The New Minority Parliament: No ‘Build Back Better’ without Change

Kevin Page with Jiayu Li and Xuan Liu

“Build back better” has become a catchphrase for political leaders around the world since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy thinkers at international organizations like the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggest it is about creating a socioeconomic environment in the wake of two global crises (2008 and 2020) that is more equitable, sustainable and resilient.

Building back better was a central theme of the 2021 Canadian federal election. No surprise. A public health crisis has a way of exposing the cracks in society.

Metrics of income and wealth inequality are expected to deteriorate. We can already see the divergences in high-wage versus low-wage employment rates in the pandemic recovery. De-carbonization is not easy. Notwithstanding the economic shutdowns to slow the spread of the virus, it looks like Canada will barely make a dent in its greenhouse gas emission trajectory in 2020. COVID-19 gave our health care and long-term care systems a serious beating. Healing will require more than just rest.

If building back better is the goal, how can political leaders and policy makers use the light from the cracks to take us to a more equitable, sustainable promised land?

Students of logic argue that it is essential to think of both necessary and sufficient conditions for an event to occur (i.e., building back better). Necessary conditions must be present. Sufficient conditions are the conditions that will produce the event.

We see two necessary conditions for a build-back success. Number one: political cooperation. Number two: a credible fiscal plan. The sufficient conditions include the combination of the right priorities and policies with enhanced public confidence and trust. Nobody should think that the goals of build back better are easily attainable.

Hard choices and limited pay-offs is how Paul Wells, in the post-election edition of Maclean’s, describes the political calculus of the current policy environment. “The very best that can be said for election campaigns,” he writes, “is that they obliterate any hope of such conversations for only five weeks.” With the 2021 election results in the rearview mirror, the challenges of governing are real and present.

Since 1867, we have had 15 minority governments, five of which have emerged within the last 20 years. Typically, in life, practice makes things better.

Political analyst Robin Sears made the case in Policy Options in 2009 that two things separate the relatively weak legislative performance of recent minority parliaments from the stronger performances of minority governments in the 1960s and 70s. One, there are strong working relationships across party lines between senior figures in each party. Two, there is recognition that legislative victories are shared.

Political scientists who study the science of game theory would applaud those astute observations. Political bargaining situations can be examined through a number of common elements: players, interdependencies, differences of interests, rules of progress and methods of enforcement.

In the 44th Parliament, we have some of the conditions that would favour political cooperation.

Political leaders are well known. Interdependences are high with strong regional representation of different political parties. In this environment, we cannot make national progress without multi federal party support and cooperation with others levels of government and the First Nations’ peoples. Minority governments can fall on votes of confidence. While all political parties wish to increase their electoral chances in the next election, the actual differences of policy interests are smaller than many might think.

Chart 1 highlights the priority and policy complementarities across the governing and opposition parties. This is true—not just among the Liberals, NDP, Greens and Bloc—but, between the Liberals and Conservatives as well. In theory, this should help, not hinder political cooperation. The political risks of hard policy choices and limited pay-offs can be better managed with broad support and cooperation.

Do we have the leaders with the foresight to work across current political divides and put the long-term interests of the country first on the big policy issues such as improving our social safety net, addressing climate change and preparing our country for the next policy shock whether it be health, climate or financial?

Take notice of the latest efforts by former Liberal and Conservative cabinet ministers (Anne McClellan and Lisa Raitt) who have teamed up with an impressive group of advisors including former Bank of Canada deputy governor Carolyn Wilkins and created the Coalition for a Better Future. We need this renewed spirit of coalition to be contagious. The government’s Budget 2021 commitment to launch a national infrastructure assessment is another opportunity to work across party lines.

Given the complementarity of priorities and policies, would there ever be a better time to develop media and civil society oversight to incentivize cooperation and accountability? American author Ta-Nehisi Coates has said it’s the job of activists to generate and apply enough pressure on the system to affect change. “Vision without implementation is illusion” to quote author Walter Isaacson. Without change, there is no build back better.

Governments of advanced economies around the world are shifting from fighting the pandemic to supporting the recovery and transforming their economies. While economic and fiscal outlooks are clouded with pandemic related uncertainty, the IMF and OECD latest analyses indicate that debt-to-GDP ratios appear to have stabilized and will remain persistently higher (some 20 percentage points on average) over the medium term.

The Canadian economic and fiscal experience has largely mirrored that of other advanced economies during the pandemic.

In Canada, the fiscal buffers (i.e., declines in debt-to-GDP and carrying cost of debt) largely created in modern times by prime ministers Chretien and Martin in the 1990s and early 2000s proved to be indispensable in saving livelihoods and lives in the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. Unlike many advanced and developing economies, Canada does not face an immediate and sharp trade-off between helping people and businesses in the recovery versus rebuilding fiscal buffers for the next crisis. Prime ministers Harper and Trudeau also deserve credit in holding the line on the debt-to GDP ratio in the period between the crises.

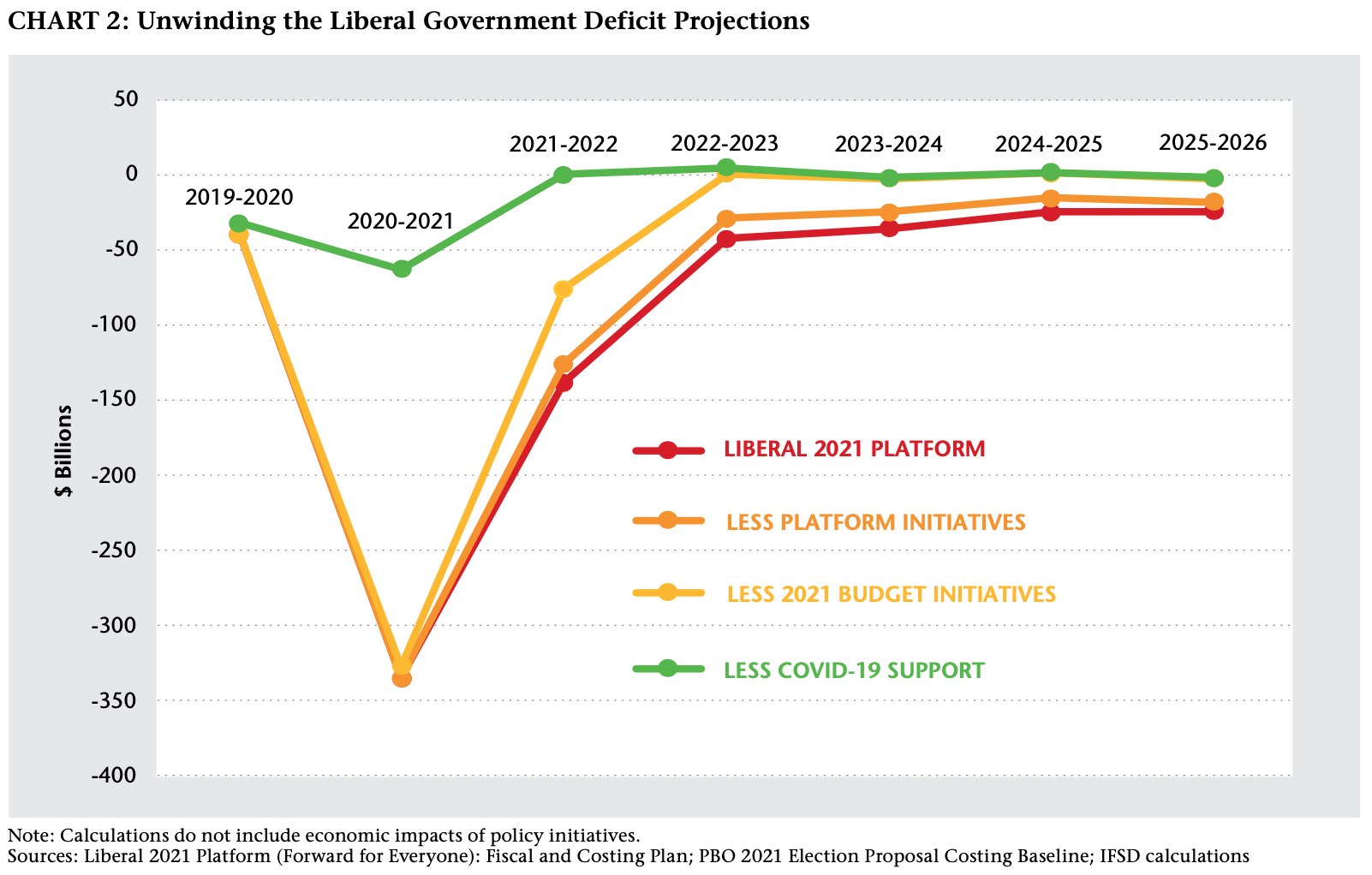

Chart 2 highlights the enormous swing in budgetary balances over the pandemic period and the projection to a more modest and sustainable budgetary deficit over the medium term. How does the deficit go from about $40 billion in 2019-20 to about $340 billion a year later and then return to about $40 billion per year over the medium term? The answer can be traced largely through the historical COVID-19 fiscal supports and the downs and ups of revenues linked to the strength of

the economy.

So, what is the strategy for financing the recovery and post-COVID structural reforms and maintaining or rebuilding our fiscal buffers for the next unexpected policy shock? How will we balance the downside risks related to the pandemic versus the upside risks related to structural reforms that will strengthen economic productivity and labour force participation? Like political cooperation, we see a strong fiscal plan as a necessary condition for a successful build back better outcome.

The IMF defines fiscal credibility in terms of public confidence in the capacity of the government to carry out its policy commitments while meeting its debt obligations at reasonable cost.

Table 1 highlights the planned fiscal path of the government over the medium term assuming implementation of its 2021 election platform and the Parliamentary Budget Office election baseline economic and fiscal assumptions. Fiscal headline numbers are moving in the right direction—declining budgetary deficits and debt-to-GDP ratios; a normalization of spending and revenue shares; and low carrying costs of debt.

To enhance public and bond market confidence, we need to see these headline numbers embedded in a fiscal strategy and plan. These numbers need to be set out as targets or anchors that get adjusted only by unexpected events like a public health crisis. A strong fiscal planning framework should guide political cooperation. More spending will be needed in a true build back better plan. In a stronger economic environment, we want the government and opposition parties to bargain over tax increases and spending reductions to finance additional public policy improvements so we can ensure appropriate fiscal space for the next generation.

Contributing writer Kevin Page is President and CEO of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa. He was previously Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer.

Jiayu Li and Xuan Liu are undergraduate economic students at the University of Ottawa.