The Many Electoral Faces of Québec

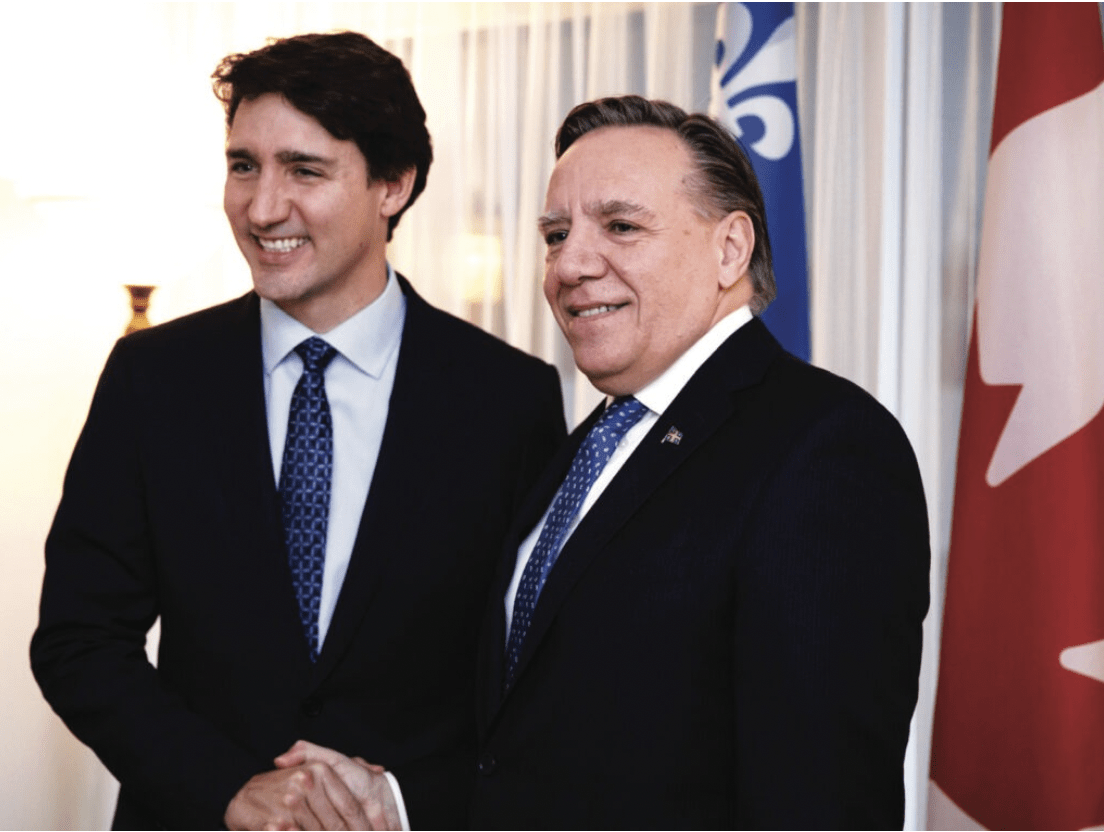

Adam Scotti

Adam Scotti

By Daniel Béland

February 15, 2024

In an interview with Canadian Press last month, Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet complained about what he saw as the emergence of “two Quebecs”: Montreal and the rest of the province. According to Blanchet, Montreal is “a city at best bilingual, possibly multilingual, in an extremely passive manner in which the history, the language, values and the culture of the very generous host society are becoming marginalized.” This is why the rest of Quebec, he added, “looks at Montreal as if Montreal is in the process of becoming a foreign place.” For Blanchet, this is a bad thing because Quebec “should be one culture, one nation, with all its diversity. That’s what Quebec is. And we are getting away from that.”

Although these statements reflect the nationalistic views of the Bloc leader, the sense that Montreal and the rest of the province are growing farther apart is widespread in Quebec, a perception exacerbated by some signature policies of the Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), especially Bill 21 on secularism and Bill 96 on language policy, which have been received much more critically in Montreal than in the rest of the province. Yet, when we look closely at the federal electoral map of the province, this dichotomy between Montreal and the rest of Quebec does not tell the full story.

First, as political scientist Jean-François Daoust points out in response to Blanchet’s statements, there are at least two Montreals: the more anglophone, western part of the island, and the more francophone eastern part. Historically, Saint-Laurent Boulevard served as the unofficial division between these two parts of the city, which have evolved over time but remain clearly distinct demographically and, therefore, electorally. On the western part of the island, the large anglophone population has long been associated with the Liberal brand, which is why Liberals are dominant there both provincially and federally.

In contrast, in the much more francophone eastern part of the island, the Liberals face much more electoral competition. At the provincial level, Québec Solidaire and, even further east, the CAQ, are strong. At the federal level, the only NDP seat left in the province is located in the eastern riding of Rosemont—La Petite-Patrie, where MP Alexandre Boulerice remains popular despite the disintegration of the 2011 Orange Wave at the 2015 and 2019 federal elections. Further east, in the La Pointe-de-l’Île riding, Mario Beaulieu is currently the only Bloc MP on the island on Montreal.

Yet, just like Jack Layton’s NDP won many seats on the island of Montreal back in 2011, when the orange wave hit the entire province, under the leadership of Gilles Duceppe, the Bloc used to hold several seats on the island. In fact, Duceppe was the MP of the central-eastern riding of Laurier-Sainte-Marie from 1990 to 2011, when he was defeated by Hélène Laverdière from the NDP, who was re-elected in 2015 but defeated by Liberal Steven Guilbeault in 2019.

The example of this riding illustrates the reality that the Liberals are not as deeply rooted in the eastern part of the island as they are in the western part, where many ridings have been “solid red” for decades. This is why, at the next federal elections, Liberals are likely to be vulnerable only in several ridings located in the eastern part of the island. At the same time, it is not sure whether the Bloc or even the NDP could capitalize on this situation. As for the Conservatives, the island of Montreal is not an area of the province where they would be expected to make significant grains or even win a single seat.

With the exception of the vague bleue of Brian Mulroney in 1984, Conservatives do struggle in Quebec in general, as they only won 10 seats in the province in 2021. The situation of the Conservatives is more favorable outside of Montreal but even there, as with the island, the rest of the province is not a homogeneous entity, electorally speaking. For instance, within the rest of the province, the greater Quebec City area (Capitale-Nationale and Chaudière-Appalaches) is well-known for its distinct political culture and electoral patterns, both at the provincial and at the federal levels. One of the most dynamic economic regions of the country, this area is more conservative on average than other parts of the province. This is why the CAQ is currently dominant in the greater Quebec City area at the provincial level, and why the Conservatives have most of their 10 Quebec seats here at the federal level.

At the next federal elections, the Conservatives could try to win more seats in the greater Quebec City area, especially in ridings they held in the recent past. These ridings include Beauport-Limoilou and Beauport-Côte-de-Beaupré-Île d’Orléans-Charlevoix.

Even if he speaks French relatively well, Poilievre is perceived as an outsider by many francophone Quebecers. As for anglophones located mainly in the Montreal area, they’re not in the habit of voting Conservative at federal elections.

If the Conservatives want to win significantly more seats in the province than in 2021, however, they will need to win more seats outside the greater Quebec City area, which is a tall order, as the Bloc is dominant in most of the ridings the Conservatives would normally target. For years now, the Conservatives have told Bloc voters that they should vote for them because only they can get rid of Justin Trudeau and his government. This strategy has not paid off yet, perhaps because the Trudeau government is not nearly as unpopular in Quebec as it is in some other provinces. This might be related to the fact that Prime Minister Trudeau is a resident of Quebec and an MP in the Montreal riding of Papineau. In contrast to both Trudeau and Blanchet, Pierre Poilievre is clearly an outsider, which is partly why the Conservatives have stressed the fact that his wife Anaida was raised in Pointe-aux-Trembles, a francophone neighbourhood located on the far east of the island of Montreal.

Regardless of the region of Quebec, however, the fact that Poilievre is not a Quebecer is a clear disadvantage for him when facing Blanchet and, to a lesser extent, Trudeau. Even if he speaks French relatively well, Poilievre is perceived as an outsider by many francophone Quebecers. As for anglophones located mainly in the Montreal area, they’re not in the habit of voting Conservative at federal elections. Because of this, the Conservatives are mainly targeting francophone Bloc ridings located in the rest of the province.

Based on geographical and historical voting trends, the Belle Province remains quite challenging for the Conservatives, even if recent polls suggest that they have significantly improved their standing in Quebec. In this context, the Conservatives hope to increase the number of seats they win in the province but they are likely to only target the parts of the province identified above as having growth potential, so they’re unlikely to waste precious resources on the island of Montreal. As for the Liberals, they will play defence, especially outside of Montreal and the diverse suburb of Laval, the third-largest city in Quebec, where the Liberals have controlled its four seats since 2015.

Outside of the province’s largest city and its largest suburb, the Bloc remains in a strong position and the main foe for both the Conservatives and the Liberals. The fact that the Bloc only runs a campaign in Quebec rather than across the entire country like the other major federal parties gives it a clear advantage. At the same time, as the 2011 Orange Wave suggests, the Bloc is hardly invincible in francophone Quebec, a situation that gives hope to Blanchet’s opponents and forces him to remain aggressive in his attacks against the federalist parties.

Like any other province, Quebec is hardly homogeneous and the outcomes of the next federal elections in the province will largely depend on the capacity of the major political parties to adjust their strategies to the different regions that comprise this vast territory. Once again, in Quebec as elsewhere, all politics is local, and thinking of the province as a homogeneous entity or even as a world centred on a simple dichotomy between Montreal and the rest of the province is problematic. In our electoral system, each riding is a separate electoral entity, and the area of the province in which the riding is located matters enormously. This is why political analysts and strategists focus on key local and regional differences within each province instead of living in a world of generalizations.

Contributing Writer Daniel Béland is Director of the McGill Institute for the Study of Canada and James McGill Professor in the Department of Political Science at McGill University.