary consideration. They know they will run out of runway before another election and then have to start all over again. Major issues like carbon taxes, pharmacare or cannabis legalization need years from conception to delivery.

So, given our two realities – a semi-immobilized federal state and unstable minority governments most of the time – what is to be done? To this former participant in, and observer of, every type of governing structure in our system, the answer seems obvious: an agreement between two or more parties to a four-year Parliament, with a signed public policy agenda, pledged to be delivered in that time frame.

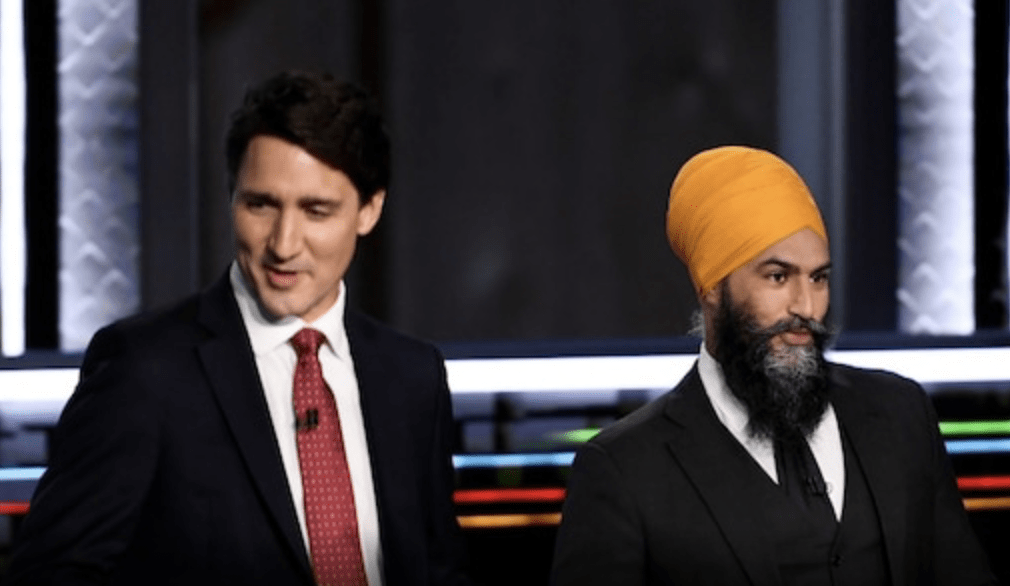

Kind of like what was announced by Jagmeet Singh and Justin Trudeau this month.

Now, political pundits nearly always default to the partisan risks, wins and losses in such deals. They give little attention to the policy impacts. With a deeply cynical view of the political arena, the horserace and the potential for partisan treachery, they discount on Day One any motive or outcome that includes big policy achievements. They selectively pick from historical examples to ‘prove’ that the smaller party always loses and that the larger party always double crosses and rarely delivers. Tell that to Bob Rae or John Horgan, and they will smile indulgently.

There is no political cultural secret or mystery about this. It’s arithmetic. If you have more than three parties you will often have no one winning a majority of the seats.

Canadian voters have very little permanent partisan attachment anymore. An enormous block of us float between being Blue Liberals and soft Tories, between being Liberals by default much of the time, but checking their tendencies by occasionally supporting New Democrats, too. Such was the case in Ontario in 1985, when Rae’s NDP supported David Peterson’s minority Liberal government that ended more than four decades of Conservative rule. And in British Columbia in 2017, Horgan’s NDP governed in their first term without even a plurality of seats, having 41 seats in the legislature to the Liberals’ 43, but able to defeat Christy Clark’s incumbent government on a confidence vote with the support of the Greens and their three seats. Invited to form a minority government by the lieutenant-governor, Horgan was returned to office with a majority in 2020. In Alberta today, provincially, the switchers are traditional centrist Tories leaving Jason Kenney’s hard-right United Conservative Party for Rachel Notley’s moderate New Democrats, astonishingly.

Pierre Poilievre’s seemingly suicidal strategy for rebuilding the Conservative party is to rally his base of maybe 10-15 percent hard core right-wing Tories, hoping that the other half of the Tory base will hold their noses at his hyper-ventilating rhetoric and remain loyal. Doubtful, and in any event, a guaranteed loser’s strategy.

There is an old aphorism in Asian politics about doing a deal with your opponent; “He who rides the tiger is afraid to dismount”. Various versions of this aphorism are used to predict the certainty that the New Democrats will get eaten by the Liberal tiger one of these days. But unpacking this a little reveals its weakness as a prediction.

Given most voters’ willingness to slide a little to the left or right in their ballot choice, with most of us having little hard-core party loyalty, let alone party membership, how do we choose whom to vote for? The leader is a key vote motivator. In other words, is the candidate a package one might label, “prime ministerial?” It includes voters’ assessments of authenticity, likability, credibility, competence, and experience in governing. The British have a lovely term for the winner of such a contest. They have “broad bottom” appeal.

The success of these kinds of deals depends very much on the trust built between three key pairs: the leaders, their chiefs of staff, and the House leaders.

Assuming Trudeau retires after three terms and a decade in office in 2025, Singh will be going into his third campaign as the most experienced leader in the field. He will face a new Liberal leader likely as shaky under attack as nearly every freshman leader is. He may face Jean Charest, which would make his task complicated, since Charest is also a veteran and a very compelling campaigner. But should he face Poilievre, presumably by then a 45 year-old adolescent, however, his odds would improve considerably.

In that case, Singh will have “bottom”, having helped to govern and deliver popular policy achievements on health, housing and climate change over the previous three years. If he is betrayed by the Liberals during the governance agreement they will face two risks: being slammed for once again promising and not delivering, and seriously damaged credibility about anything they promise for the future. If they try to claim credit for the big changes delivered, Singh can merely observe they had promised them all for years and not delivered. What changed? An NDP whip.

The success of these kinds of deals depends very much on the trust built among three key pairs: the leaders, their chiefs of staff, and the House leaders. All three will need to be keen caucus managers: good trouble spotters, good listeners, and good healers after the inevitable collisions. The Liberals have those qualities in two of the three positions, the prime minister will need to learn the names of all his MPs and work from there. The NDP are well served in each role, and it appears that they have developed good relations with their opposite numbers in each case.

When struggling to find a path to such an agreement there are three “tells” about the likelihood of success — both reaching a deal and making it work. The first is absolute secrecy in the discussion phase. Each side blew that in their first round, and then successfully screwed the lid down tight on any leaks this time. The second “tell” is how long the process takes, and how long and how productive is each round of talks. Too short, and you end up with a disaster such as the Lib/Lab coalition under David Cameron and Nick Clegg in the UK. They attempted to negotiate a formal coalition — the hardest type of cross-party deal — from a Friday morning to a Sunday night. Too long and you know one of the parties, at least, is not serious.

When the news emerged that Singh and Trudeau had spent more than three hours together in the final round of talks at Rideau Cottage, it revealed a good relationship, a willingness to take big risks, a determination to get it done, and a respectful approach to bargaining.

Brian Mulroney likes to remind incoming leaders that you don’t leave any legacy in high office if you focus on trying to conserve your political capital, you must spend it to achieve success. Jagmeet Singh and Justin Trudeau have both put a lot of their political capital at risk. For Canada’s sake, we should wish them well.

Contributing Writer Robin V. Sears is a former national director of the NDP during the Broadbent years. He now works in Ottawa as an independent consultant specializing in crisis communications.