The Making of a Minute: Norman Kwong’s Field of Dreams

A scene from the Norman Kwong Heritage Minute shoot/Historica Canada

A scene from the Norman Kwong Heritage Minute shoot/Historica Canada

By Anthony Wilson-Smith

April 7, 2024

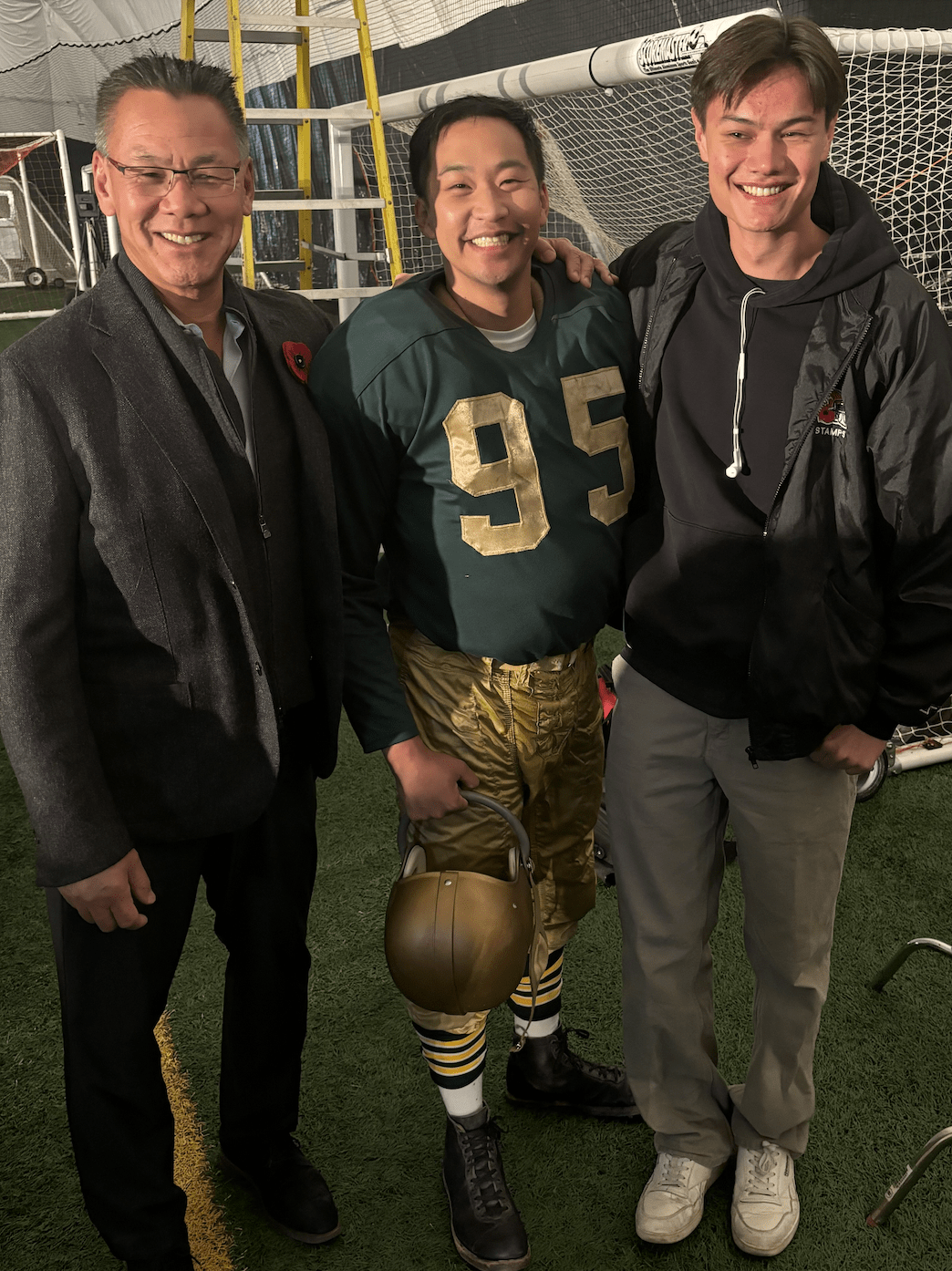

Even with an early-morning mist dulling the glow from the overhead lights, Greg Kwong figured he knew what to expect when he and his son, Brendan, strode onto a football field of dreams at Calgary’s Macron Centre one morning last November. But as he later confessed, nothing could have prepared him for the sight of the figure approaching him – a player suited-up in a 1950s uniform, grinning in anticipation, with the number 95 imprinted in gold on his dark green sweater — the number Greg’s father, Norman Kwong, had worn as an all-star Canadian Football League running back.

“Hey, Dad,” Greg said to actor Patrick Kwok-Choon, who was playing Norman Kwong in the Heritage Minute devoted to Kwong’s role as an athletic diversity pioneer. Then, the two hugged. “It was,” an emotional Greg Kwong later recalled, “surreal.”

Sometimes, such is life in the making of the iconic Heritage Minutes, produced by Historica Canada, the non-profit organization of which I am president, and funded principally by the federal Department of Canadian Heritage. Most of the time, the highest levels of drama take place within the carefully scripted 60 seconds of each production. But every now and then – as with the making of this most recent Minute – real life emerges from the sidelines to steal the show.

The Heritage Minutes highlight people and events who in some way helped shape the Canada in which we live today. In recent years, we have increasingly tried to tell stories about Canadians of all manner of backgrounds who fit that definition. We chose Kwong because, as the first professional Chinese-Canadian football player – one who came of age when overt racism was commonplace in his hometown of Calgary, as in many places across the country — he possessed all the bravery and spirit that can sometimes make ordinary people make history. In Kwong’s case, that meant simply playing a game at which he was exceptionally skilled as though stereotypes didn’t matter, as though systemic racism was no obstacle, and as though daring to engage in physical combat over a football with predominantly white opposing teams was not a flagrant challenge to the status quo.

Kwong persevered against the odds, the racism, the preconceived expectations, and still holds a string of Canadian Football League rushing records. After retirement from football, he became, among other things, part-owner of the Calgary Flames hockey club at the time they won their only Stanley Cup to date, and served from 2005 to 2010 as Alberta’s lieutenant-governor – the first Asian-Canadian to hold the role. In short, he was by any measure a person of remarkable achievement. Kwong died in 2016 at age 86.

To Greg and his three brothers, and the whole Kwong family, Normie Kwong was ‘Dad’; his on-field glory having played out when they were either not yet born or were too young to recall. The grainy, black-and-white footage from the era seems, as it is, far removed from present. As well, Normie Kwong was reluctant to boast to his children about his experiences. “Dad steered away from it,” says Greg, himself a pillar of Calgary’s business community.

As is often the case, producing this Minute was a reminder that the past can seem at once very far away, yet timely as well. Calgary in the 1930s was overwhelmingly white. Chinese people coming to Canada, like Kwong’s parents, paid the equivalent of almost $17,000 each in today’s dollars because of what was known as the federal ‘Chinese Head Tax’ levied uniquely against people coming from that country. Discrimination was overt: employers often refused to consider Chinese applicants; the prejudice was both official and cruelly casual (such as the graffiti displayed in the Minute adding “or Chinese” to a “No dogs allowed” sign). Normie Kwong established his toughness through routine wins in fistfights with neighbourhood bullies.

Today, Calgary, like the rest of Canada, is much different. The 2021 census showed that more than four of 10 Calgarians are non-white. Naheed Nenshi, who is on our Historica Canada board and served 11 years as Calgary’s mayor (the first Muslim elected to the position in any big city in North America in 2010) says that there are entire neighborhoods where “a child can grow up and go right through to the end of high school and quite possibly never meet a Canadian-born white classmate.”

Challenges persist. As with all our recent Minutes, we advised production companies interested in working with us that in addition to on-air talent, we expected key creative positions such as director, director of photography and writer to be filled from within the specific community featured. The Chinese-Canadian team members had some modern-day stories to tell.

Greg Kwong, Patrick Kwok-Choon, Brendan Kwong

The always-affable Kwok-Choon, playing Norman, has built a successful career on both sides of the North American border, with notable roles that include the recurring character of Gen. Rhys on the CBS science fiction drama Star Trek: Discovery. But growing up in Montreal, he faced challenges that helped him relate to Kwong. “Like him, my parents ran a convenience store,” he said. “And like him, I encountered my share of direct racism. So, the chance to tell a related story of perseverance and success was irresistible.” The Toronto-based director Yung Chang, a multi-award winner in Canada and the United States for his documentaries, saw this project as very personal. “I have young children,’ he said, “I want them to see a Canadian hero to whom they can really relate.’

This was also the first Minute we have made about a very longstanding and familiar institution – the Canadian Football League – and we knew we would face a demanding crowd coast-to-coast-to-coast in terms of loyal fans of the nine CFL teams.

To recreate a specific game — the 1955 Grey Cup — we had to match the uniforms worn then by Kwong’s team, the Edmonton Eskimos (known today as the Elks) and their opponents, the Montreal Alouettes. Our production partners, Barbershop Films, found or created appropriate uniforms from the era, including old-style single-bar helmets. The extras serving as players in game scenes were made up largely of former university players, along with several former CFL players. Director of photography Alan Poon shot scenes in close-up and slow motion to emphasize the controlled violence of every play, with a fog machine and dimmed lighting lending an appropriately surreal air looking back in time.

The work of recreating a 1930s corner store – another key part of this Minute – was challenging in ways requiring near-maddening precision. Working inside a long-standing general store in a Calgary suburb, the team removed modern-day items like coolers and furniture and replaced them with period pieces. They bought cases of tinned vegetables and fruit, peeled off the labels, and replaced them with replicas of 1930s products. (After the shoot, the unopened tins went to a local food bank.) They printed copies of a period newspaper with genuine articles inside, including one referring to the “China Clipper” – one of Kwong’s nicknames. The casting team found the veteran actor John Dylan Louie, who along with his considerable acting chops brought the necessary fluency in Chinese to the role of Norman’s father.

The completed Minutes you watch on any one of a variety of screens are indeed only 60 seconds long – but they take up to nine months of preparation and production, start-to-finish. That includes the RFP (Request for Proposal) process to choose a production partner, the usual necessities of casting, script preparation, location scouting – and very intensive historical research. Unlike other film or television productions that may say at the outset “Based on a true story”, we try to come as close to the true story as is possible. Our characters were all real, living people; the characters’ lines are wherever possible historically authenticated (drawn from diaries, historical records or similar stories), and our researchers are so meticulous that something as seemingly trivial as the colour of a button on a uniform can spark heated debate. There’s a devotion to dramatizing the lives we chronicle as respectfully as possible, and that respect is often expressed through a commitment to authenticity.

The shoots themselves are relatively quick – seldom more than two days. As with other productions, each scene is shot many times, often from different angles, to give as much latitude as possible in the final edit. Because 60 seconds is a really short time in which to tell a full story, we always have to leave a scene or two we loved on the cutting room floor. In the case of Norman Kwong, the loss that hurt most was a scene in which Kwong took a vicious hit from several opposing tacklers on a line plunge. After the whistle, as they glared at him, he gave them a smirk that said “Is that all ya got?”’ It was a great tribute to Kwong’s character, but in the end, we thought a scene of a younger Kwong interacting with his parents conveyed a more essential message about the forces that shaped him.

We wound up the shoot at the end of November, and our cast and crew dispersed back across the country to the various places in which they are based. Many of us, including director Chang, Patrick Kwok-Choon and other key figures, reassembled for a launch party at Calgary’s Chinese Cultural Centre in early February, marking the start of Asian Heritage Month. It was a gala affair sponsored by First National Financial – the company run by our Historica chair, Stephen Smith, and by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. It was hosted by Naheed – well before he launched his campaign for the leadership of the Alberta New Democratic Party – and included representatives of all three levels of government – and, of course, Greg Kwong and other members of the family. Within days, we knew we had a hit on our hands, based on hundreds of thousands of views on our social media platforms, and heavy exposure on both traditional and digital media.

The Minutes, launched and sponsored by the great philanthropist Charles Bronfman, will mark their 35th anniversary in 2026. When he explained his motivation at the outset, Charles – still a very active member of our Board – said this: “Every country has its myths and legends – but in Canada, no one was telling their stories.” His concern then was that young Canadians in particular were lacking the pride that comes with knowing their country’s past achievements. Today, that challenge continues – and is further enhanced by the need to cast a light on our past to the millions of new Canadians who continue to arrive from around the world. As they struggle to find their place and pride in their new land, they look particularly for inspiration to the stories of those who came before them. In the story of Normie Kwong, and others in our catalogue of Minutes, we hope they find both inspiration and hope.

Anthony Wilson-Smith is president of Historica Canada and former editor of Maclean’s.