What’s Next? Monetary and Fiscal Policy in 2023

Kevin Page, Azfar Ali Khan, and Matthew Mcgoey

December 15, 2022

What’s next?

Is there an end in sight to the recent period of economic turbulence?

“Is the future made of the same stuff as today?”, to quote the French philosopher Simone Weil, or are we on the threshold of a new global order and economic period shaped by a pandemic and geopolitical tension?

Is Canada well-positioned to meet the myriad of policy challenges of a post-COVID world?

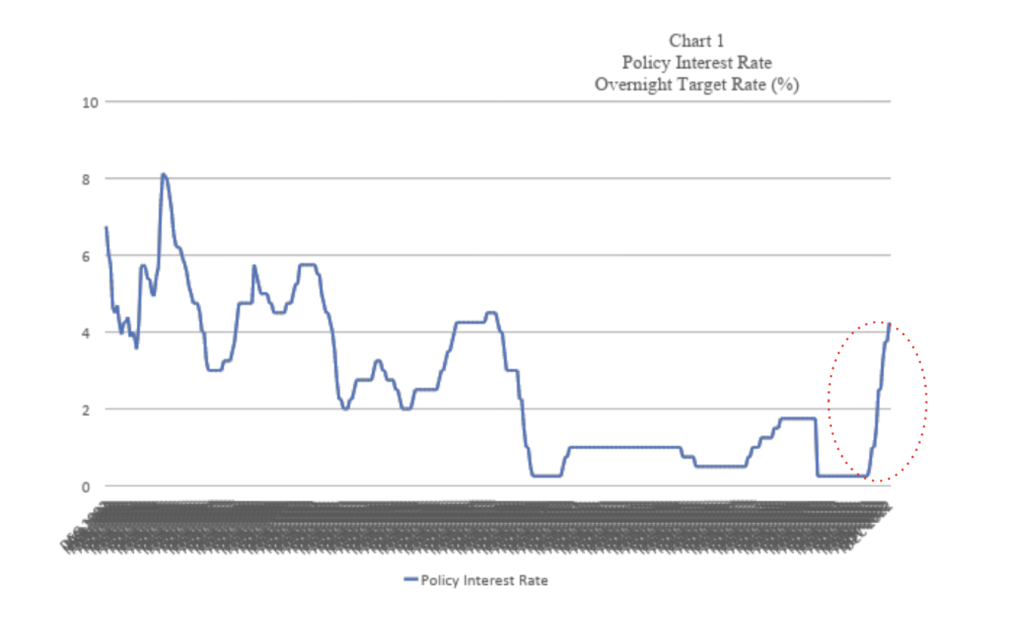

On December 7, Tiff Macklem, the Governor of the Bank of Canada, announced a 50-basis point increase in the policy interest rate to 4.25 percent. In 10 months, the benchmark interest rate for household and business rates increased 4 percentage points. It is the largest and quickest increase in the policy rate since the Bank of Canada started inflation targeting in the early 1990s (Chart 1).

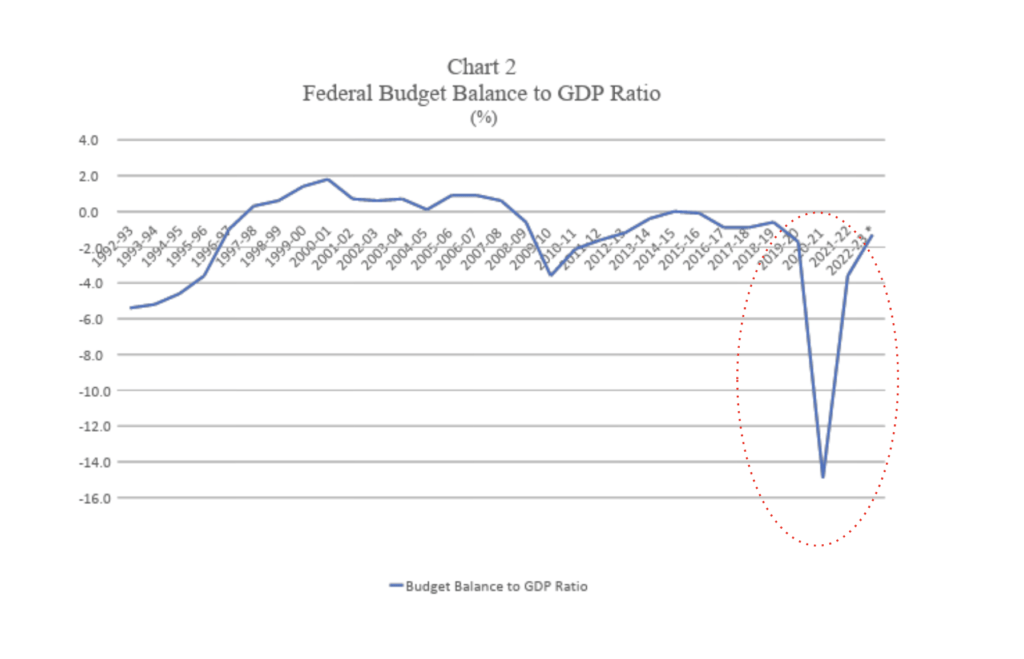

On November 3, 2022, Chrystia Freeland, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister, delivered the Fall Economic Statement. The budgetary deficit peaked at $328 billion (14.9 percent of gross domestic product, GDP) in 2020-21, fell to $90 billion (3.6 percent” of GDP) in 2021-22 and is projected to be $36 billion (1.3 percent of GDP) in 2022-23. It is an unprecedent fiscal trajectory – up and down (Chart 2).

Monetary and fiscal policies have been on a roller coaster. We need central banks and governments to help stabilize economies that have been destabilized by global events. In less than 15 years, the world has faced three significant shocks – a global financial crisis (2008), the COVID pandemic (2020) and the Russian war on Ukraine (2022). With imperfect foresight, stabilization policies can produce nasty side effects like high inflation. How, when or ever will we get off this roller coaster?

In early 2020, with no vaccine available to address the COVID virus, Canadian governments and public health officials implemented strict social distancing rules. In two months, the Canadian economy (real GDP) fell almost 18 percent.

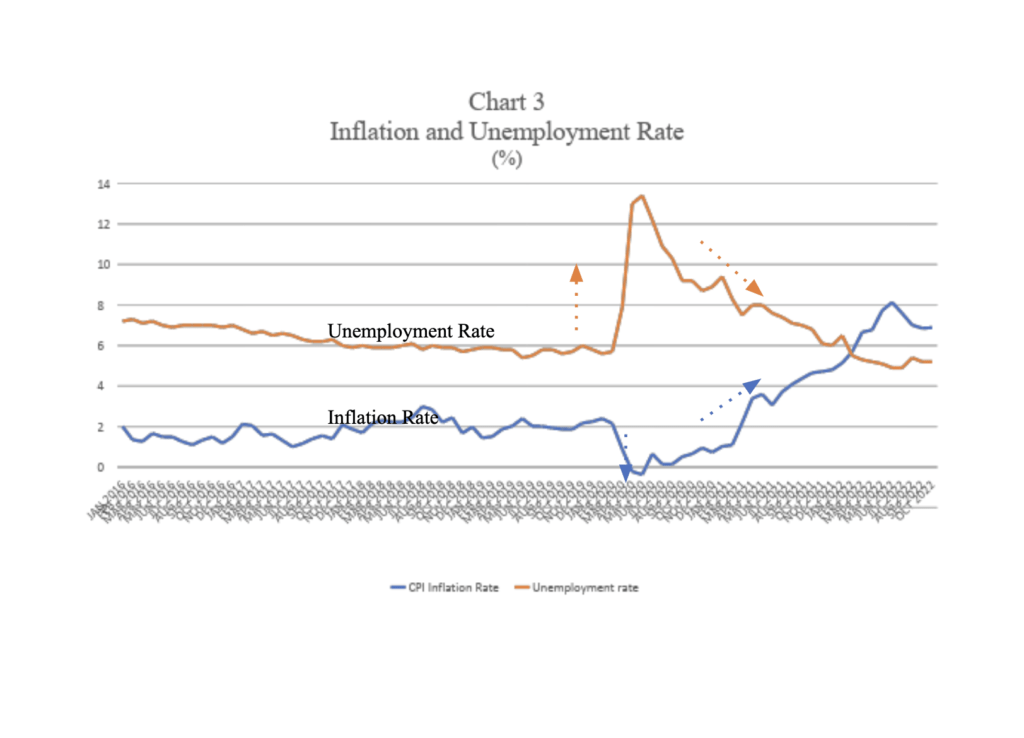

Unprecedented. In four months, the unemployment rate went from 5.7 percent to 13.4 percent. The consumer price index (CPI) year-over-year rate of inflation fell from 2 percent to -0.2 percent in three months. It was a hyper turbulent environment that threatened to overwhelm our public health and economic systems (Chart 3).

Canada’s policymakers are now looking at primarily bad to ugly planning scenarios. The bad scenarios are really best-case potential outcomes given the large increases in central bank policy interest rates in Canada and around the world.

Governments and central banks responded with massive supports. The economy was stabilized. There were hundreds of billions of dollars in both direct fiscal supports and liquidity measures. The monetary base of the country increased by hundreds of billions of dollars as the central bank added government bonds to its balance sheet to help finance the crisis response. Household and corporate net savings rose dramatically with the increase in current transfers. In basketball parlance, the zone was flooded with cash.

With vaccination and the end of social distancing, the stage was quickly set for a strong rebound in the economy. Yellow policy flags were raised in the fall of 2021 with large month-to-month increases in the CPI. Policy makers questioned whether this was more transient or permanent in nature? In retrospect, increased demand was pressing up against COVID related supply challenges. High and rising inflation and inflation expectations were being embedded into the COVID recovery.

The stage was reset (and not in a good way) when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Fuel was added to inflation pressures. Commodity prices, particularly oil, gas, and grain prices spiked as the war negatively impacted global supplies. The year-over-year increase in the Canada CPI peaked at 8.1 percent in June 2022 before declining to just under 7 percent in the fall. The new worry is the upward drift in the core rate of inflation.

Canada’s policymakers are now looking at primarily bad to ugly planning scenarios. The bad scenarios are really best-case potential outcomes given the large increases in central bank policy interest rates in Canada and around the world. The outlook is fragile. Risks are asymmetric. There are more downside risks in the short term than upside.

The interest rate increases were designed to manufacture a growth slowdown to reduce inflation. The challenge in Canada is high household debt. High inflation and rising interest rates over the past year will hit consumers hard. Consumer credit and mortgage liabilities relative to disposable income sits at 175 percent, up 30 percentage point since the start of the 2008 global financial crisis.

The bad scenarios are weak growth (soft landing) or a shallow and short recession in 2023. The Finance Fall Economic Statement included both outlooks.

The “ugly” scenario was not presented in either the Finance or Bank of Canada outlooks and would likely be a significant recession more reminiscent of output declines and unemployment increases of past recessions in 2008 or in the early 1990s or 80s. High household debt increases the risk of a more severe recession.

At this juncture, all three planning scenarios are still in play. Leading indicators (e.g., business surveys, purchaser manager indices, consumer spending, housing prices, etc.) suggest the Canadian and other advance economies are slowing down.

Bottomline – there is more economic turbulence on the horizon.

Mohamed El-Erian , President at Queen’s College at Cambridge University, makes the case in Foreign Affairs magazine in November that it would be a mistake to see the economic challenges ahead as both temporary and quickly reversible. A return to macroeconomic stability, strong growth and low inflation after the pending recession is not baked into the cake.

El-Erian highlights three potential forces to watch in the post COVID economy – insufficient global supply forces shaped by geopolitical tension; the end of easy money policies by central banks, and increasing fragility of financial markets. All three forces represent structural headwinds that should not be ignored by policy makers.

Early in 2023, Canadians will get another policy rate announcement and monetary policy report by the Governor of the Bank of Canada on January 25, and the tabling of Budget 2023 by the federal government. The stakes are high. Notwithstanding a turbulent global economy, Parliament, Canadians and financial markets want greater clarity on policy direction.

On monetary policy, it is likely we are at or near the peak of the current rising interest rate cycle. If we get a few more releases of declining CPI inflation rates (as expected, barring another economic shock), it will be difficult for the Bank of Canada to continue to raise its policy interest rate while the economy is in a recession and the unemployment rate rises. Expect the central bank to continue its policy of balance sheet normalization (i.e., quantitative restraint) which will bring the monetary base more into line with the longer term in GDP.

On fiscal policy, the government faces two challenges with short and longer term horizons.

One, if the economy is in a recession in 2023, the government will need to bring forward timely and targeted measures to protect the vulnerable and the economic capacity of the country without increasing inflationary pressures. In the 2022 Fall Economic Statement, which anticipates an economic slowdown, there were measures to help lower income people (e.g., GST credit, worker income benefit) and students and renters. Expect more of the same. Recessions tend to hurt lower income people disproportionately.

Two, Budget 2023 should provide a policy vision to promote competitiveness, sustainability, inclusion and resilience. Canada needs an energy transition plan that can support growth and climate change objectives. Policy work is required to examine the adequacy of support to workers in periods of economic weakness. Announcements are pending from the government on its review of the Disaster Financial Assistance Program. Plans do not guarantee policy success, but plans beat no plans. No plan means no accountability.

Underlying most efforts to strengthen Canada’s policy agenda in a post-Covid world is the need for supporting public and private infrastructure. El-Erian highlights infrastructure as a critical component of growing the supply side of the economy.

In Budget 2022, the government committed to a national infrastructure needs assessment. Research by Janet Lane and Carlo Dade at the Canada West Foundation underscores the link between trade infrastructure investments and competitiveness. Work by Ali Khan, Mostafa Askari and Craig Lonneberg at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy highlights the need and opportunities to strengthen data, methodology and governance to promote success in infrastructure with lessons learned from our competitors.

Notwithstanding past commitments and research, the federal government has yet to release its plans for a national infrastructure needs assessment. We are losing ground on our competitors on infrastructure policy.

There is a policy Catch-22. Addressing spending pressures related to health care, national defence and energy transition without additional revenues is likely not possible.

The Liberal 2021 platform and Budget 2022 made commitments to policy and operational reviews. The federal government has not had a spending review since the Deficit Reduction Action Plan launched by Prime Minister Harper and the late Finance Minister Jim Flaherty in Budget 2011.

The Fall Economic Statement laid out a prudent medium term fiscal framework that reduces the deficit and debt as a percentage of GDP. Holding the government to account on the fiscal plan will be a challenge.

There is a policy Catch-22. Addressing spending pressures related to health care, national defence and energy transition without additional revenues is likely not possible. On the one hand, it’s not easy for governments to talk about raising taxes in the lead up to the next election. On the other hand, deficit financing these pressures would result in a federal government that is not fiscally sustainable over the long term and likely a bond rating downgrade. Moving forward in Budget 2023 with a spending review process would appear to be a politically expedient and prudent policy step.

Bottomline, Canada has work to do to better position itself for the policy challenges of the post-COVID economy.

In 2020, the primary challenge for policymakers was to protect people and economic capacity. This policy mission was accomplished. There should be no regrets even if the large fiscal supports led to some excess demand relative to Covid constrained supply that boosted inflation.

In 2023, the primary challenge is to restore macroeconomic stability (i.e., inflation control) and set a policy course on energy transition that will strengthen competitiveness, sustainability, inclusion and resilience. Canada cannot afford to be policy complacent. We do not want to look back five to 10 years from now and realize that we failed to address inflation and make progress on critical policy challenges facing the 21st century. Similarly, we want to use limited fiscal capacity in a way that increases options for future generations to address global shocks.

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a contributing writer for Policy Magazine.

Azfar Ali Khan is the Director of Performance of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa.

Matthew Mcgoey is an undergraduate economics student at the University of Ottawa.