The Man Behind the Myth: An Intimate Biography of John Turner

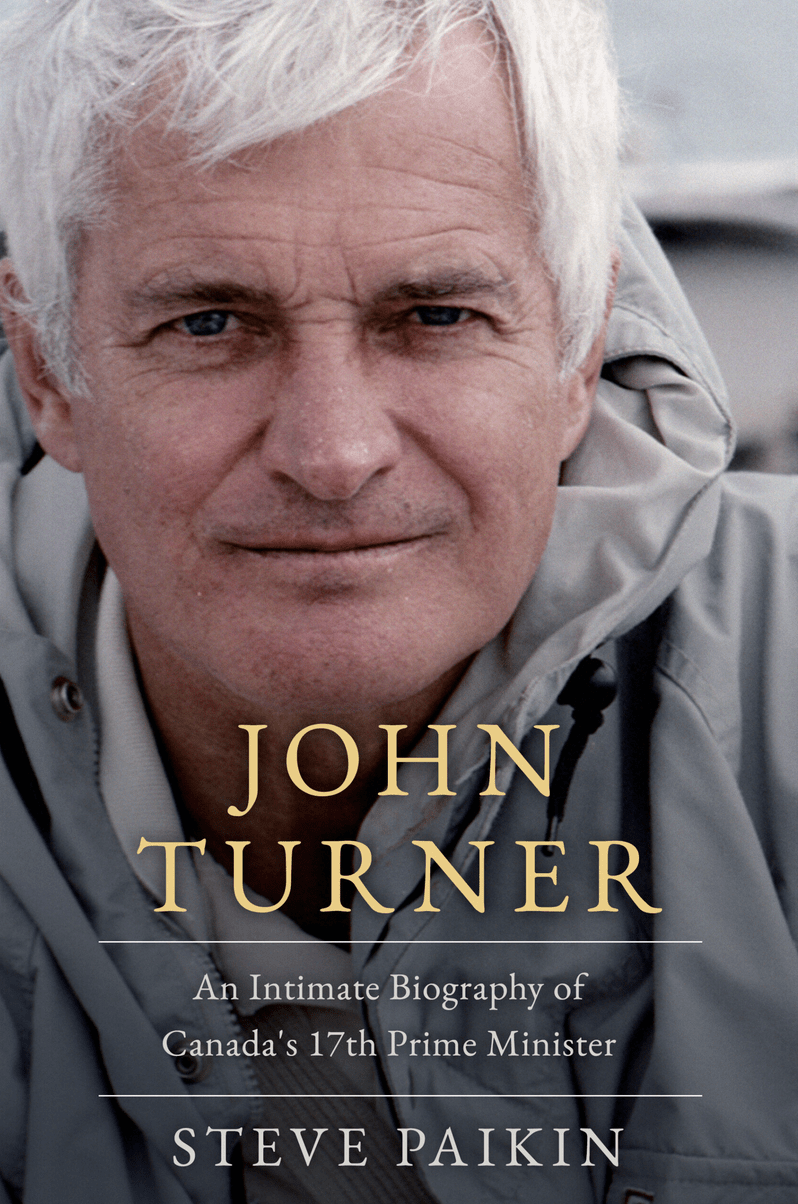

John Turner: An Intimate Biography of Canada’s 17th Prime Minister

By Steve Paikin

Sutherland House Books/October 2022

Reviewed by Bill Fox

September 18, 2022

The story of John Napier Turner, Canada’s 17th prime minister, is a story of expectations – on the part of his family, on the part of his political party, on the part of the country. Expectations largely unmet, in the minds of many.

Yet, in this “intimate biography”, author Steve Paikin makes a compelling case that Turner’s was a “life of consequence.” A life of outsized achievements and equally outsized disappointments. A life of privilege and duty. A life of faith buffeted by fate.

As Paikin so skillfully records, even the manner of Turner’s passing was otherworldly. The global pandemic denied Turner the tribute he deserved. Strict restrictions were imposed on the number of people permitted to gather at his funeral mass. Hymn singing was forbidden. And, as was the case so often in his life, the sniping didn’t end with Turner’s death. Some obituaries made a point of leading with the fact that Turner led the country for only 79 days, or 11 weeks — a petty, discretionary proof point as to why readers have less and less time for legacy media.

Paikin’s portrayal of Turner is at once more considered and more complete.

The biographical building blocks are set out in Paikin’s work – the Olympic-calibre sprinter, the Rhodes Scholar, the dashing man about town with the matinée-idol good looks who dated a royal princess. As are the predictions of success: a mother who once said of her son, “If he can’t be prime minister, he can always be pope”; a young Montreal lawyer named Brian Mulroney who, in the early 1960s, told a friend, “He’s going to be prime minister someday.”

Even these retellings benefit from Paikin’s exceptional access to Turner, with whom the host of TVOntario’s public affairs program The Agenda was in regular contact over the years. That access continued posthumously — to Turner’s family, including his wife Geills, his surviving children, his closest associates and the treasure trove of papers Turner and his entourage had kept. The result is storytelling that rings with authority and authenticity.

Paikin takes readers behind the highlight reel of Turner’s political life and shares the details that put in context the stories so familiar to the politically engaged of Turner’s time.

Paikin provides key insights into Turner’s character — as a young parliamentarian on vacation in Barbados, he rescued former prime minister John Diefenbaker, who was struggling to free himself from a dangerous undertow — and didn’t tell anyone the story. How, at the height of the October Crisis in 1970, Turner told his wife, “If I ever get kidnapped, don’t let anyone pay a ransom.”

Readers are reminded of Turner’s singular accomplishments as Canada’s first minister of consumer and corporate affairs, as the justice minister who carried through Pierre Trudeau’s decriminalization of same-sex relationships and abortion, as a successful minister of finance who balanced budgets, but whose most cherished title was “Member of Parliament”.

The work is unsparing in Paikin’s analysis of areas where Turner was less successful — his failure to keep pace with an ever-evolving political agenda, his curious acceptance of the intrigue that is an inherent component of partisan policies, his unawareness of advancements in social norms. It was never appropriate for a male to pat a female colleague on the derrière; it was politically fatal to do so on camera in 1984.

Paikin points out that Turner’s political instincts when he assumed the Liberal Party leadership in 1984 weren’t as sharp as they needed to be on other issues. Shrugging off traditional Liberal support for linguistic minorities as a matter best left to the provinces was staggeringly ill-considered. The outgoing Trudeau’s offer to take the heat for a series of excessive patronage appointments should have been accepted. And forsaking the opportunity of a summer of photo opportunities with Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth and the Pope in favour of an election call was a political miscalculation that puzzles to this day.

The author is equally candid about key elements of the Turner’s persona – his fondness for certain four letter expletives or a glass of scotch. As Paikin states, “His use of blue language at unexpected moments was both hilarious and wildly inappropriate.”

Turner knew Canadian politics had to pivot from the rights-focused discourse of the early 1980s inherent in constitutional reform and patriation to an economic focus. And he knew full well Canada was in a mood for change.

Paikin deals directly with the issue of Turner’s relationship with his wife Geills, who wasn’t always seen by critics as helpful to Turner’s political career — critics, as Paikin notes, who insisted on applying a conventional political-partner frame to a person who had spent her life defying convention.

Turner, perhaps surprisingly, did struggle with his self-confidence on occasion, according to Paikin.

But the irony of John Turner, politician, is that Turner himself foresaw many of the shifts in public opinion that would lead to many of his political disappointments.

Turner knew Canadian politics had to pivot from the rights-focused discourse of the early 1980s inherent in constitutional reform and patriation to an economic focus. And he knew full well Canada was in a mood for change.

Turner’s time as Liberal leader was largely defined by two accords. And Turner’s positions on both put him in direct conflict with powerful factions within the Liberal Party.

Turner’s support for the Meech Lake constitutional accord and his opposition to the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement were positions of conviction, and not electoral convenience as some assumed at the time. History suggests Turner was more right than wrong on Meech, arguably more wrong than right on free trade, in both instances at significant political and personal cost.

Turner’s uneasy relationships with both his predecessor, Pierre Trudeau, and his successor, Jean Chrétien, is a key theme of Paikin’s work.

Turner was subjected to a level of disloyalty from his own party leadership that will leave readers slack-jawed in amazement. Turner was told repeatedly by individuals he had put in positions of authority that he simply had to go. Paikin carefully chronicles how Pierre Trudeau refused to take the stage in a show of unity when Turner was elected party leader in 1984, how then party president Iona Campagnolo emboldened dissidents at the same convention when she declared leadership rival Jean Chrétien “second on the ballot but first in our hearts”. The shocking coup that wasn’t quite a coup launched against their own leader by Liberal strategists at a key moment in the middle of the 1988 campaign is both treachery and farce.

The former Liberal leader’s staccato-like speaking style was deemed ill-suited for the “cool” medium that is television. Yet Turner’s televised leaders’ debates with Brian Mulroney in 1984 and 1988 are the stuff of legend. Each enjoyed a pivotal moment. Each knew what it was to personally shift momentum in a national campaign. Each came away with a respect and appreciation for the other. Mulroney, who as Canada’s 18th prime minister would succeed Turner, described his political adversary as “a gallant warrior and a very worthy opponent,” a view shared by many who had the good fortune to work on Parliament Hill during Turner’s time. Paikin records this respect and appreciation was not always shared by many Liberals.

On his return to private life, Turner had to listen to a lot of “the man didn’t measure up to the myth” type of commentary, a man who wouldn’t or couldn’t adjust. Paikin asserts Turner was able to rise above the descriptive as the “King Lear” of Canadian politics, and quotes the former prime minister as saying, “I couldn’t have asked for more, I deserved a good deal less.”

Paikin, like his friend the historian Arthur Milnes, declares a passion for a better understanding of politics, politicians and history. In “John Turner: An Intimate Biography of Canada’s 17th Prime Minister”, Paikin succeeds admirably on all counts.

Bill Fox was Washington and Ottawa bureau chief for the Toronto Star and press secretary and director of communications for Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. He is currently a fellow in the Riddell Graduate Program in Political Management, Carleton University. His latest book, Trump, Trudeau, Tweets, Truth, A Conversation, is available now from McGill Queen’s University Press.