The Waiting

By Douglas Porter

December 8, 2023

Patience is not just a virtue, it’s a necessity when it comes to the current outlook for central banks. That’s because, even as markets have talked themselves into believing that rate cuts are practically imminent, the policy turn is likely further down the road than most anticipate. Why? This is a cycle like none other in the past 40 years—the starting point for underlying inflation is well outside the comfort zone, and most economies remain surprisingly resilient in the face of stiff headwinds. Seemingly since the moment that rate hikes began last year, markets have consistently underestimated how far rates would rise and overestimated how quickly they would come back down. Little has changed. Simply: objects in the front view are further away than they appear.

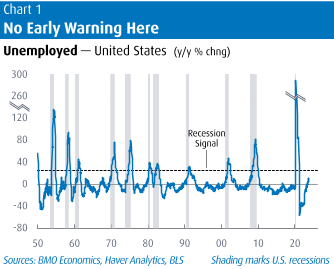

That point was loudly echoed by Friday’s U.S. jobs report, which was consistently sturdy. Not only did headline jobs top expectations with a 199,000 advance for November, but hours worked were solid (+0.3%), earnings perked up 0.4%, and the jobless rate peeled back two ticks to 3.7%. The latter was driven by a 747,000 snapback in household employment, leaving it up 2.1% y/y (versus 1.8% for payrolls). Let’s just say that 2% job growth is in a different hemisphere from recession. In a similar vein, the number of Americans counted as unemployed is now up less than 5% from a year ago. A tweak to the Sahm Rule suggests that it takes about a 25% y/y rise in the number of unemployed people to signal a recession (Chart 1 shows that has a perfect track record in the post-war era). So, again, the U.S. economy is a long way from serious difficulty.

Reinforcing that message was ongoing stability in initial jobless claims, a solid ISM services print for November (52.7), and even a bounce in consumer sentiment in December (University of Michigan). In the wake of this dash of reality, markets stepped back a bit from the most aggressive rate cut expectations. Still, the odds of a cut are pegged at nearly 50% as soon as March, and a plurality of economists look for cuts to commence by Q2 of next year. Of course, these views could shift following next Wednesday’s FOMC meeting or even Tuesday’s CPI, although most have largely tuned out Chair Powell’s hawkish remarks. Since peaking around mid-October, two-year yields have dropped roughly 50 bps to about 4.7%, and 10s have plunged 75 bps to just above 4.2%, even with some back-up late in the week.

It’s certainly not just the Fed that is expected to soon start cutting. The consensus is convinced that the ECB is finished, and that it may send such a signal at its meeting next week. This has only been reinforced by the fact that headline Euro Area inflation has calmed to just 2.4% in November and real GDP has seen precisely no growth in the past four quarters. While underlying inflation remains sticky at 3.6% in the region, many expect core to crack as well with growth stalling and inflation expectations perhaps further undercut by the latest slide in oil prices. Even with a partial late-week recovery, crude still fell about 5% this week to a five-month low of just over $70.

Markets are also looking for rate cuts in Canada by the spring. In fact, the Bank of Canada is widely expected to be a step or two ahead of the Fed on the way down Mount Lofty Rates, reflecting the much higher interest sensitivity of the household sector. Yet, by all appearances, the BoC is not on board. This week’s rate announcement was mostly as expected, with the third hold at 5% accompanied with a mildly rote hawkish message. Even as the Bank continues to warn that further rate hikes may be necessary, the entire conversation outside of Ottawa has turned to when, and by how much, rates will be cut. To use a football analogy, it’s a bit like Team A is still deciding whether to punt or go for it on fourth down (well, third down in Canada), but Team B’s offence has already run onto the field.

For example, even before the Bank has stopped talking about rate hikes, the two-year GoC yield has cascaded down by more than 80 bps in the past two months. In turn, this has sliced the all-important 5-year yield, which influences mortgage rates, by more than 90 bps to below 3.5%. That leaves these yields roughly unchanged since the start of 2023, and 30-year yields are now actually down a tad over the same period. In other words, the great bond sell-off over the summer and early fall has now been almost entirely reversed in Canada, as markets have rapidly shifted from “higher for longer-er” to “rate cut fever”.

The issue in the scenario above for Team B (markets) is that Team A (BoC) still has possession. We’ll hear again from Team A’s captain (Governor Macklem) in a speech next Friday, but it would be surprising if he deviated from the hawkish pushback by the Bank. The conventional wisdom is that the Canadian economy is succumbing to rate hikes and inflation is poised to melt further, paving the way for rate cuts early next year. And, yet, auto sales continue to rebound forcefully amid more plentiful supplies, home sales appear to have stabilized (albeit at low levels), and job gains are still chugging along. More troubling for the BoC on the inflation outlook is that unit labour costs have spiked more than 6% y/y—a 30-year high—driven by solid wage growth and declining productivity. The bottom line is that the wait for rate relief may be longer than markets currently expect.

For this week’s theme, we’ve liberally adapted that keen economic observer, Dr. Seuss:

The Waiting Place

Waiting for a train to go or a ship to come, (supply chains)

or jobs to slow or stocks to run,

or core to lose mo or the bell to ring,

or the Fed to pivot or waiting around for a Yes or No

or waiting for their hair to grow. (more applicable for some than others)

Everyone is just waiting.

Waiting for rate hikes to bite

or waiting for wages to take less flight

or waiting around for Friday night (no edit required here)

or waiting, perhaps, for their Uncle Jay

or a dip in oil, to show a Better Way

or a string of pearls, or pundit rants

or a curve that curls, or Another Chance (to get long) .

Everyone is just waiting.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.