This is the End, Beautiful Fed, the End

Douglas Porter

April 21, 2023

The Federal Reserve is widely, albeit not universally, expected to hike by one more 25 bp clump next week. And this is widely, albeit not universally, expected to be the last such hike following a string of ferocious rate increases over the past 14 months. Assuming that we and the consensus are correct, the May 3rd move will take the fed funds rate to a range of 5.00%-to-5.25%, a full and tidy 500 bps above where the tightening cycle began. Curiously, it will also take rates almost precisely back to where they peaked in the 2004-06 cycle (5.25%), which ended in the catastrophic 2008 financial crisis… but, we won’t mention that part.

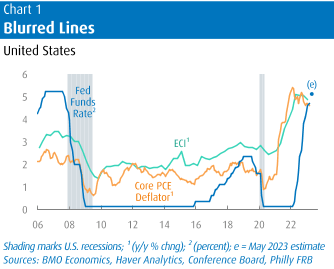

Short-term interest rates of just above 5% will perch them a bit higher than the latest trends in both core inflation and the best measure of wages (Chart 1). The core PCE deflator eased slightly in March to 4.6% y/y, down from last year’s peak of 5.4%, but still a long, long way from the Tipperary of the Fed’s 2% target. Similarly, the employment cost index eased somewhat in Q1 to a 4.8% y/y pace (from 5.1% in Q4), although short-term trends are not relenting and the wage component is still up 5.0% y/y. Our contention for much of the past year is that short-term interest rates would need to at least rise above underlying inflation trends to truly break underlying inflation trends. And while core inflation looks sticky, it is now mission accomplished on the degree of rate rises.

The economy also weighed in with some pretty compelling arguments for the Fed to now move to the sidelines. Real GDP cooled to a surprisingly mild 1.1% annual rate in Q1, and early indications point to a slower Q2. Regional manufacturing surveys are quite soft for April, and the consumer’s momentum stalled heading into the month. We are maintaining our view that overall GDP will take a small step back this quarter and next. Meantime, the regional banking sector stress flared again this week, mostly countered by solid tech earnings. And, the debt ceiling dance is picking up the pace, and is now expected to reach its crescendo in July.

Financial markets absorbed the likelihood that the tightening cycle is indeed drawing to a close with another back and forth week. The S&P 500 is poised to finish the month with a small gain but is now almost exactly back to where it stood a year ago (it finished April 2022 at 4,132). Bond yields also bobbed and weaved on this week’s mixed events, but mostly weaved lower to below 3.5% for the 10-year Treasury. For reference, that’s also not so different from where we stood a year ago, as 10s first pushed above the 3% threshold around this time in 2022. The latest dip in yields also got a small subtle push from cooled oil prices, as WTI slid to $75 after punching above $83 just two weeks ago on OPEC+’s production cuts.

The debate now turns to how long before the rate cuts can commence. Of course, we need to be certain this rather dramatic tightening is truly over before drawing any strong conclusions. And recall that just days before the banking crisis broke open, Chair Powell was starkly warning that rates needed to rise much further than the Fed had previously warned. Only the most hawkish are still suggesting that’s still the case, and the rolling stress in regional banks and the upcoming debt ceiling fight are likely to put any further rate hikes on ice. While the Fed is probably not going to send an explicit pause message at the May meeting, that will likely be the body language in the press conference.

Assuming next week is the end, history suggests that rates could begin to come down around the turn of the year. The first rate cut is normally about 6 to 8 months after the last hike, which would take us to around the mid-December FOMC meeting. However, there is nothing “normal” about this cycle, and no one should expect a textbook Fed response on the downside for rates. Perhaps the most glaring difference this cycle compared to other recent episodes is how far core inflation remains from target, pointing to the risk of higher for longer. The counter case is how far rates have risen and the raft of challenges facing the economy, pointing to the risk of a sooner policy shift. We believe these factors are largely offsetting and continue to look for rate cuts to commence in early 2024.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.