Weepless in Wyoming

Douglas Porter

August 26, 2022

Deprived of much in the way of real economic news, markets spent most of the week in keen anticipation of Chair Powell’s Jackson Hole address. The much-hyped speech—and it is, after all, only a speech—made some minor hawkish market waves, but fell somewhat short of the modern-day Gettysburg Address in its sweep. (Random digression: Four score and seven years ago—1935—the Bank of Canada came into existence.) The speech frankly tilled little new ground, acting more as a cudgel against those looking for a fast Fed pivot, a blink, or rate cuts in 2023. After spending most of the week moving higher, bond yields thus took another step up in the wake of Powell’s remarks, with two-years leading the way to above 3.4% (up almost 20 bps from a week ago), while 10s wobbled around 3.05% (2.97% a week ago). Stocks ended the week on a downswing, while the U.S. dollar finished slightly firmer after rising above parity versus the euro.

Arguably the most telling line from Powell’s remarks was: “The historical record cautions strongly against loosening policy prematurely”. As we indicated last week, the biggest debate or disagreement between market pricing and Fed speakers in recent weeks had been on rates in 2023—with the markets expecting cuts, and officials warning rates would need to stay restrictive for a lengthy period of time. In a nutshell, Powell pounded the theme home that there is still work to be done and the job will take time. Some key speech clips:

“Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth”

“There will very likely be some softening of labor conditions, and some pain for households”

“Neutral is not a place to stop or pause”

“Restoring price stability will likely require maintaining a restrictive policy stance for some time”

“The Fed must keep at it until the job is done”

One new wrinkle in the address was a reference to “rational inattention” on inflation expectations. That is, when inflation is handily under control, consumers and business can rationally ignore inflation, an ideal world for policymakers. Sadly, we are pretty much on the other side of the spectrum currently, with monthly inflation readings the number one news item in many major economies. And, Powell asserts that the longer attention remains focused on inflation, the harder it will be to eradicate—and thus the main conclusion that they simply can not back down early, even amid some serious economic pain. Paraphrasing Tom Hanks, there’s no crying in monetary policy.

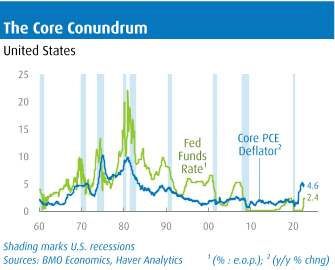

While the lead-up to the big speech was generally quiet, the modest slate of U.S. economic releases this week was mostly encouraging, flashing signs of cooling inflation and stable growth. Perhaps most important was Friday’s news that the core PCE deflator nudged up just 0.1% in July, trimming the annual increase to 4.6%, from a February peak of 5.3% and the slowest pace since last October. At nearly 4 percentage points below the current headline CPI reading (8.5%), this measure of inflation almost seems to be from a different economy. Yet it is ultimately the Fed’s favoured gauge, and suddenly the task of bringing it closer to the 2% target seems less daunting. Mildly reinforcing that point was the revised University of Michigan consumer survey, which showed five-year inflation expectations a tick lower at 2.9%.

On the growth front, most signs suggested that activity stabilized in the summer after the surprising back-to-back quarterly declines in GDP to start the year. A modest 0.2% rise in real consumer spending, a much narrower trade deficit, solid gains in capital goods orders and shipments, and a more recent retreat in jobless claims all suggest the economy churned out mild growth. No doubt, the housing sector remains in full-blown retreat, with new home sales dropping to the lowest since early 2016 (even below pandemic lows!) and pending sales heading for levels last seen more than a decade ago. Even so, the early read on Q3 is for a mild uptick in GDP after the (revised) 0.6% drop in Q2. Further batting away thoughts that the economy was in recession in the first half of the year was news that real gross domestic income rose at a 1.6% annualized pace over that period—modest, for sure, but not a downturn.

It was an even lighter week for Canadian economic news, with precisely no top-tier releases or speeches. Ahead of next week’s Q2 GDP results, where a solid 4.5% advance is expected, the early read on July looks soggy. Flash results on both wholesale trade (-0.6%) and manufacturing sales (-0.9%) were down, echoing an even bigger setback in retail (-2.0%), and a drop in hours worked. Still, job vacancies hit a new high above 1 million in June, wages are pushing higher (up almost 5% y/y), and consumer confidence actually managed to nudge up in August. Firmer consumer sentiment was also reported this month in each of the U.S., France, and Italy, with the uptick likely due to the pullback in gasoline prices, at least in North America.

But the underlying resilience in U.S. economic activity raises a pair of key questions for policymakers. First, have rates risen enough to seriously chill growth? And, second, how much does growth need to slow to seriously chill inflation? Harkening back to the key quote from Powell above, the historical record also shows that in every cycle of the past 60 years, Fed funds have needed to rise above the core PCE deflator for inflation to meaningfully crack (Chart).

At this stage, the conventional wisdom—among the markets, economic forecasters, and the Fed itself—is that short-term rates will top out at somewhere between 3.5%-to-4.0%. Yet, that’s still well below core inflation trends, even with the recent moderation. Either the cozy consensus is wrong on terminal, or core inflation will somehow moderate further on its own, bringing it below short-term interest rates. The great hope is that just as there were a wide variety of special factors boosting inflation in the past 18 months, some of those special factors may now go in reverse—notably supply chain snarls and overheated demand for many goods. The Fed can only hope.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.