Why the WGA Strike is So Much More Important Than it Looks

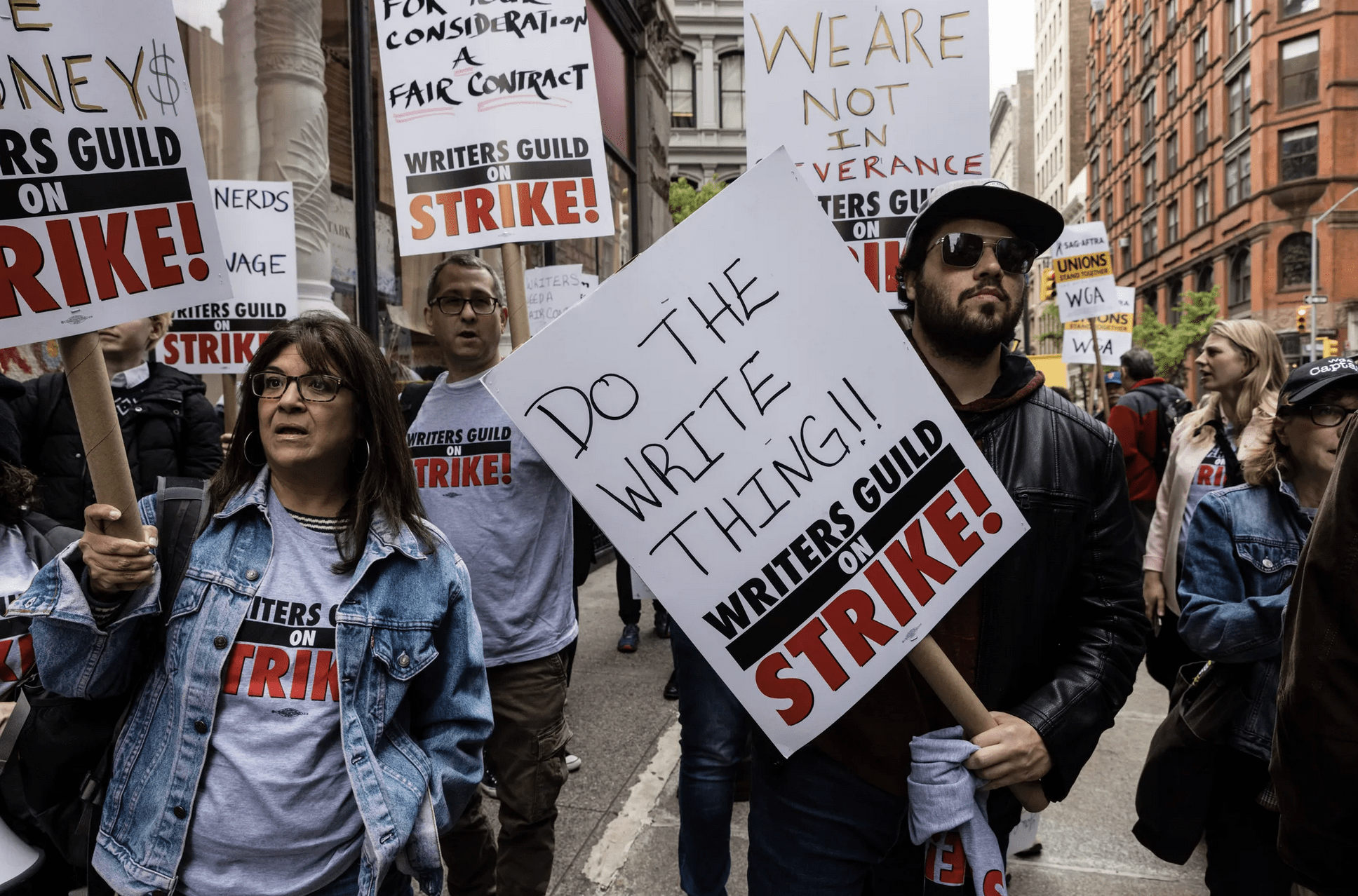

WGA members protest outside Netflix headquarters in New York on May 3, 2023/AP

WGA members protest outside Netflix headquarters in New York on May 3, 2023/AP

Lisa Van Dusen

June 15, 2023

Once, in a previous life, in a pre-pandemic, just barely pre-9/11 New York City, I was a member of the Writer’s Guild of America. More precisely, I was a member of the Writer’s Guild of America, East, or WGAE, which represents east-coast film, television, radio, news and online media writers.

In practical terms, my WGAE membership did not make my job writing international copy for Peter Jennings at ABC News any less hair-raising. But it was a privilege to carry the card of an organization with so much history, and so much more serious talent, in its DNA. In less practical terms, it gave me a pass to a series of pre-Oscar film screenings I was always either working too hard, or mothering too dervishly, to attend.

Today, the Writer’s Guild of America has taken on a whole new level of importance, not because it has changed but because its context has. The current strike by WGA members — East and West — puts striking writers in the position of fighting for not just their own livelihoods but for the livelihoods of human beings in other creative work, in other sectors and in other places around the world.

Artificial intelligence is a key issue in this strike, “displacing more familiar fears like the rise of streaming and the decline of residuals,” per Variety. “Writers on the picket lines fear that movie studios will use AI to write scripts – either in whole or in part – diminishing the role of writers or even making the job obsolete.” With the potential impacts of AI on multiple fields of human endeavour and economic viability only recently being widely discussed, that obsolescence anxiety puts WGA members at the forefront of an existential crisis. Countless workers — from Amazon warehouse employees to retail cashiers to computer coders to lawyers to a range of other jobs known and unknown — are experiencing now, or will be soon, the same concerns. That Hollywood writers are striking over AI makes this the highest-profile test so far of how society will respond to this moment.

The WGA’s position — the product of extensive research, including by members immersed in tech both current and futuristic because they write on sci-fi shows — is not to rule out the use of AI but to protect writers from economic harm. “In essence, writers are asking the studios for guardrails against being replaced by A.I., having their work used to train A.I. or being hired to punch up A.I.-generated scripts at a fraction of their former pay rates,” reports James Poniewozick in the New York Times.

We are living through a watershed moment in the evolution of human rights, from the ludicrous attacks on voting rights, reproductive rights and LGBTQ+ rights in America to attacks on journalists and freedom of speech around the world. The abuse of technological innovation as a means of borderless, unregulated power consolidation, propaganda dissemination, wrongful surveillance and hacking enabled by the internet since 2000 has coincided with a politically-fronted global war on the same democracy that protects humanity from the most Hobbesian implications of this moment. If you were to chart on a graph the rise of disruptive technology and the concurrent depletion of democracy over the past two decades — think, in alphabetical terms, of the unequal post-pandemic economic recovery translating to a K-shaped graph — it would be an X-shaped dystopian nightmare. Which makes this WGA strike anything but a routine labour story.

This strike, like previous strikes, is a dispute between the WGA and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, whose members now include the major motion picture studios (including Paramount Pictures, Sony Pictures, Universal Pictures, Walt Disney Studios and Warner Bros.), the principal broadcast television networks (including ABC, CBS, FOX and NBC), streaming services Netflix, Apple TV+ and Amazon, the cable networks, and other independent film and television production companies.

If you were to chart on a graph the rise of disruptive technology and the concurrent depletion of democracy over the past two decades, it would be an X-shaped dystopian nightmare. Which makes this WGA strike anything but a routine labour story.

But unlike in previous strikes, the bilateral leverage dynamic has changed. In the 15 years since the last strike, the AMPTP members have become significantly more powerful. In the same way that the internet has both precipitated and rationalized the disempowerment of journalism as a pillar of democracy, the fragmentation of content production and the glut of supply that have transformed the entertainment industry have shifted power from the talent to the producers. Just spend 10 minutes doomscrolling any Saturday night through the Automat of abasement — of both talent and audience — that some streaming services offer for evidence of that shift. This is what a cultural buyer’s market looks like in a revolutionary glut.

Meanwhile, as politics have been besieged by the operational chaos of the post-Obama era, accountability, integrity, honesty, character, public service, community and civic responsibility have been actively marginalized by the sort of soul-sucking diversion dramaturgy that gives 21st-century narrative warfare such a bad name. Joe Biden is president of the United States but Donald Trump is, apparently, still president for life of cable news.

Which means that the moral imperative that would have once compelled the interests on one side of this bargaining table to avoid treating workers atrociously is also skewed by context. The critical mass of pressure being exerted on individuals in positions of all sorts of power — from politicians to supreme court justices to corporate CEOs to multilateral organization heads to tech titans — to lower human rights standards in democracies to those of aspiring-new world order autocracies is such that any narrative whose outcome can deliver a blow to those rights automatically becomes a less-than-zero-sum game.

For this strike, at this juncture, that means its consequence as a norm-breaking, precedent-setting showdown between what Eurasia Group President Ian Bremmer calls the “digital global order” — represented by tech companies, streaming companies and AI companies (overlap included), though he forgot to include rogue intelligence interests — on the one hand and human beings seeking to protect their rights, their economic power and their intrinsic value on the other is enormous. With the whole world watching, the content producers have a choice to make that’s about much more than money.

So, the role of AI in this story makes the WGA strike at once historic and underestimated in that status. AI is not the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. It is not the Stonewall riots. It is neither Selma nor Kent State. The threat to human rights based on AI’s impacts on profits and privacy hasn’t arrived in one galvanizing, action-mobilizing flashpoint; it’s more incremental and insidious. But history may look back on this strike as a similar turning point.

In a frequently quoted scene from a movie that has held up so well as both a tribute to, and caution against, the crossover between journalism and entertainment, Albert Brooks as Aaron Altman in Broadcast News warns that the devil, should he appear, won’t have a long, red pointy tail. “He’ll just, bit by little bit, lower our standards where they’re important.”

A sentence written by human being, comedic genius and WGA member James L. Brooks, who spent last Friday on the picket line.

Policy Magazine Associate Editor and Deputy Publisher Lisa Van Dusen was a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.