The Social Costs of Social Distancing

Kevin Page

The word gratitude comes from the Latin word gratia, which infers grace, graciousness and gratitude. Medical journals and popular magazines highlight research that links gratitude to better mental health, better relationships and a reduction in anxiety. In these atypical times of a global pandemic, I feel more gratitude and more anxiety.

I grew up in a working-class family in northwestern Ontario. As with many Indigenous families, much of the food we ate came from hunting, fishing, berry picking and the garden. My mother insisted that we say grace before meals because that “bountiful goodness” came from mother nature. She would have agreed with G.K Chesterton, who said: “When it comes to life, the critical thing is whether you take things for granted or take them with gratitude”. To my Mom, gratitude and kindness were the best path to a life of peace and happiness.

Mother Nature threw humankind and our economy a nasty curve ball in the form of a pneumonia-like disease named SARS-CoV-2 (or COVID-19). How does one express gratitude in 2021 after some 3.8 million deaths worldwide are attributed to the virus, including 26,000 deaths in Canada?

I think gratitude comes from an unprecedented and ongoing global policy response. Millions of lives and livelihoods have been saved.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), more than $16 trillion (US) has been allocated by governments to address the fall-out on the global economy (estimated to be about ($93 trillion US in 2021). Governments and the private sector collaborated to develop and distribute vaccines. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 2.1 billion vaccines have been administered. Global leaders are meeting to ensure we close the vaccination gap, particularly in less developed economies. This was top of mind at the G7 Summit in the UK in mid-June.

I have always felt that I won a lottery in life to be born in Canada. This feeling was instilled by grandparents who fled Poland and Ukraine during periods of great hardship (my surname was changed from Paicz).

Over the past year and half, I have watched our political leaders and public servants in Canada work tirelessly to save lives. Parliaments passed emergency measures to facilitate the shutting down of much of the economy to slow the spread of the unknown virus. The measures came in the form of direct fiscal supports (e.g., the wage subsidy or emergency response benefit), as well as tax deferrals and liquidity measures totaling more than C$600 billion in our $2.3 trillion economy (nominal GDP).

Over the past year and half, I have watched our political leaders and public servants in Canada work tirelessly to save lives. Parliaments passed emergency measures to facilitate the shutting down of much of the economy to slow the spread of the unknown virus. The measures came in the form of direct fiscal supports (e.g., the wage subsidy or emergency response benefit), as well as tax deferrals and liquidity measures totaling more than C$600 billion in our $2.3 trillion economy (nominal GDP).

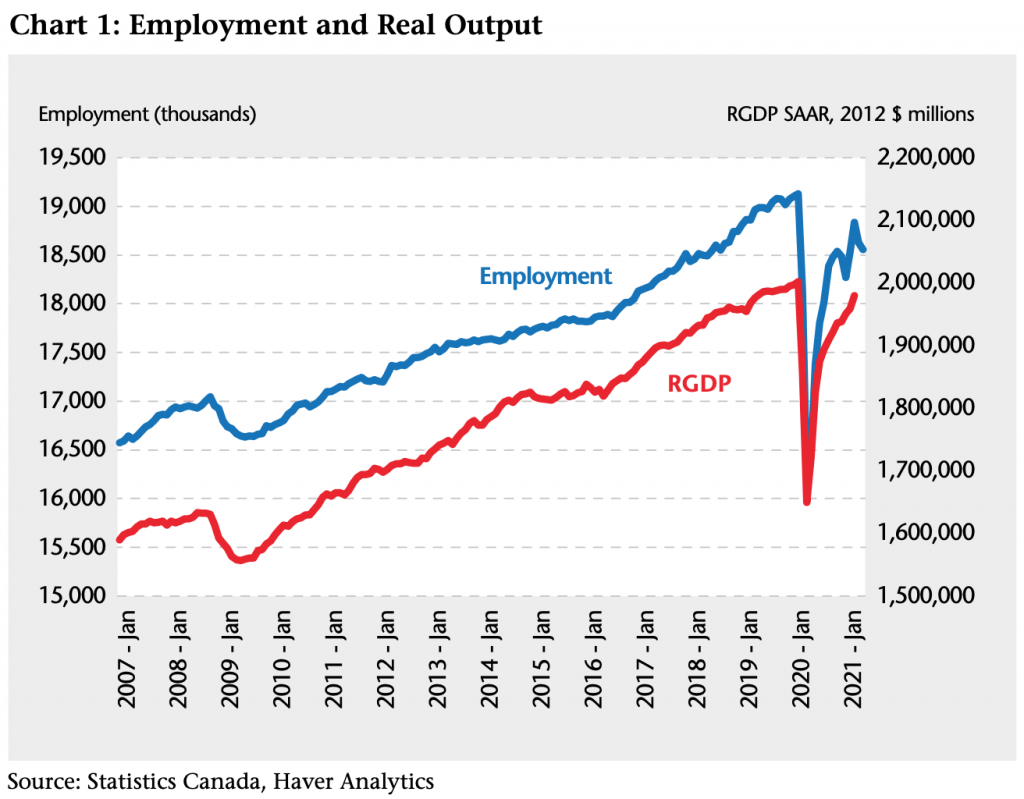

Notwithstanding the incredible Canadian fiscal supports, the negative impact of the social distancing measures on the Canadian economy was unprecedented in our lifetime. From Chart 1, you can see the declines in real output and employment during the 2020-21 pandemic recession far outweigh the relative declines in the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

The 2020-21 global pandemic recession will have a placeholder in economic history books. Economists Eduardo Levy Yeyati and Federico Filippini estimate the total economic and social costs of the pandemic could be close to 100 percent of global GDP. You get a big number when you work through the various components of loss—long term GDP; fiscal supports; the loss of life and the human capital loss related to shutting down the economy for an extended period of time.

In the midst of a deadly contagion, governments had little choice but to implement social restrictions to contain it. Mindful that many governments and public health agencies were caught unprepared with respect to personal protective equipment, we need to better understand the costs and benefits of social distancing.

Basic models look at benefits of social distancing through the lens of the total value of lives saved. The costs are expressed simply as lost GDP. A recent study (Thunstrom, Newbold, Finnoff, Ashworth, Shogren) published online by Cambridge University Press suggest the net benefits of social distancing can be significant.

One of the key unknowns in the current cost-benefit studies is the potential for economic scarring. Significant recessions, such as the one catalyzed by the 2008 global financial crisis, have long-term impacts on business and human capital. It can take many years for output and employment to get back to their trend lines (see Chart 1). Losses may never be recouped.

As the Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has said: “COVID-19 is not an equal opportunity virus, and the economic impact has not been an equal opportunity impact.”

Saving lives with social distancing is complex. There are terrible human trade-offs. Not all lives are the same. We are different. There are people whose lives are vulnerable to a coronavirus (e.g., seniors, people with pre-existing respiratory and immune issues) and there are those whose lives who are more vulnerable to mental health problems; substance abuse and domestic violence that can be negatively impacted by social distancing.

I think we have all seen (up close) the negative human impacts of social distancing. My anxiety goes up when I see people struggling with fear of infection or loneliness exacerbated by social restrictions. In Canada, more than 4 million people live alone. The percentage of solo dwellers aged 15 and over living in private households is about 14 percent, and has been rising over the past few decades.

The New York Times writer David Brooks has made the case that we must be prepared to take off our pre-covid masks once we get through the COVID pandemic. We will need to work on our collective mental health by building meaningful relationships with others. Relationships over ZOOM are not the same as the face-to-face relationships we get by gathering for social and work activities.

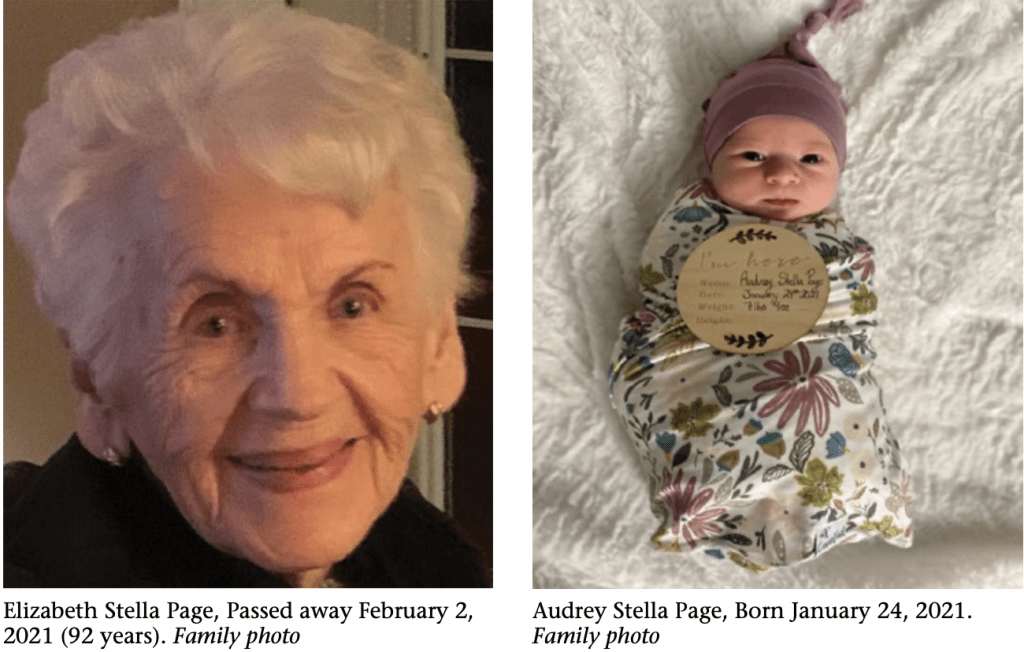

My mom passed away in February. About a week prior to her passing I became a grandfather. My mom’s last words to me were words of gratitude and the joy of another great-grandchild. I will try not to forget the lesson of gratitude.

My mom passed away in February. About a week prior to her passing I became a grandfather. My mom’s last words to me were words of gratitude and the joy of another great-grandchild. I will try not to forget the lesson of gratitude.

Contributing Writer Kevin Page is President and CEO of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Democracy at University of Ottawa. He was previously Canada’s first Parliamentary Budget Officer. A native of Thunder Bay, he lives in Ottawa with his family.