A Cautionary Tale on the Perils of Asking Too Many Questions?

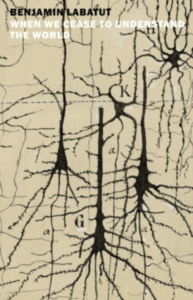

When We Cease to Understand the World

By Benjamin Labatut

New York Review Books/PRH Canada/September 2021

Reviewed by John Delacourt

January 8, 2022

A word about book recommendation lists, mainly because it is germane to the book reviewed. As we all emerge from our virtual bunkers and our new tradition of holiday season doomscrolling, it is likely that you, reader, scanned quite a few of these. The Guardian, the New York Times, what’s left of the book review sections in Canadian newspapers … their editors all know that such listicles make for good clickbait. There is an added feature, at least a decade old now, of having political leaders or CEOs post lists of their favourite reads as well.

With the latter, I’d venture they’re the least reliable guides, especially over the past few months. Requests for recommendations seem to be treated as public relations exercises, and more often than not delegated accordingly. Which makes sense. What political or corporate leader has had time to read widely or deeply in crisis mode? Or more to the point, who would risk admitting they’ve been curled up in a ball reading Scrubs on Skates and weeping over the last few weeks?

However, there might be one notable exception: the annual list of recommendations from a real writer and reader, Barack Obama. Obama’s well-received early memoir, Dreams from My Father, singled him out as a writer first and politician second, and some of Obama’s most memorable speeches (which I’d argue are the best of this century) bear the mark of at least one prodigiously talented author attentive to the music of great prose and the craft involved in creating a compelling narrative.

Which – finally – brings me to this year’s list from Obama, and a selection from left field: the third novel of a relatively obscure Chilean author, published with an imprint that mostly focuses on re-releases and new translations, New York Review Books. It is Benjamin Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World.

The book — weighing in at a light 192 pages and which Labatut chafes at labelling a novel, fusing as it does fact and fiction, preferring to call it “a work of fiction based on real events” — is not, on its face, a difficult read, despite the promise of its (English) title or what the copy on the back will tell you it’s about: “The complex ties between scientific and mathematical understanding and personal and historic catastrophe.” The characters bear a more-than-passing resemblance to their real life namesakes: Albert Einstein, Erwin Schrödinger, the computing and cryptography genius Alan Turing, the chemist Fritz Haber – along with a few lesser known but equally central figures in the advancement of sciences and mathematics over the last hundred years, including Alexander Grothendieck and Shinichi Mochizuki.

With such imposing subject matter, he has managed to craft a surprisingly moving, idiosyncratic history of the scientific achievements that have defined our understanding of the world.

But in a sly and sinuous way, as Labatut tells the story of how these great minds started to intuit radically different theoretical conceptions about the very nature of reality itself, the larger context emerges. All of these achievements were accomplished in the shadow of two world wars and destruction at an unprecedented scale. And fiction starts to bleed through fact as Labatut animates the inner demons that his characters contend with, and a kind of grail quest is defined: the grand unified theory that explains how natural forces operate at a subatomic level. The individual biographical sketches slowly become like charged electrons through Labatut’s tangents of thematic connection and counterpoint. And the effect is less a thesis than a meditation on the psychic costs of such heroic, visionary efforts to grapple with the ultimate mysteries of the physical world.

Labatut’s writing has been favourably compared to the late W.G. Sebald’s brand of fiction, which transcends distinctions between the factual and the invented and mines the seams of a kind of secret history of the last century. It has also aroused critics who link it to the broader, destructive propensities of “fake news” and political propaganda that consciously obviate truth to make reality seem subjective and malleable for tactical purposes. “In the current American political climate, even scientific fact—the very material with which Labatut spins his web—is subject to grossly counter-rational denial,” writes Ruth Franklin in her New Yorker review. “Is it responsible for a fiction writer, or a writer of history, to pay so little attention to the line between the two?”

Yet I’d say When We Cease to Understand the World bears closest resemblance to a work of non-fiction from the novelist Arthur Koestler, The Sleepwalkers. The author of the Cold War classic Darkness at Noon sought, with this lesser known work, to draw a through-line from a series of scientific revolutions by focusing on such figures as Galileo, Kepler and Newton to grapple with a theme of faith versus reason. Yet what he accomplished – through his novelist’s engagement with their motivations and inspirations – were portraits that revealed how deeply creative such theoretical science actually is.

Labatut has accomplished a similar feat of imagination. With such imposing subject matter, he has managed to craft a surprisingly moving, idiosyncratic history of the scientific achievements that have defined our understanding of the world. I suspect Obama recognized what a great feat of storytelling Labatut has accomplished with this work – as hopefully more readers will now. At a time when we can seem defeated by the scale of the challenge science is faced with during this pandemic, When We Cease to Understand the World reminds us of the inexhaustible drive to solve these mysteries, notwithstanding the tragic personal costs such efforts can exact.

Policy Contributing Writer John Delacourt not only reads but writes fiction, including the novels Ocular Proof, Black Irises and Butterfly. He is Vice President and Group Leader of Hill + Knowlton public affairs practice in Ottawa.