What Kind of Populist is Pierre Poilievre?

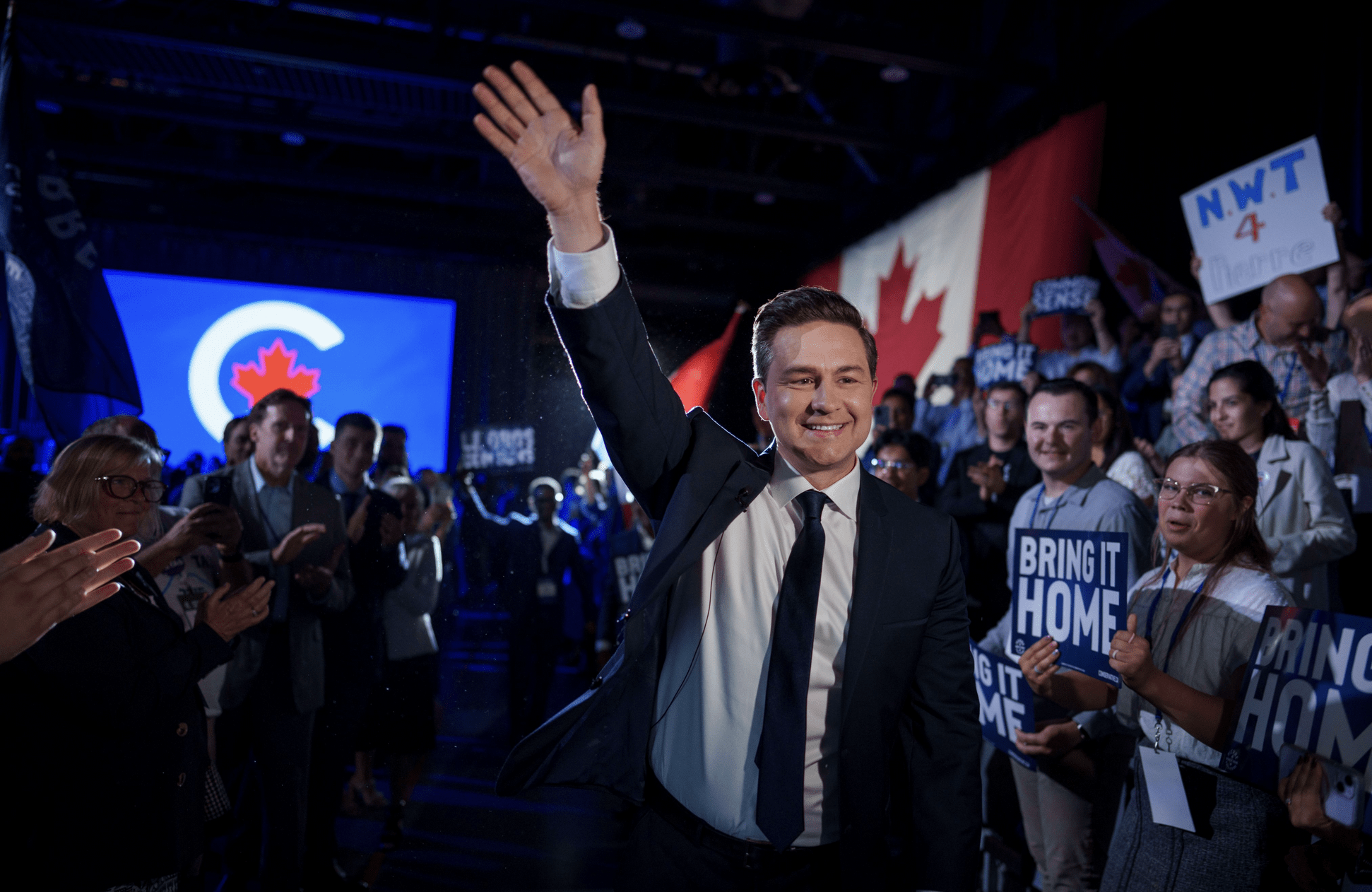

Pierre Poilievre/X

Pierre Poilievre/X

By Yaroslav Baran

February 19, 2024

When Pierre Poilievre began characterizing himself during the 2022 Tory leadership campaign as the next prime minister of Canada, it was an aspirational applause line. Today, it appears to be a probability. Public opinion polling has revealed a dramatic shift over the last year, with the Conservative Party of Canada steadily gliding toward unquestionable dominance in federal voter intention. How did this happen? Was it an accident of fate, or the shrewd harnessing of public concerns and priorities?

A short ten months ago, Canada’s two main parties were in a dead heat, suggesting a coin-toss outcome if an election were to have been held – with perhaps a slight edge to the Liberals whose geographical voter distribution tends to more efficient. Today’s polls show a consistent double-digit lead for the Tories, with seat projections suggesting a 99 percent likelihood of a Conservative majority, and a one percent chance of them winning a mere minority. Liberal re-election under Justin Trudeau is no longer – at present – considered a statistical plausibility.

True, polls do change – witness the shift from a year ago to now. But given the underlying issues driving the change in voter intension – strong public anxiety over the cost of living and loss of purchasing power, and in particular a grave concern over home and rent affordability – a sound political analyst will conclude it is less likely the polls would narrow back as easily as they spread. Even if the Bank of Canada were to defuse inflation as an issue by returning to its target range of one to three percent, the last four years’ erosion of purchasing power would still not be fixed. Moreover, the fundamental disequilibrium between supply and demand for housing is a minimum decade-long venture to fix.

This dramatic shift has understandably cast a spotlight on Canada’s would-be prime minister: Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre. Often cast as a “populist” – a term with different interpretations in Canada’s political culture – his opponents have seized on the “p word” to try to demonize the right’s new leader and halt his rise by linking him to Donald Trump and the MAGA-movement.

Is this tactic, which was previously deployed against the Conservatives in both the 2019 and 2021 elections, fair? Is it accurate? This is an appropriate moment to unpack Canada’s shift in voter intention, and also to assess Canadian populism for an accurate read of how Pierre Poilievre fits into it. Is he “Canada’s Trump” as his opponents try to cast him? Is he even a populist? What is Canadian populism? What does the term even mean – overall, and in a Canadian political context?

While often used as an implicit slur connoting demagoguery, the term itself has a nobler, more democratic, heritage. The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary defines populism as “a type of politics that claims to represent the opinions and wishes of ordinary people. It is characterized by its focus on the general populace and often positions itself against established elites.” The Cambridge Dictionary adds: “In simpler terms, it is a political movement or philosophy that appeals to common individuals rather than adhering to traditional party ideologies.”

By most scholarly accounts, the term itself originated in the 1890s, as a self-designation of the left-wing American People’s Party, to connote an approach to politics that challenged the elites. University of Sussex political scientist and populism scholar Paul Taggart has referred to populism as “one of the most widely used but poorly understood political concepts of our time.”

In the Canadian political experience, perspectives on populism differ according to the historical experience of the region. In political “Eastern Canada” – the two provinces of Ontario and Quebec that have traditionally dominated Canadian politics and political economy via the Laurentian Consensus – populism is often seen as an outside force challenging the hegemony of Upper and Lower Canada and the institutions therein.

Against a backdrop of British political culture that focused on order, tradition and institutions, we can understandably derive the common assumption within intellectual bubbles such as the Parliamentary Press Gallery, or “Official Ottawa”, that populism is an inherently negative force – barbarians at the gates.

But outside the traditional Canadian power base, it’s a very different story steeped in a deep and compassionate political tradition.

To understand Pierre Poilievre, we need to understand that he cut his teeth as an acolyte of Preston Manning – the former MP and political reformer (and Reformer). Manning is the son of prairie-populist Alberta premier Ernest Manning — Social Credit party premier between 1943-1968 – who had, himself, been an understudy of his immediate predecessor, William “Bible Bill” Aberhart, the intellectual founder of the Social Credit movement whose “power to the people” appeal defined his own tenure as premier from 1935-1943.

The Conservative Prairie populism of Aberhart, the Mannings and John Diefenbaker was, in fact, similar to its centre-left equivalent personified in Tommy Douglas of CCF and later NDP fame. It had far more in common with the Prairie coal miner labour movement than with the private clubs and powdered wigs of British Toryism.

The critical difference between the Canadian Prairie populist tradition (right or left), compared with American counterpart movements, is that Canadian populism is rooted more in communitarianism than libertarianism. It focuses on institutional reform, access and democracy, not iconoclasm.

Canadian populism is traditionally a benevolent movement focused on the restoration of confidence in institutions – not on tearing them down. It doesn’t necessarily call for the abolition of the Senate – it seeks to make it elected. It seeks to restore free speech on university campuses (traditionally its bastions), rather than shaping those same campuses to try to drive a social or ideological agenda. It aims to remove barriers to access government – from procurement simplicity that weeds out cronyism, to “plain language” government forms for the citizenry.

In short, it is anything but an anti-democratic movement; it tends to be an anti-anti-democratic movement. It sought to protect the common citizen from the excesses and privilege-abuse of big banks, government, police, and economic cartels. Power to the common person. This is the political tradition in which Pierre Poilievre was schooled.

Ironically, historically, in the few cases where Canada did experience “torches and pitchforks” movements, they were not in the populist heartland, but rather in the “establishment” cities of Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg, in its heyday as a Midwestern financial centre: The Lower Canada Rebellion of 1837, the Upper Canada Rebellion of the same year, and the Winnipeg General Strike in Canada’s then-third largest city in 1919.

It would be a mistake to take the lazy evaluative approach of assessing Pierre Poilievre and extrapolating that he is a replica of Donald Trump.

In practical application, there is perhaps no better metaphor to understand Canadian populism than Preston Manning’s oft-used parable comparing public anxiety to a “rogue gas well”: he famously warned that one of the most dangerous scenarios in the oil and gas industry is to have a sudden pressure buildup underground. It requires a reliever-well being drilled carefully, laterally, delicately, to slowly ease the pressure – or else things go kaboom. Public political anxiety is the same, he argued. It can be carelessly incinerated with a match, or one can try to carefully tap the pressure and slowly bring it down to normal.

Poilievre’s “common sense” mantra is derived directly from his indirect political mentor Manning, who spoke of “the common sense of the common man”. But the young former Reform youth activist Poilievre also had his politics tempered by the pragmatism of experience in the Harper cabinet. While Harper himself was largely forged in the smithy of Manningism, his tenure as prime minister for nearly a decade was characterized by a managerial practicality rather than ideology.

Poilievre sees current social tension as the result of the careless approach to the rogue gas well. Canadians are anxious over pandemic lockdowns, loss of livelihood and restrictions on their ability to provide for their families? The last thing you do is “other” them, cast them as villains, blame them for social discord caused by public policy – particularly if the anxious are less prosperous and economically secure than those doing the finger-wagging. His approach with the trucker convoy is an example of trying to tap that pressure-well from the side: validate the complainants as real people with real concerns, make them feel seen and heard and human, and try to bring down the pressure. Does this mean recognizing a Q-Anon charlatan as the real queen of Canada? Of course not. Is it a validation of a random rogue manifesto declaring a new government between the Senate, governor-general and the Street? Certainly not. But his approach did seek to defuse an “us-versus-them” – elites versus the peasants – dimension in politics that only festers and breeds lingering resentment and alienation.

Canadian conservatism has traditionally been supportive of immigration, pluralism and multiculturalism. Our history has forged a consensus on the question, that has also fortunately made all our political traditions resilient against xenophobic tendencies.

But what does this mean for foreign policy? As we witness the US Republican Party eat itself whole over competing narratives about Ukraine (the true versus the Kremlin propaganda versions), we cannot help but wonder if nativism is spreading north.

The fact is that whenever economies weaken, nativism and isolationism grow in appeal. But in the Canadian conservative tradition, the fundamental abhorrence of moral relativism ultimately overrides any nativist tendencies that ride with populism and a sagging economy.

It needs to be underscored that the Canadian Conservative government of Brian Mulroney recognized Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union when US president George Bush was dithering. And following the invasion of Crimea, it was Canadian Conservative foreign minister John Baird who formed the informal “three wise men” trio of Swedish foreign minister Carl Bildt and Polish foreign minister Radoslaw Sikorski to pull up NATO and challenge it to follow a principle-based approach to Russia’s stealth invasion.

While we might debate the record of defence spending from government to government, the Conservative tradition has never opposed it on principle, and has always sought a foreign and defence policy that seeks concert with like-minded democracies rather than just broad multilateralism writ large.

Are there elements of isolationism in today’s Canadian conservatism? It is more correct to say they exist in Canada, period. You see it in “Canada first” conservatism, in intellectual relativistic liberalism, and in the “anti-imperialism” left. All three strains of all three political traditions are natural injection points for Kremlin or Chinese Communist Party propaganda. But a natural entry point does not mean an expanse of fertile soil.

Mainstream Canadian foreign policy – be it that of Liberal or Conservative governments – has tended to follow not only Canada’s founding principles of “peace, order and good government” but also our national values of “freedom, democracy, human rights and the rule of law.”

It would be a mistake to take the lazy evaluative approach of assessing Pierre Poilievre and extrapolating that he is a replica of Donald Trump.

The latest manifestation of conservative populism must be evaluated in its Canadian context and political tradition. Validating the powerless, giving voice to the voiceless, recognizing the “othered”, and standing up to abuse of power – these are the hallmarks of Prairie populism, both left and right, that have tempered Canadian politics and history over decades, and that have forged a uniquely Canadian expression of populist politics. Pierre Poilievre hails from this tradition.

Yaroslav Baran is a partner and co-founder of Pendulum, a political analysis and communications consultancy. He served as communications director for Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s 2004 leadership campaign, and ran Conservative Party communications in the next three elections..