The (Warning) Shot Heard Round the World

Douglas Porter

November 10, 2023

Following last week’s furious rally in almost everything, markets took a step back in sombre reflection this week. Egged on by cautionary words from central bank heads, yields moved back up, stocks simmered down, and the U.S. dollar popped firmly back into the plus column. Fed Chair Powell unsurprisingly carried the most sway, issuing a blunt warning in comments at the IMF that they were “not confident” that rates had been hiked enough yet to fully corral inflation. He also opined that a few months of encouraging inflation data had given the Fed “a few head fakes”, so it didn’t want to back off too soon. Combined with a sour 30-year Treasury auction, yields dutifully rose from mid-week lows, with the two-year note touching the 5% threshold again.

The Bank of Canada added to the more hawkish hue, with a two-pronged effort. In what had shaped up to be a relatively quiet week for Canadian economic data and events, the Bank’s comments landed with a splash. First, the deliberations from the late-October meeting were much more eventful than earlier versions (although admittedly this was only the seventh instalment, having just begun the practice at the start of 2023). The true eye-opener here was that we apparently have a real, live split within the Governing Council on the appropriate direction for policy. Even amid the no-drama decision to keep rates steady, “some members felt that it was more likely than not that the policy rate would need to increase further to return inflation to target”. On the surface, that may seem pretty innocuous, but this is the first hint ever that there may be some—gasp!—disagreement among BoC policymakers.

Reinforcing the mildly hawkish message, Senior Deputy Governor Rogers intoned in a Thursday speech that, “there are reasons to think they may not” come back “to the low rates that we all got used to”. She also warned about the steep buildup in government debt in recent years, possibly keeping a flame under inflation. This was on top of a sharp comment in the deliberations on government spending and how it threatened to keep the upward pressure on rates. True, the BoC does not want to veer out of its lane and sway fiscal policy, but there is certainly some backseat-driving going on here. In fairness, there is now a busload of backseat drivers on the monetary policy front, with politicians of all stripes feeling zero compunction about weighing in.

It wasn’t just words from central bankers this week. The Reserve Bank of Australia weighed in with action, hiking its policy rate 25 bps to 4.35%—less than a week after many (ahem!) had declared a global pause in the rate-hike campaign. The RBA looks to be the exception that proves the rule—it was late to the tightening game, its cash rate is well below most others, yet inflation is on the meaty end of the spectrum at 5.6%.

How to assess the sudden hawkish campaign? Some of this could simply be posturing, especially in light of the massive rally in both stocks and bonds last week. After nodding in approval at the earlier tightening in financial conditions, it’s no surprise that officials are now wagging their collective finger at any signs of exuberance in markets. But policymakers are also legitimately concerned that inflation is still smoldering, and it would only take a spark to reignite it into a full blaze. A spate of relatively generous wage deals, including the UAW and the actors’ guild, suggest that underlying pressures from the inflation spike have a long tail. In Canada, the average first-year adjustment in Q3 wage settlements was 6.4%, the highest since 1991 and up from 1.9% a year ago.

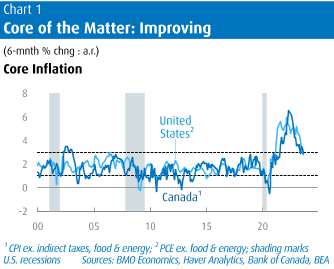

Yet, despite these misgivings, we will point to some more encouraging news on the inflation front. And, recall, this comes from an avowed inflation hawk. While Powell warned about a few months of head fakes, note that the six-month trend in the U.S. core PCE deflator—which, after all, is the Fed’s main inflation metric—has cooled to a reasonable 2.8% annualized pace (Chart 1). This is the slowest six-month trend since early 2021, when central bankers were still actually welcoming a bit of inflation. Given some meaty monthly increases late last year, it’s entirely possible that the 12-month trend on the Fed’s preferred core measure could also grip a 2-handle by early 2024 (from 3.7% now). The key point is that underlying trends are mild enough to stay the Fed’s hand.

We won’t have to wait long for some confirmation that inflation is steadily calming, with the U.S. CPI the main course on next week’s calendar. Headline inflation will be greased lower by a sharp pullback in gasoline prices, which should hold the monthly CPI rise to a mere +0.1% which, in turn, should clip the annual rate to a manageable 3.3%. However, core CPI will look much stickier, with a 0.3% m/m rise expected to keep the annual pace steady at just above 4%.

It’s a broadly similar story for Canadian inflation, despite the clear separation between the two economies on the growth front in recent quarters. And, ultimately, it’s this lack of daylight between U.S. and Canadian inflation that helps explain why we don’t anticipate much monetary policy divergence in the year ahead (a topic we explore in depth in this week’s Focus Feature). Canada’s October CPI—due November 21, the same date Ottawa has chosen to release its Fall Economic Statement, as it were—is expected to see a gasoline-driven dive in headline inflation to the low 3s.

The many measures of Canadian core CPI are generally firmer and still out of the comfort zone of 1%-to-3%. However, the BoC’s one-time crush, CPIX, has dipped to 2.8% y/y (it helpfully removes mortgage interest costs, among other volatile items). Looking at a measure more comparable to international norms, the simpler CPI excluding food, energy and indirect taxes (which would thus take out the hot-button carbon taxes) has eased to 3.2% y/y. Similar to the U.S. core PCE deflator, it too has dipped below a 3% clip in the past six months. Even the annual pace is clearly at the low end of core trends among advanced economies, as Euro Area core CPI was 4.2% last month and the U.K. is still hanging around 6%.

Summing up, we find ourselves in the odd position of being a bit more optimistic than the central banks that inflation is finally on the right path lower. That’s a place we haven’t been in nearly three years. This week’s pullback in oil prices to well below $80, or less than the 12-month running average, adds another positive note. Having said that, we recognize that their collective caution on the inflation outlook is well earned by the experience of the past few years. And, as much as markets are now anticipating a turn to lower interest rates, we do suspect the surprise in the year ahead is just how patient the central banks prove to be on the trip down.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.