The Three Amigos: Getting North America in Gear Again

PA

Colin Robertson

November 14, 2021

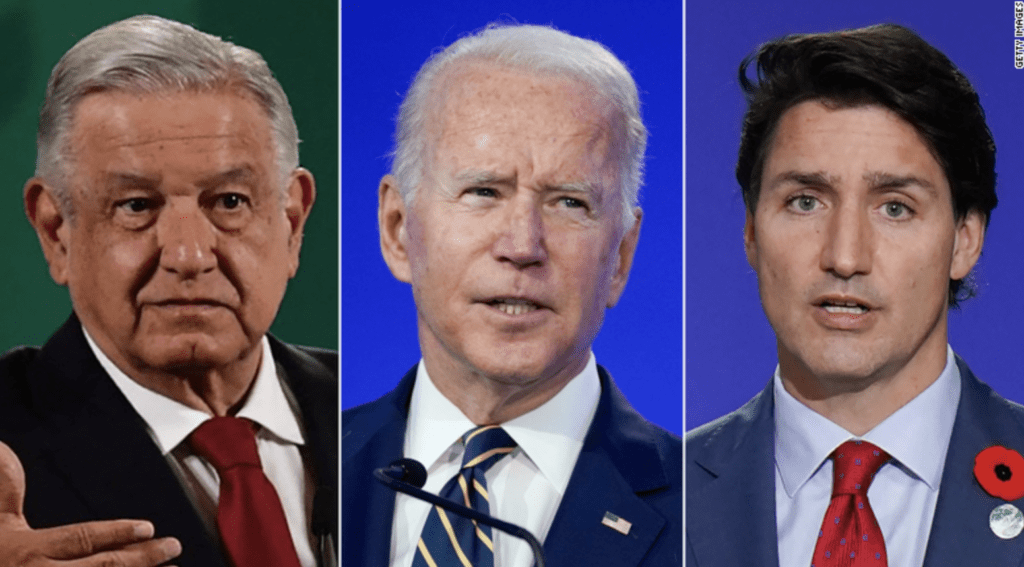

The North American idea gets a revival this Thursday in Washington when President Joe Biden hosts Canada’s Justin Trudeau and Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador for the first “Three Amigos” summit in five years. According to the White House, their meeting “will reaffirm their strong ties and integration while also charting a new path for collaboration on ending the Covid-19 pandemic and advancing health security; competitiveness and equitable growth, to include climate change; and a regional vision for migration.”

The economics of continental collaboration are already proven; what is lacking is not the vision for a continental community, nor the business commitment, but the political will.

NAFTA launched two decades of successful trade integration, creating jobs and prosperity in all three nations. In recent years, various US studies — the Council on Foreign Relations, Harvard’s Belfer Center, the George W. Bush PresidentialCenter, the Wilson Center – demonstrate that with resources, technology, a growing market, and a young educated work force, closer North America collaboration will create even more jobs and prosperity.

Business has long bought into the advantages of continental trade, investment and integrated supply chains. The North American Strategy for Competitiveness (NASCO) has worked since 1994 to give it practical effect. The recent CP-Kansas CitySouthern deal creating the first single-line rail network linking Canada, the US and Mexico is just the most recent example of our increasingly integrated electrical and fibre-optic grids, roads, rail, ports, and pipelines although we need to do more to harden them against cyber-threats including ransomware.

In Washington this week, there will be well-meaning pledges by this newest iteration of the Three Amigos on climate and COVID. There will be commitments to joint economic recovery that is sustainable, inclusive and that will grow the middle class. They will nod vigorously that the five-year hiatus in these neighbourhood get-togethers was far too long and that they must do this again.

But bromides aside, can the trio, in their own fashion each a progressive, tackle the tough issues like migration, border management and protectionism? Will the dollars being poured into the various national “Build Back Better” projects be coordinated in a trilateral industrial policy? Could we collaborate in a Marshall Plan-like effort to mitigate the effects of climate, crime and corruption in Central America that daily sends hundreds fleeing north through Mexico with the hope of sanctuary in the US? Probably not, but perhaps they can at least begin a process for future action.

While it won’t be acknowledged, much of the serious discussion, certainly the serious negotiations, will be devoted to the “dueling bilaterals” between Mexico and the US, and then Canada and the US.

Can the trio, in their own fashion each a progressive, tackle the tough issues like migration, border management and protectionism? Will the dollars being poured into the various national ‘Build Back Better’ projects be coordinated in a trilateral industrial policy?

Biden will inevitably devote more time to the Mexican issues because they are demographically vital and politically sensitive. The Latino population in the US is more than 62 million, with most claiming Mexican roots, and their votes count.

The American fear, mostly false, that Mexico sucks up American manufacturing jobs, goes back to the original NAFTA. The pundits gave Al Gore the win in his 1993 debate with Ross Perot but many Americans in the Rust Belt did not, and Perot’s comment about “the giant sucking sound” of jobs moving to Mexico resonated. For them, Donald Trump’s “America First” later made sense. So does Biden’s promise of “Made in America” and “Buy America”.

Trudeau will pick up with Biden where our new foreign minister, Mélanie Joly, left off during her meeting last week with Secretary of State Tony Blinken. They discussed the geo-strategic issues – climate, COVID, China, the upcoming democracy summit, Afghanistan, Haiti – as well as the Enbridge pipelines 5 and 3 and the protectionist measures in the administration’s “Build Back Better” and infrastructure legislation.

The Joly-Blinken meeting was important on several counts: it affirmed that she will be the lead minister on US relations (it had gotten confused when Chrystia Freeland retained oversight after leaving Foreign Affairs). It also delegated discussion of the ‘irritants’ to the ministerial level (and with the impending arrival of US Ambassador David Cohen, the quiet diplomacy of our two ambassadors can resume). There has been an unfortunate tendency to want to push every problem to the prime minister’s discussions with the president. It baffles the Americans, who think that when G7 leaders meet the president, the top table should not be dealing with what Condi Rice called the ‘condominium issues’.

The dueling bilaterals reflect the natural order of our relative asymmetries in trade.

For both Canada and Mexico, the US is the preponderant trading partner, with 75 percent of Canadian exports going south and close to 80 percent of Mexican exports headed north. By contrast, while we shift positions as America’s first or second largest export market, Canada and Mexico each only take around 18 percent of American exports. We both like to point out, however, that our trade and investment generates around nine million American jobs apiece.

The Canada-Mexico trade relationship blossomed under NAFTA and today Mexico is our third-largest trading partner but again it is asymmetrical: Canada’s $28 billion in direct investment (mining, energy, banking) in Mexico eclipses Mexico’s $2 billionin Canada, and Canada imports $30 billion in goods from Mexico while we only sell $6 billion. Ours may be an inevitable alliance, given our shared neighbour, but while Canadians flock to Mexico for sun, sand and tequila, it has never jelled. Both sides need to do more. A good start would be more student exchanges.

For the US and Mexico, the continuing conversation is always about their 1,954km border and the discussions are always difficult. For many Americans, their southern border is about what they see on their screens: pictures of contraband and the huddled masses striving to get in. Many Americans still support Trump’s wall.

Even though their Canadian border is over four times longer (8891 km), the daily crossings of roughly 400,000 people are mostly without controversy now that the border has reopenedafter the 18-month COVID containment. Canadian governments have always been careful to underline the border differentiation to the Americans and avoid common cause with Mexico. While it caused temporary resentment with Mexico, we turned down a joint approach after 9/11 and then negotiated our “Smart Border”Accord. It was the right course then and it continues to be the right course, especially if we ever move to shared facilities.

There has always been the recognition that while a trilateral approach is preferred, the partners can move at different speeds.

We took the same approach with the Beyond the Border and Regulatory Cooperation initiatives launched by Prime Minister Stephen Harper and President Barack Obama. With focus on relieving the ‘tyranny of small differences’ it has since been institutionalized into the Canadian and American bureaucracies. With the Trudeau-Biden Roadmap announced during their February virtual summit, we have a comprehensive plan of action with its focus on climate, COVID and building back better, advancing diversity and inclusion, bolstering security, including NORAD renewal, and building global alliances.

The idea of closer North American integration took off in the 1980s under conservatives Ronald Reagan, Brian Mulroney and Carlos Salinas. President Reagan envisioned the day “when the free flow of trade, from the tip of Tierra del Fuego to the Arctic Circle, unites the people of the Western Hemisphere in a bond of mutually beneficial exchange, when all borders become what the US-Canadian border so long has been: a meeting place rather than a dividing line.” Reagan’s words are an ironic reminder of just how far the current Republican party has travelled in the opposite direction.

The crowning achievement of Reagan/Bush 41, Salinas and Mulroney would be the NAFTA that endured despite changes of party and leaders in the United States and Canada. To their credit, Bill Clinton and Jean Chrétien endorsed the new continental arrangement. Growing trade and investment among all three partners helped ensure its endurance, despite Donald Trump, who repeatedly threatened to tear up the “worst trade deal ever”.

The new NAFTA – CUSMA to Canadians, USMCA to Americans and TMEC for Mexicans — is more about managed trade than free trade, especially in cars and trucks, our most traded manufactured commodity. But it also incorporates some of the best features of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), including digital trade, transparency, environment and labour. Ironically, Trump cavalierly repudiated the TPP as one of his first executive orders. Rebranded, at Canadian insistence, as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) it is considered the gold standard for trade pacts in the Asia-Pacific with China, Taiwan and the United Kingdom knocking at its door.

The Biden administration embraced the new NAFTA because to secure its passage in Congress the Trump administration was obliged to stiffen its provisions on labour and the environment. The Biden team has now launched their first dispute panel to enforce what they see as Canadian wriggling out of its dairy obligations. Meanwhile, we continue to seek redress on softwood lumber.

We must find ways that respond to the needs of the administration, especially on China and continental security, while actively reminding Congress that jobs in their districts depend on trade and investment with Canada.

It’s not that Joe Biden doesn’t like Justin Trudeau, whom he once described as a champion of liberal internationalism. Biden sees Canada as a friend and ally, words repeated last week by Secretary Blinken on meeting Joly. In the new geopolitical contest of authoritarianism encroaching on democracies, the Americans see us as kindred spirits. But when it comes to trade, Biden leads a party that has a deep ideological belief in protectionism as the only way to defend American jobs.

For Canada, this means practising patient, astute diplomacy. We must find ways that respond to the needs of the administration, especially on China and continental security, while actively reminding Congress that jobs in their districts depend on trade and investment with Canada.

Biden’s “Made in America” e-vehicle tax credit would mean we could not sell to the US the electric vehicles that Ford will produce in Oakville and batteries that Stellantis will make in Windsor. The North American automotive industry is deeply integrated and competing as a bloc in the manufacture of a world-class e-vehicle and battery industry makes good economic sense for all three countries. Many of the critical minerals vital to the new sustainable economy are mined in Canada. This should give us some leverage. But are we using it?

The late scholar Bob Pastor, who served in the Carter administration, made the case for the North American Idea. He envisioned a “community” not a “union”. As the late George Shultz argued, it respected national sovereignties and celebrated the federal nature of the three democracies. Their provinces and states would be the incubators of ideas and innovation. North America would avoid the top-heavy bureaucracy of the European Union. But a pooling of talent, resources and investment would create a powerful and competitive bloc that would benefit all its citizens.

This is the idea that inspired the first North American Leaders’ summit – hosted by George W. Bush at Waco in 2005 with Canada’s Paul Martin and Mexico’s Vincente Fox. They launched the Security and Prosperity Partnership. It suffered from too much ambition and too little realization of its many objectives and by 2009 it had succumbed. Justin Trudeau, Barack Obama and Enrique Pena Nieto created a North American Climate, Clean Energy and Environment Partnership. Its rejuvenation should be one of this week’s objectives.

The North American idea still makes sense. This week’s trilateral signals that the spirit taking us forward is once again in gear.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former Canadian diplomat who served in senior postings in Washington, New York and Los Angeles, is Vice President and Fellow of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.