Toward a New Canada-US Model in Forestry Trade

Eric Miller

In international relations, some things seem eternal. One of these is lumber trade frictions between Canada and the United States. The two countries are on the fifth round of the softwood lumber wars in the modern era, but the roots of the conflict run much deeper. These disputes continued through the negotiation of the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement, North American Free Trade Agreement, World Trade Organization agreements, and Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement. Despite all of this “free trade”, Canadian softwood lumber stubbornly remains “managed” in trade with the United States.

Some commentators deride the forestry sector as being antiquated. Canadian schoolchildren are taught the phrase “hewers of wood and drawers of water”, which comes from the Bible but was popularized by Harold Innis as a shorthand for the resource dependency of Canada’s economy.

Yet, far from being an industry of the past, forestry is central to North America’s ability to meet the greatest economic challenge of the next two decades – the transition to a low carbon economy. In this context, trees are increasingly seen as carbon sequestration machines.

One of the challenges for the coming decades is to introduce into our trade discourse the idea of free trade in environmental goods, of which forest products are a central example. Trade is a powerful vehicle for efficiently allocating goods. To do this, Canada and the United States need to move away from the practice of viewing Canadian forest products as a mere commodity to be restricted.

If one were to boil down the why Canada and the United States have had a centuries old dispute over forest products, it comes down to three interrelated facts. First, the United States produces, on average only two-thirds to three-quarters of the lumber it consumes. Second, Canada has a larger volume of accessible forest lands than the United States, making the Americans fear competition from Canada. Third, tariffs keep US lumber prices higher than they otherwise would be, driving lumber company profits.

The lumber dispute dates to the very founding of the United States. The first important law passed by the first Congress in 1789 established a US tariff schedule, including a 5 percent duty on most forest products. Given geographic proximity, the future provinces of Canada were the primary sources of imports. By the 1830s, the duty on sawed lumber reached 25 percent.

From 1854-1866, the Reciprocity Treaty provided duty-free, quota-free access to all goods, including forest products. In the 1853 congressional debate, Ohio Congressman N.S. Townshend offered a surprisingly contemporary analysis:

“The British Provinces have almost inexhaustible supplies of pine timber. This is greatly needed…But Maine, for which… the best timber is already cut, wants to exclude lumber (from) the Canadas, and to force her spruce and inferior pine on the market at high prices. It is asserted that unless competition… is prevented…, her…lumbermen cannot make fair wages… (Yet)…protection is not designed for their benefit but for the benefit of the wealthy few.”

When the US abrogated the treaty in 1866, Canadian forest products faced a 20 percent duty.

In the 20th century, Canadian lumber enjoyed tariff-free access (1913-1930), was subject to a high tariff (1930-1935), and faced a tariff-rate quota (1935-39). In the post-war period, demand for Canadian lumber was high as the US economy boomed. Renewed petitions for protection came in the 1960s. By the 1980s, the stage was set for “Lumber I”.

In the post-war period, the broad thrust of US trade policy was to lower tariffs. Impacted industries were no longer able to directly petition Congress for relief, so they increasingly turned to trade remedy processes.

Lumber I began in October 1982 when the US industry sought an investigation into Canadian subsidies. Ultimately, the Department of Commerce found that the Canadian stumpage regime was not countervailable. Yet, the US. industry was unwilling to accept this outcome. In 1985, five companies came together to form the “Coalition for Fair Lumber Imports” (now the US Lumber Coalition.) In May 1986, the Coalition asked Commerce to again investigate Canadian softwood, thus launching “Lumber II:. This time, Commerce found evidence of subsidies. It levied a 15 percent duty in its preliminary determination. In December 1986, Canada negotiated a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with United States in which it agreed to impose a 15 percent export charge, but allowed provinces to implement in-kind measures, such as increasing stumpage fees and privatizing silviculture management.

The MOU was reached right in the middle of the Canada-US Free Trade (FTA) talks. It allowed the two parties to exclude softwood lumber from the negotiations. Given its history, lumber had the potential to sink the whole agreement. Yet, Canada’s experience in Lumber II directly informed its FTA negotiating strategy. It insisted on the inclusion in the agreement of a mechanism to review and settle disputes related to the application of anti-dumping and countervailing measures.

With this mechanism in hand, Canada withdrew from the MOU in 1991. The US industry immediately petitioned for an investigation, so beginning Lumber III. After a series of determinations and counteractions, Canada appealed the US findings to the FTA binational dispute settlement panel, which eventually led to their reversal.

In 1994, the US implemented the World Trade Organization (WTO) Uruguay Round Agreements. Included in this package were amendments that ensured that Canada could not use the same strategy that succeeded in Lumber III. In April 1996, Canada and the United States agreed to a five-year Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA-1996). It applied a Tariff-Rate Quota to softwood exports from the four biggest provinces in exchange for not initiating a new trade case. Nevertheless, the US launched a case in 1998 over B.C. stumpage and classification issues.

Three days after SLA-1996 expired in 2001, the Coalition filed a countervailing duty petition and its first ever anti-dumping petition. So began Lumber IV. Commerce found in favor of the US industry. Canada turned to both the NAFTA and WTO dispute settlement systems. A NAFTA Panel found that while the Canadian industry was subsidized, the 18 percent tariff ordered by Commerce was too high. The WTO Panel found that provincial stumpage regimes constituted a “financial benefit”, but it was not enough to be considered a subsidy. The US turned to the NAFTA Extraordinary Challenges Panel, but its claims were dismissed.

Shortly after these decisions, Canada and the United States negotiated a new Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA-2006). It locked in managed trade and lumber peace for seven years with the option to renew for an additional two years. Additionally, SLA-2006 included a commitment to refrain from trade action for one year after its expiration. Post-moratorium, the Coalition swiftly petitioned Commerce to start an investigation, so beginning Lumber V.

Lumber V began around the time of the 2016 US election. A leaked document from Donald Trump’s transition team suggested that he wanted to use the NAFTA renegotiation to force permanent limits on Canadian forest products exports to the United States. Despite dreams of a quick win, the CUSMA negotiations dragged on through much of his presidency. Measures to permanently address the Canada-US lumber dispute were left out, just as in NAFTA and the FTA.

What is the key lesson from these decades of disputes? Free trade agreements cannot deliver a long-term resolution to this battle. Canada is compelled to defend itself in every instance where its forestry regime is challenged. There is no prospect for permanent lumber peace between the two countries.

Yet, while the old lumber game rolls on, the importance of wood in building a low carbon economy only grows. A key question for the future is how can trade policy enable the free movement between the United States and Canada of wood that is directly used to off-set higher carbon materials and processes.

In 2014, 46 WTO members, including Canada and the United States, set out to negotiate an Environmental Goods Agreement. The idea was to ensure duty-free, quota-free trade in goods that directly contributed to building a cleaner, healthier environment.

While multilateral free trade in environmental goods has not succeeded, negotiating a meaningful Canada-United States environmental goods agreement could work. Wood is a fundmamental enabler of the shift to a low carbon economy. Given the long history of the bilateral dispute, the United States is unlikely to agree to a blanket removal of restrictions on forest products. To avoid misperceptions and ensure that the product is genuinely being used in a carbon reducing manner, Canada and the United States could negotiate a list of approved end-uses that would qualify for free movement under the agreement.

For example, wood destined for mass timber construction could be an end use. Why? Typically, large buildings in our cities and public infrastructure are made of steel and concrete. According to the OECD, these materials account for approximately 13 percent of carbon emissions globally. By building with wood – a material that sequesters carbon – substantial amounts of carbon are kept out of the atmosphere.

To operationalize the end use, a self-certification process subject to review by Customs and other authorities would be required. In terms of process, this would be no more complex than the rules of origin certification process used for imports under CUSMA and other free trade agreements.

An additional step that Canada and the United States could take is to commit to measuring the carbon impact of their trade remedy actions. Companies are increasingly documenting and publishing their carbon emissions, including downstream “Scope 3” emissions.

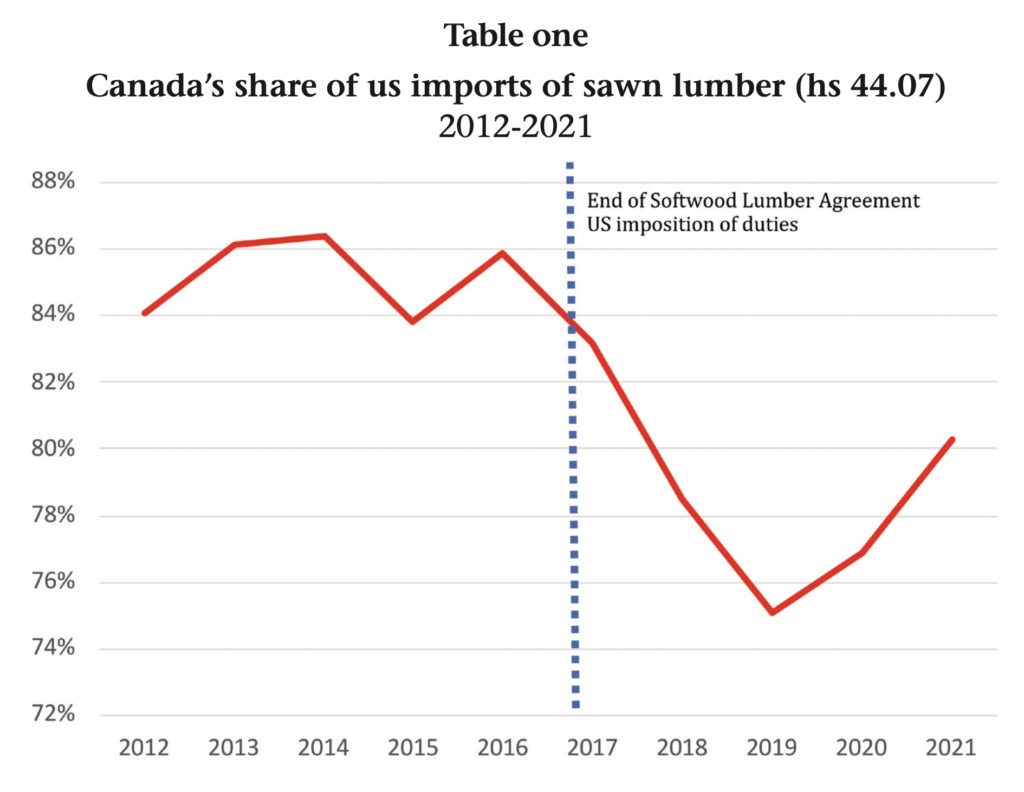

One seldom discussed fact is that trade remedy actions carry with them significant climate impacts. Take the case of sawn lumber from Canada. Table One looks at what happened to Canada’s share of the sawn lumber market after SLA2006 ended and tariffs were imposed. In short, it dropped significantly.

So, from where is the US getting its non-Canadian sawn lumber? The largest suppliers are Germany, Sweden, Brazil, New Zealand, and Chile. The additional carbon emissions generated from shipping sawn lumber from these distant lands is immense. Moreover, Canada has more than 40 percent of the forest land certified as sustainable globally, compared to single digits for these countries.

Today, Canada similarly finds itself at a crossroads. The challenge of our time is to build a low-carbon economy in a manner that strengthens, not weakens, its key sectors. Given forestry’s significant potential in this new world, the government of Canada should prioritize the pursuit of free trade in forest products for carbon reduction purposes. Finally, Canada and the United States could have something positive in the forest products world to agree on.

Eric Miller is President of Rideau Potomac Strategy Group and a Fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.