The Role of Energy Transition in Addressing Climate Change

Umer Farooq and Kevin Page

August 4, 2022

The global policy debate on addressing climate change has many dimensions, likely none more important than energy transition – improving energy efficiency and reducing the carbon intensity of our energy production systems.

To better understand the factors that govern global CO2 emissions it is helpful to use a relatively well-known mathematical relationship known as the Kaya identity. It is an identity introduced in 1995 by Japanese economist Yoichi Kaya. The formula has been used by climate and social scientists around the world. Its mathematical form is:

CO2 emissions = Population x (GDP/Population) x (Energy/GDP) x (CO2 emissions /Energy)

It says that the rate of change of CO2 emissions can be traced to population growth, per capita economic activity (an expression of standard of living), energy intensity (use of energy in production of goods and services) and the carbon intensity of our energy systems (the carbon content of our energy use).

From a policy perspective, the Kaya identity is simple, daunting and prescriptive. Identities are simple in that they equate expressions in algebraic terms (left side equals right side). The Kaya identity is daunting because it reminds us that reducing emissions involves fundamental constructs of our societies – demographics, well-being, and energy. It is prescriptive because it helps us focus our efforts – energy transition.

A highly skilled energy labour force and a proven technology track record are strong assets to drive continued progress in transition. The workforce in the Alberta oilpatch or in the nuclear industry of Ontario, as examples, are more than capable of being trained in green energy technologies.

Latest estimates suggest Canada’s total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions were about 730 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, excluding land use, land use change and forestry. To be frank, on a global scale, we are not a big part of the problem. Canada’s emissions represent about 1.5 percent of global emissions.

On a per capita basis, Canada looks less favourable. Herein lies the moral dilemma. We are the 10th largest GHG emitting country. According to the International Energy Association (IEA), Canada’s economy has the second highest carbon intensity among IEA members after Australia. CO2 emissions per unit of GDP were .32 kilograms of CO2 per US dollar, which is 70 percent above the IEA weighted average of 30 countries. We must do better. Canada’s credibility needs to be strengthened.

Canada has responded by setting ambitious targets and has brought forth significant policy changes and public investments. At the 2021 Leaders Summit on Climate hosted by the Biden administration, Canada announced its GHG target of 40-45 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and re-affirmed its net-zero by 2050. Significant policy changes were announced in 2016 (i.e., Pan Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change) and in 2020 (Strengthened Climate Plan) with total ongoing investments in the $100 billion range, relatively larger on a GDP and per capita basis than the US Climate Plan now being debated in Congress.

The production and use of energy in Canada accounts for about 80 percent of the country’s total GHG emissions. We need energy transformation – innovation, efficiency and growth of renewables.

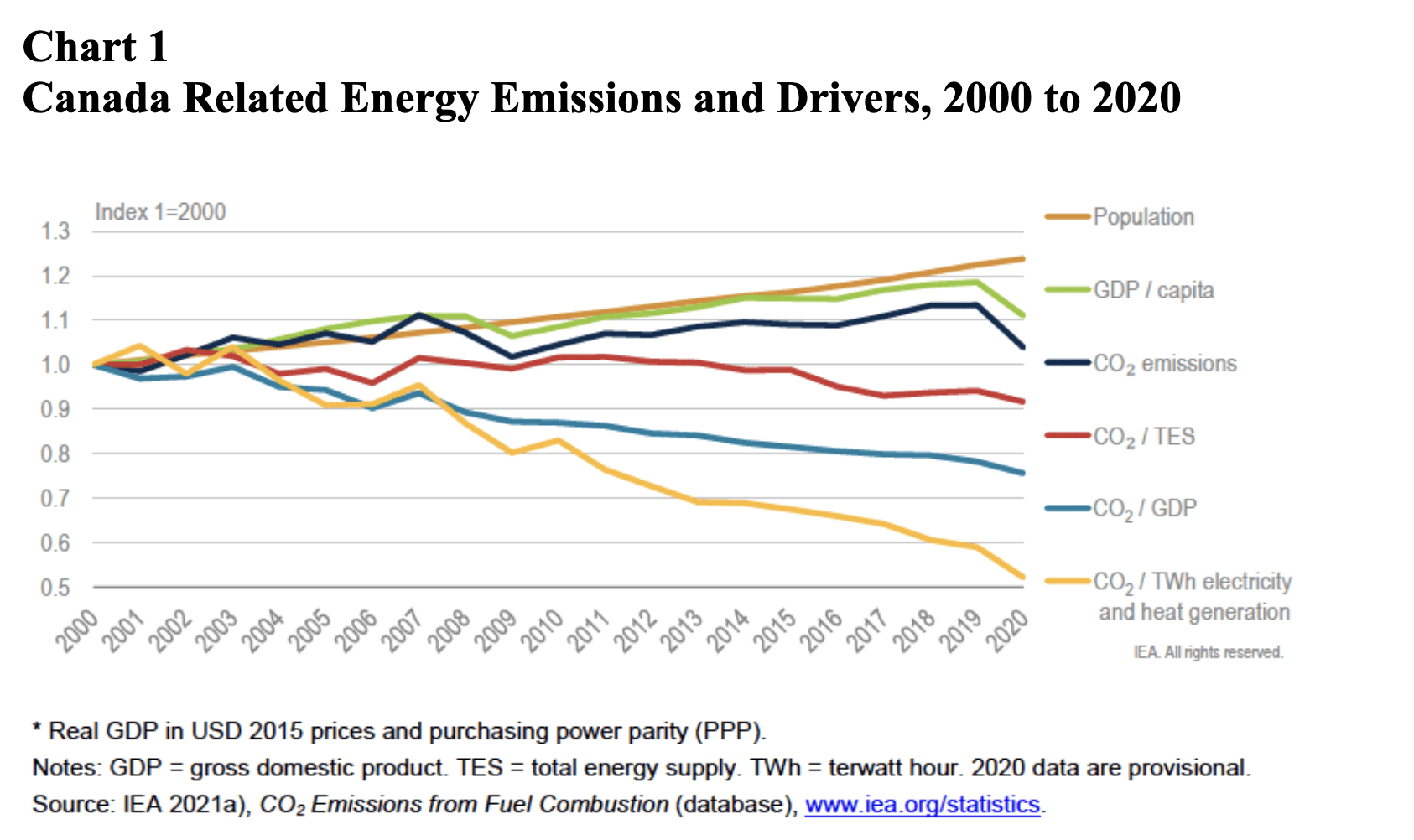

Over the past decade, total energy-related consumption and CO2 emissions grew more than 10 percent, roughly in line with population growth (12 percent). On the other hand, GDP grew about 24 percent (on a pre-COVID basis). This demonstrates a legitimate start to the actual decoupling of economic growth and energy demand. Furthermore, according to the IEA, the carbon intensity of the Canadian economy and energy supply declined by more than 10 percent.

Canada, like many other advanced economies, is on a downward trend with respect to energy intensity. The challenge is that we are starting from relatively high levels of energy intensity.

A highly skilled energy labour force and a proven technology track record are strong assets to drive continued progress in transition. The workforce in the Alberta oilpatch or in the nuclear industry of Ontario, as examples, are more than capable of being trained in green energy technologies. The advances in carbon capture and storage technology as well the commercialization of smaller modular reactors in Canada have established the fact that Canada can compete in this transition.

A series of recent reports by international and domestic energy experts are making some common recommendations on energy transition. The reports include the IEA 2022 Canada Energy Policy Review; 2021 Net-Zero Advisory Body Report (Advice for Canada’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan) and the 2018 Generation Energy Council Report.

There are three overarching recommendations that build on the policy and fiscal supports advanced by federal, provincial, and territorial governments in recent years.

- One, develop an energy transition strategy and plan. Model net-zero pathways by sectors (e.g., oil and gas, transport, buildings, etc.). More energy efficiency (less waste; set targets by sectors); more clean electricity, more renewable fuels; and cleaner oil and gas. Lead by example at the federal level(procurement, investment and management rules). Canada’s commitment to undertake an infrastructure needs assessment is an essential component to the development of a strategy and plan.

- Two, strengthen governance. Invest in data. Enhance consultations and reporting. Better integrate policy and regulatory systems. Strengthen inter-provincial connectivity. Build and strengthen independent analysis and advice — ensure Net-Zero Advisory Body is well supported. Empower Indigenous peoples through greater involvement in regulatory processes on energy projects.

- Three, stimulate strategic investment. Increase federal funding in support of R&D and innovation in clean energy technologies to achieve 2030 and 2050 targets. Get the codes and standards in place (e.g., energy labels, building codes).

As the global economy continues to struggle with instability resulting from geo-political conflict, high energy prices and rising interest rates and inflation, we need governments across Canada to keep the focus on longer term energy transition.

Umer Farooq is a Masters Candidate at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He has a Doctorate in Engineering.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a contributing writer for Policy Magazine.