War and Peace, 2025: Canada, NATO, and a Rogue America

By Jeremy Kinsman

June 11, 2025

“They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”

Isaiah 2.4

In the garden of the United Nations headquarters in New York stands a sculpture depicting a man hammering a sword into a plowshare. It is the work of Soviet-era monumentalist Evgeny Vuchetich, creator of The Motherland Calls, the war memorial in Stalingrad (now Volgograd), site of the single deadliest battle in the history of war, and grave of more than two million.

The UN was founded in the wake of the Second World War’s unprecedented destruction and mass depravity, with the solemn oath of “never again.”

Alas, 80 years later, the world is metaphorically beating the plowshares back into swords. In the intervening decades, humanity survived the Cold War and its overhang of Mutually Assured Destruction and near-misses of nuclear collision. Wars still went on; proxy wars, wars of national liberation, violent coups, and eruptions of age-old enmities between peoples and sects. But for Western democracies, the violence of war itself was far away.

By 1991, the Cold War’s end held out the hope of global peace and cooperative consensus and even a “peace dividend.” Canadian governments jumped at it.

Their eagerness was not due to some Canadian-DNA aversion to joining armed struggles of principle. A memorial in Green Park by Buckingham Palace pays homage to “the more than a million Canadian men and women who passed through Britain” on their way to the 20th century’s murderous wars (from a population of only 7.9 million in 1914 and 11.3 million in 1940.) Canadians reaffirmed willingness to join a just fight in the name of freedom in Korea, and somewhat ambiguously in Afghanistan, when eager enthusiasts even pumped up the unconvincing notion of “a warrior nation.”

But Canada’s more blessed vocation throughout was always peacekeeping, in line with humanistic belief in the UN mission to provide security, not just to states, but to human beings. Since 1945, one of the two pillars of Canadian foreign policy has been to help construct and operate a universal rules-based multilateral system that could address humanity’s great shared challenges, including the propensity for war. The other constant pillar of Canadian foreign policy has been to solidify our privileged position as an ally and neighbour of the United States.

The adversary of much greater consequence to the US than Russia is China, America’s challenger for ‘number one’ global bragging rights, and for actual world influence.

Then in 2025, beneficial multilateralism and neighbourly bilateralism lost their reliability, one slowly and the other all at once.

Mark Carney’s rocket-like ascent to long-improbable electoral victory for the Liberal Party on April 28 received unprecedented international attention for a Canadian leader because of both Carney’s pre-existing role and reputation as a global financial player and his unequivocal recognition that President Donald Trump had utterly upended the longstanding presumption of Canada’s dependable bedrock relationship with the United States.

Trump’s economic belligerence toward Canada in violation of decades of mutually beneficial integration, his weaponization of tariffs despite the legalities of the CUSMA treaty he both signed and praised, and his threats of unilateral annexation of Canada as the “51st state” demanded, at the very least, a rhetorical reset. Carney’s defiant, sober resistance won the support of Canadians and admiration from skittish allies, themselves destabilized by Trump’s chaotic and disruptive activity, but seemingly unable to confront it openly.

They reeled from Trump’s blanket threats of destructive tariffs, but also from America’s arbitrary withdrawal of US leadership from the multilateral system that postwar Americans had led in designing. Trade policy scholar Eswar Prashad summed up the economic consequences of Trump’s rampage in The New York Times (June 5): “By shredding rules that have governed trade and by disregarding free trade agreements, Mr. Trump has undercut the entire rules-based order…Whatever their ostensible objectives, the Trump tariffs will make the world a poorer and more perilous place.”

On top of the costs of US tariffs to European and Canadian governments, the US is placing enormous pressure on these same NATO allies to boost defence spending to a new level of 5% of GDP, in part to accommodate US evacuation of responsibility for Ukraine’s defence.

Having begun to explore whether accommodation is possible with the US on bilateral issues, Carney will participate in three major summits in the last two weeks of June — the Kananaskis G7 (June 15-17), the Canada-EU meetings in Brussels (June 23), and the NATO summit in The Hague (June 24-26).

The Canadian Prime Minister’s summit role is unusually prominent, chairing the G7, being the key strategic partner in both trade and defence realignments at the Canada-EU Summit, and then being seen as something of a reformed free-rider with NATO colleagues.

Carney set out June 9th to update and elevate Canada’s profile and performance in defence strategy. Citing “threats from a more dangerous and divided world unraveling the world order,” he announced $9 billion in new spending to reach NATO’s 2% benchmark in 2025-26, and an increase in total spending to more than $62 billion this year.

Carney makes clear part of the “unraveling” is the new fact of basic US unreliability and that Canada is not making this unprecedented increase in defence spending just to placate US pressure. Nor is it just to meet NATO’s longstanding defence-spending goal of 2% of GDP for members, which has now been overtaken by a 3.5% benchmark, closing in on 5%. He intends it to help diversify our vital relationships, to lessen Canadian dependency on an America that he insightfully assesses is “beginning to monetize its hegemony, charging for access to its markets and reducing US relative contributions to our collective security.”

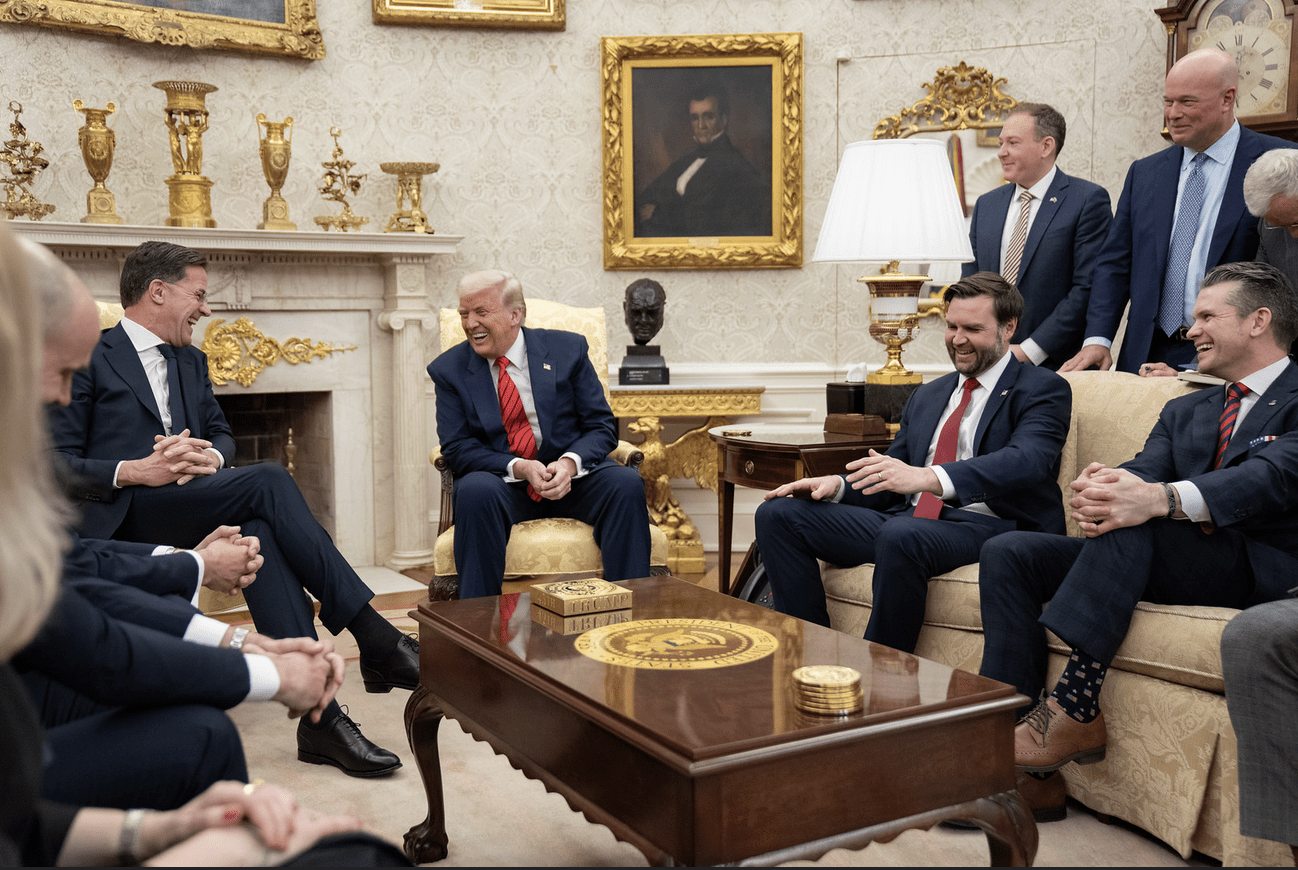

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte meeting with Donald Trump on March 13, 2025/White House photo

NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte meeting with Donald Trump on March 13, 2025/White House photo

The political consequences of that are seismic. Under Donald Trump, the US has gone rogue, not only regarding its institutions and arrangements with allies, but in its abandonment of the values, ideals and dependable motives that made it a soft-power superpower for more than a century, as well as the shared affinities that defined its foreign attachments.

G7 and NATO allies are agitated by growing evidence that Russia and China (and various other rogue actors) believe they can act with impunity from weakened international institutions and councils. But they are mostly agitated by the actions and attitudes of their long-standing American partner, who suddenly hews more closely to that autocratic model than to its 250-year history as a democracy.

Some participants in the G7 and NATO Summits are hoping to preserve the appearance of unity with the US by ducking or papering over the most divisive issues. But the whole purpose of the G7 is to concert over differences, not to evade them. Chairman Carney will not try to negotiate a consensus communique, but only a Chairman’s Statement, as has been done in some previous G7s, which may well set out the differences in black and white.

A week later, the NATO Summit in The Hague will feature the US President’s demand that the 32 NATO members now commit to spending 5% of GDP on military budgets. The US will also try to influence G7 and NATO partners to resist any temptation to strengthen their trade with China, to the point of threatening penalties on those which do. Though members, including Canada, are willing to pledge more defence spending, they won’t accept 5% except in aspirational terms, and won’t agree to line up behind America on China, even though China’s aggressive intentions in the South China Sea, and potentially in the Arctic, are unsettling.

All agree that the world is in transformation. US hyperpower dominance is a thing of the past, in large part because of the remarkable economic rise of China and India. When the G7 first met a half-century ago its members accounted for 70% of world GDP. Today, it is 44%. But belying Trump’s claim the US economy has been “victimized” by others, the share of the US has remained constant at about 26% of the world’s GDP, while the GDPs of other G7 countries with slower growth rates have seen a relative shrinkage as a portion of the global GDP pie.

The remaining 1/3 of the world economy is accounted for by the countries of the Global South. Only a relative few are quite rich, mostly because of oil and gas, while sub-Saharan African countries have basically been in per capita GDP standstill for 50 years. Trump’s US has now all but abandoned the development field, shutting down USAID and other beneficial outreach agencies, with dire consequences on health, welfare, and related science, around the world.

In 2025, beneficial multilateralism and neighbourly bilateralism lost their reliability, one slowly and the other all at once.

This month’s summits occur as what Carney calls Russia’s “barbaric invasion” of Ukraine persists. The Trump administration, apparently indifferent to Russia’s acts and threats, seems willing to leave material and military support for Ukraine within the alliance to Europeans and Canada. Meanwhile, Russia’s NATO-hating president is building a 1.5 million strong military force to deploy as a concrete threat to Western Europe and its allies. But NATO allies are uncertain if the US would today honour its NATO Article 5 obligations to defend any NATO member attacked by Russia.

The adversary of much greater consequence to the US than Russia is China, America’s challenger for “number one” global bragging rights, and for actual world influence. Despite America’s retention of vast leverage over the global economy, its huge military assets, its alliances, and tech achievements, China is demonstrating superior capabilities in the strategically critical area of artificial intelligence, while accounting for more than 30% of global manufacturing, twice America’s, with twice as many countries that count China as their principal trading partner.

The fact is that the Trump administration is advancing a different worldview than America’s democratic allies, perhaps toward new geopolitical groupings around three dominant spheres of influence: the US in the Americas, China in Asia, and Russia in Eurasia. This is obviously anathema to US allies from Europe, Japan, and especially Canada.

That is why the Canada-EU Summit is so important. Carney’s outline of new defence investments and intentions, in cyber, AI, in modern capital equipment renewal, in joint procurement and defence infrastructure, and in shared projects, including especially in the centrally emphasized Arctic, are all of direct interest to EU strategic partners. Carney intends to advance Canada’s participation in the EU’s ReArm Europe program. Separate discussions are ongoing on participation in Germany and Norway’s joint program to build a dozen submarines. Australia is already a partner on Arctic early warning systems. Canada should engage the Danes and other Arctic Council Europeans, on security of Arctic passages through Canadian waters to Greenland.

Though Canadians regret the US threats to Canada, some believe we can’t deny the logic of our geography, and lean to accommodation to US demands, short of absorption. But our geography has variable opportunities, notably closer integration with Europe, not just on defence projects, but on strategic geoeconomics. We shall always be geographically compelled to valourize and nurture our prime US relationship, but the events of recent months hold out the opportunity of like-minded relationships that can strengthen our global vocation.

The strident US reaction to Canada’s sanctioning, jointly with the UK, Norway, New Zealand, and Australia, of two Israeli government ministers for inciting violence against Palestinians is another indication that the official American view today is not ours — on our sovereignty, on values, and on human rights.

Time will tell whether the US will revert to its values and its historic evolution as a democracy, partner, and leader.

As to the prophet Isaiah, his hopes for humanity remain ours, though Canada seems readier now to show belief in being prepared for war as the best way to deter it.

Policy Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman served as Canada’s ambassador to Russia, high commissioner to the UK, ambassador to Italy and ambassador to the European Union. He also served as minister at the Canadian embassy in Washington. He is a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.