The Revenge of the Phillips Curve

Douglas Porter

April 1, 2022

Pretty much all of the free world—okay, the financial world—was focused on the inversion of the 2s10s Treasury curve this week, and what that may portend for the economic outlook. We dig deeply into that very topic in this week’s Focus Feature, and the skinny is that the ominous message can’t be ignored, but this particular move does come loaded with caveats and asterisks. And it’s worth reinforcing exactly how we got here in the first place—two-year yields have rocketed by 170 bps since the start of the year, as the market scrambled to readjust to a Fed that is scrambling to keep up with inflation. That’s the fastest rise in a quarter (plus a day) for twos since the early 1980s, and simply blew away a nearly as impressive 90 bp surge in 10-year yields. The much bigger story than the inversion in parts of the curve is the complete reset of the entire curve.

But March’s U.S. jobs report and the Euro Area’s inflation release highlight a different inversion—CPI versus the jobless rate—which may carry an even bigger message for policymakers and helps explain that rate reset. With headline CPI in Europe jumping to 7.5% y/y in March—highlighted by Spain getting dangerously close to double-digit terrain at 9.8%—Euro Area inflation is now higher than its unemployment rate (6.8% for February) for the first time in decades. The crossover is even more extreme in the U.S., and not brand new, with the jobless rate tumbling to 3.6% last month, compared with 7.9% headline CPI inflation (or 6.4% on the PCE deflator, for purists). U.S. inflation moved above the unemployment rate last August for the first time since 1990, and the gap looks set to get even wider—we look for the March CPI to pop well above 8% in the coming release (due April 12).

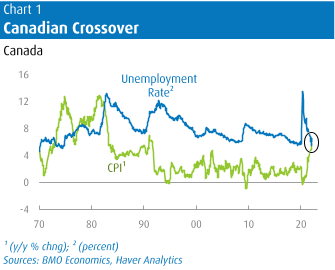

This economic inversion has also spread to Britain (inflation 6.2%, jobless rate just 4.4%) and, yes, to Canada as well. In February, Canada’s unemployment rate tumbled to close to 50-year lows of just 5.5%, while the inflation rate famously surged to 30-year highs of 5.7% (Chart 1). Little remarked on at the time of these releases, this was the first time since June 1982 that the Canadian inflation rate was higher than the unemployment rate. Such a crossover had been mostly a feature of the economy through much of the prior high-inflation decade.

Not every major economy has seen this inversion, as Japan, Australia, Sweden, and a variety of members of the euro are not there yet. That’s either due to still-low inflation (Japan), or high unemployment (Greece, Spain, Italy, France, Sweden). But even economies where inflation is traditionally very low have also succumbed to the crossover, with Switzerland’s headline inflation rate pushing just above the nation’s low 2.2% jobless rate, while Germany’s figures are remarkably close to the U.S. extremes (at 7.6% on CPI, and a 3.1% harmonized jobless rate).

Besides perhaps offering bragging rights in an economics trivia contest, what’s the implication of this seemingly quirky crossover in inflation and unemployment rates? Simply put, it’s a loud signal that policy has been far too loose for far too long, which was aimed—openly—at running the economy hot. Well, hot is what we got, with inflation at multi-decade highs and unemployment at multi-decade lows in some cases. For much of the past decade (and arguably the two before that), many analysts suggested that the Phillips curve and its underlying theory that there was a clear-cut tradeoff between job markets and inflation was a relic of a bygone era. Apparently not.

Monetary policymakers have received the signal loud and clear and are ramping up the urgency of their messaging with every passing week. In tandem, we have also been steadily upgrading our official view on how fast and how high short-term rates will rise. Following a fusillade of hawkish comments last week, we bumped up both our Fed and BoC calls. We now look for both to hike rates by 50 bps at each of the next two decisions, with the Fed hiking by a total of 200 bps in the next six meetings and then another 50 bps in 2023 to 2.88% (50 bps higher than we had before), while the Bank hikes 150 bps through the remainder of this year and also another 50 bps next year to finish at 2.50% (also 50 bps higher than we had before). In both cases, policy will get to the low end of neutral quickly, and then eventually move above the mid-point of neutral—a necessary step to douse inflation.

Inflation pressures are now so intense that they require an all-hands-on-deck policy response. In other words, this is not just a job for central banks. One could question the particular policy weapon of choice, but President Biden’s move to release 1 million bpd from the petroleum reserve for the next six months is a nod in the right direction. And the move did play a role in cutting oil prices $15/barrel this week to below $100, even as OPEC+ essentially stuck to the status quo with a piffling 432,000 bpd increase in output for the month. Arguably, China’s various lockdowns—now Shanghai—played a bigger role in slicing oil prices, but dislocated markets need work on both the demand and supply sides to bring them into better balance (see Canadian housing).

But fiscal policy also has an important role to play in helping to control inflation. After all, last year’s mega U.S. stimulus package is arguably what sent demand into the stratosphere, driving far beyond what global supply chains could handle, and providing households the wherewithal to readily pay up for price increases. Fiscal policy, thus, also now needs to take a long look in the mirror and stop adding to the inflation fires.

That’s an important message with Canada’s federal budget coming on Thursday. Some have asserted that inflation is mostly a global problem, and its roots in Canada can scarcely be blamed on domestic economic policy. But, just as the Bank of Canada has little choice but to now tighten policy, and tighten relatively aggressively, the same logic applies to fiscal policy. Alas, it appears that Canadian fiscal policy is still headed in the opposite direction. At the provincial level, it’s tough to discern a clear trend from the eight budgets on hand, but the overall theme has been one of surprisingly ambitious spending. Even provinces that are attempting to calm inflation are doing it with measures that could work at cross purposes (e.g., handing out money, not to put too fine a point on it).

At the federal level, we look for some big dollops of spending as revenues are coming in much stronger than expected on raging commodity prices. A decision to broaden and amplify social programs amid a commodity boom and ratcheting inflation is a very unfortunate throwback to the 1970s. (For dry historical purposes only, you understand, we will note that the great inflation of that decade just happened to be unleashed amid a Liberal minority government in Ottawa, supported by the NDP from 1972 to 1974.) The end result of such a tilt in fiscal policy is likely to be an even tighter job market and even stickier price pressures—accentuating the unusual inversion of unemployment rates and inflation. In turn, this will simply put the onus squarely on the Bank of Canada to carry the baton on the inflation fight, putting even more upward pressure on short-term interest rates in the year ahead.

Doug Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.