What Gorbachev Did, for All of Us

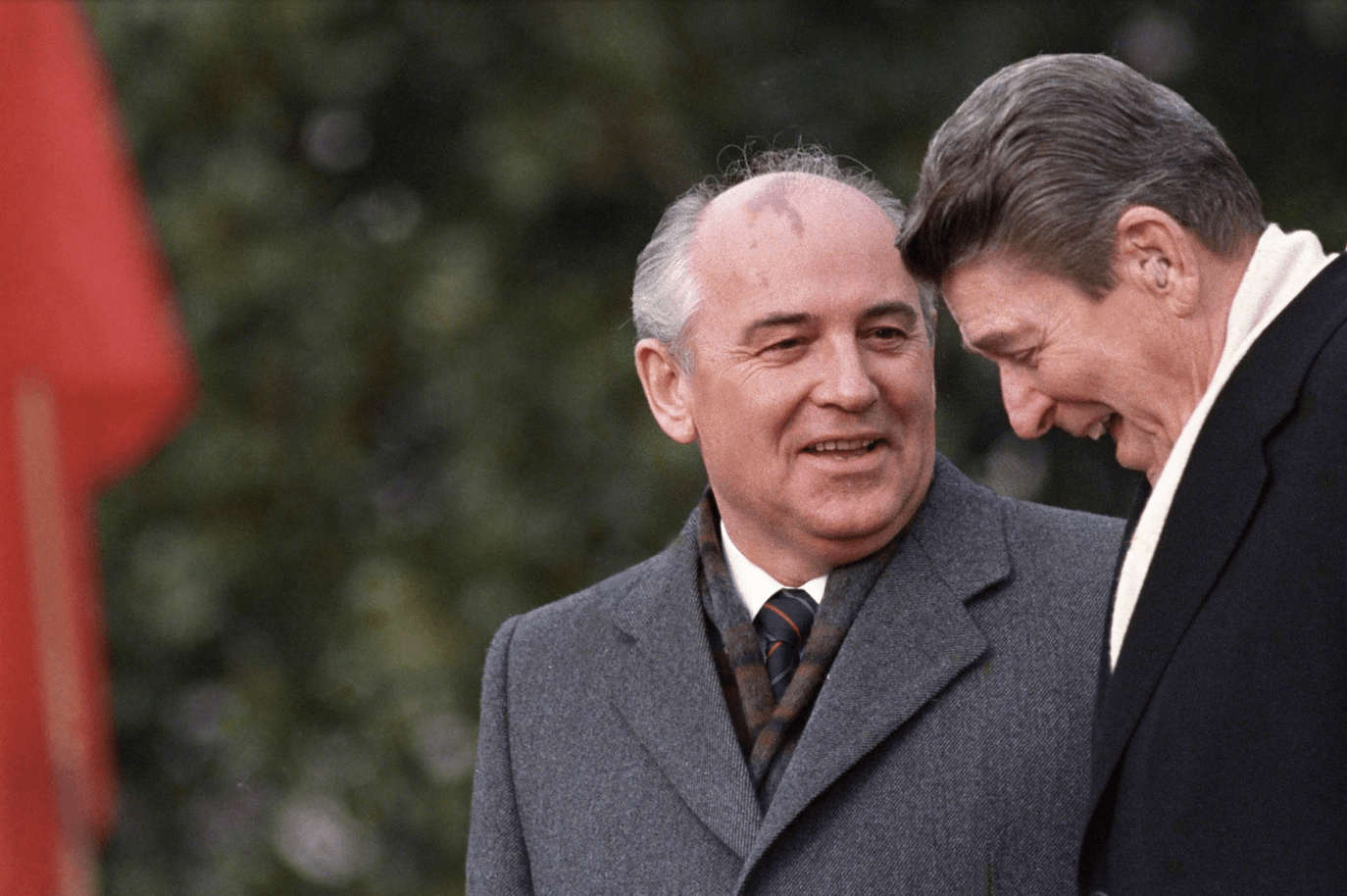

Boris Yurchenko/AP

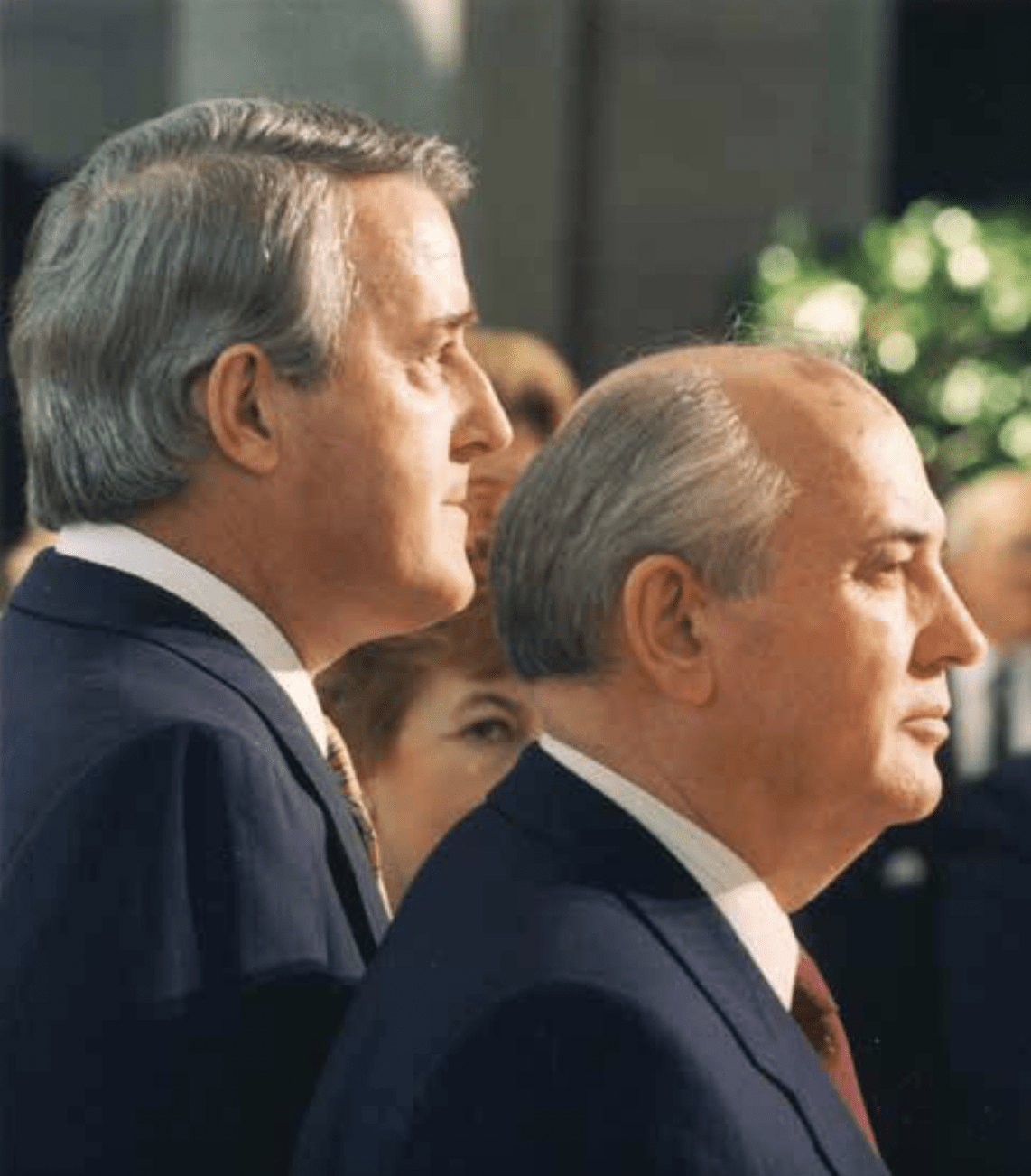

Boris Yurchenko/AP

Jeremy Kinsman

August 30, 2022

In one hundred years, if the world is still alive and relatively well, Mikhail Gorbachev will be remembered as a colossal figure who changed the world by bringing the citizens of the Soviet Union out of their traumatizing and terrible twentieth century. Though a convinced socialist, he ended communism.

Gorbachev, who died on Tuesday at 91, introduced his fellow citizens to freedom.

He ended the Cold War. A man of peace, he sought a “common European home.” He enabled the United Nations Security Council to function cooperatively for a brief few years the way it had been roughly conceived by its idealistic post-war founders, who had constructed the UN from the ashes of World War II in the spirit of “never again.”

That a successor, Vladimir Putin, has undone those achievements by turning the free Russia he inherited back into a police state and by invading Ukraine will hopefully be inscribed in history as a blip, if, as seems likely, Putin’s gamble to reassert imperial Russian control fails, as it must.

Gorbachev, for all his explanation of purpose made in long,monologuish meetings with his peers on the world stage — notably, US presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, French President François Mitterand, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, and Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Brian Mulroney and others — was deeply appreciated by them, but not adequately understood. They could not relate to his almost impossible challenge of completely de-controlling a controlled society, and to invert almost every officially ordained tenet of public and private life. They got to tinker at their society’s edges. He utterly transformed his.

The Americans believed that in doing so, he was pragmatically conceding that the USSR couldn’t compete with the United States as an economic system. So, they concluded, he threw in the towel. “We won. Get over it,” the shallower American personalities said.

I found Gorbachev in the hotel lobby, surrounded by cleaning ladies mesmerized by his presence, touching his suit as their antecedents might have once yearned to touch the coat of a tsar.

We never really got that Gorbachev was taking an essentially moral decision, as counselled by ex-Ambassador to Canada Aleksandr Yakovlev, to place glasnost first, to remove from the shoulders and consciousness of citizens the legacy that three-to-four generations of terror had imposed. He did it first to free them to be able to mobilize the commitment to entirely transform their economic and social system. Deng Xiaoping in China thought he was crazy and did the opposite, proceeding first to economic reforms, and only when stability was achieved, to contemplate political reform. (His successor today — like Putin — seems to have abandoned that contemplation).

Hardliners in the security community in the US always mistrusted Gorbachev’s intentions. US presidents began to write off Gorbachev and the consequences of letting him down. The USSR — and, after 1991, Russia — became relegated from superpower status, though some, notably Mulroney, worked hard to bring the USSR and then Russia into the G7 family directorate, out of a genuine belief that Gorbachev’s bravery and vision had given the world a real shot at a new cooperative world order. When Gorbachev appeared as a guest on the veranda of Lancaster House at the London G7 Summit in June 1991, the officials lunching on the lawn below rose as one in a spontaneous ovation. I was one of them, and we knew he had changed the world.

Alas, we didn’t know then how gravely his position was threatened at home by the displaced and plotting old guard in his administration; the equivalent of the US security community hawks in theirs. We had little remedial advice to offer to right the Soviet economic boat, which was fast sinking, with millions and millions of vulnerable citizens in the direst of straits. Our economic expertise had counselled them just to open their markets and de-regulate, with the blithest of advisors advising “shock therapy.” Its effect amounted to much more shock than therapy. We didn’t have a clue about the depth and width and behavioural implications of Russia’s economic transformation. So, when his democratic rival, populist Boris Yeltsin, couldn’t displace Gorbachev as USSR president, and so broke up the USSR itself, we were sad for Gorby, but overall pretty positive that all was for the best.

Not so, for Mikhail Gobachev. He retreated to his new foundation, and Mulroney made sure Canada contributed to its well-being.

He and Raisa consoled each other until she died in 1999. He was a fortunate person who had been blessed by a great love. But during that time, in Russia, his reputation sank like a stone because of the chaos his changes were seen to have ushered in, and because it served both the corruption and political purposes of his ultimate successor to belittle Gorbachev’s legacy.

And yet…he had broken the grip of what had become after 1917 a murderous state enterprise which had succeeded centuries of autocracy. When Foreign Minister Barbara McDougall visited Moscow in January, 1993, she gave an address at the Diplomatic Academy. We invited Gorbachev, then the ex-president. He said he could only attend the reception afterward. I was alerted that he had arrived while the proceedings were still going on, and hastened to greet him. I found Gorbachev in the hotel lobby, surrounded by cleaning ladies mesmerized by his presence, touching his suit as their antecedents might have once yearned to touch the coat of a tsar.

Though Gorbachev was a forceful personality, he was no tsar. He said later that he couldn’t have been because he wasn’t up to using force against people. That moral bottom line will be remembered to his eternal credit, in contrast to the brutality of the present Kremlin incumbent.

In time, Russians will need to remember and understand all that has happened both to them and for them. Then, they will see how much Gorbachev contributed to the “for” side.

And so should we, for what he did for all of us.

Contributing Writer Jeremy Kinsman served as Canadian Ambassador to Russia from 1992-96, as well as Ambassador to Italy, High Commissioner to the UK and Ambassador to the EU. He is currently a Distinguished Fellow of the Canadian International Council.