Will the Highway to Climate Hell Run Through Sharm el-Sheikh?

Amid a gathering confluence of hope, skepticism and taxi surveillance at the Sharm COP27, former Canadian Green Party Leader Elizabeth May — uncharacteristically watching this COP from home as she campaigns for co-leader of the party she headed for 13 years — flags the possible sources of COP disaster.

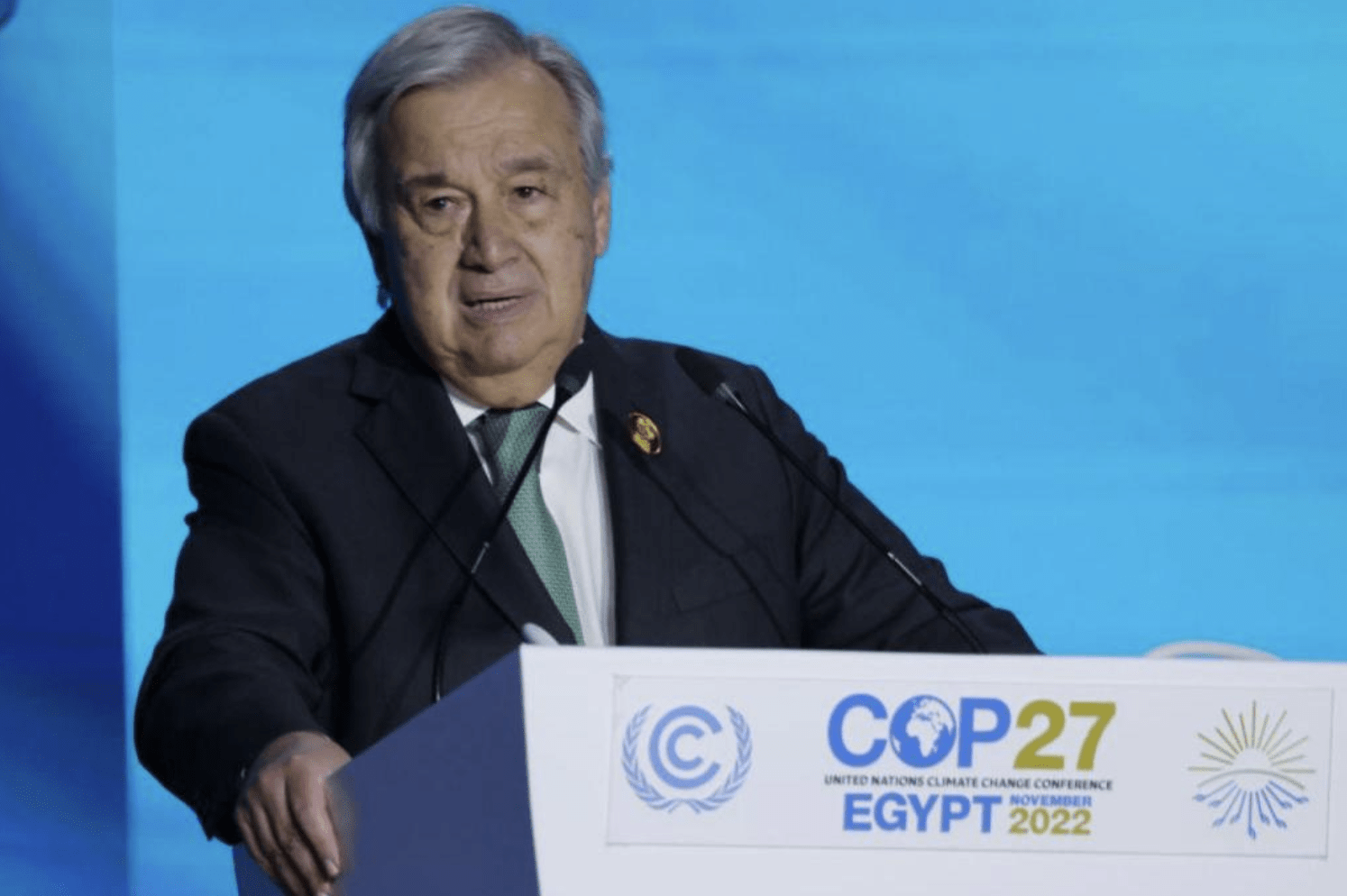

‘We are on a highway to climate hell’: United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres at COP27, Nov 7, 2022/CNN

‘We are on a highway to climate hell’: United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres at COP27, Nov 7, 2022/CNN

Elizabeth May

November 7, 2022

Sharm el-Sheikh — the Egyptian beach resort shorthanded as “Sharm” hosting this year’s United Nations climate change conference — is known as a Red Sea tourist magnet for its stunning scenery, conference facilities and nightlife. It remains to be seen whether it will take its place on the catastrophe or success side in the catalogue of COP datelines.

Climate Conferences of the Parties (COPs) move around the map according to a roster set by the United Nations. The negotiations, held every year unless otherwise determined by the parties, rotate datelines among the five recognized UN regions — Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Central and Eastern Europe and Western Europe — from industrialized countries, to developing nations, to economies that were once part of the USSR, and so on. This year, COP27, is Egypt’s turn.

It is generally the case that healthy democracies make the best host countries for these conferences. Having attended 13 COPs going back to 2005, I can attest to the synergistic dynamic between the mobilization of people in the streets outside the venue and pressure on the delegates to produce results — a dynamic very much evident last year at COP26 in Glasgow. That has not always been the case.

The Copenhagen negotiations in 2009 were disastrous — both a logistical nightmare and policy failure. Hundreds of protesters were arrested by Danish security forces who also harassed and menaced country delegates. Through the host country’s mismanagement, multilateralism in search of an agreement to replace Kyoto was nearly derailed for good.

The following year’s COP in Cancún pulled the process back from the brink, but it was not until 2015 and COP21 in Paris that an agreement was reached. And even in Paris, that usual dynamic of healthy protests driving progress was absent due to the devastating impact of the terrorist attacks two weeks before the COP opened that killed 130, including 90 people at the Bataclan theatre.

Amid the post-Arab Spring regression of Egypt’s government to not only Mubarak-era police state tactics but the more sophisticated suppression tools of modern surveillance states. These include, per Human Rights Watch, “the installation of cameras in all 800 taxis,” in Sharm, “allowing security agency surveillance of drivers and passengers,” from a “security observatory” run by Egypt’s notorious Interior Ministry. Egyptian security forces have been arbitrarily detaining activists ahead of COP27. Amnesty International warned on Sunday that “World leaders arriving in Sharm El-Sheikh for COP27 must not be fooled by Egypt’s PR campaign. Away from the dazzling resort hotels thousands of individuals including human rights defenders, journalists, peaceful protesters and members of the political opposition continue to be detained unjustly. They must urge President Abdelfattah al-Sisi to release all those arbitrarily held for exercising their human rights.”

Meanwhile, scientists are warning that time may have run out on the Paris Agreement’s call to hold global average temperature to no more than 1.5 degrees C. The world is currently on track to nearly twice that. And the impacts of exceeding 1.5 degrees appear to have been underestimated, as demonstrated in a study published in September in the prestigious journal Science:

“We show that even the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to well below 2°C and preferably 1.5°C is not safe as 1.5°C and above risks crossing multiple tipping points,” the authors write. We must pay close attention to the costs of exceeding these tipping points, or climate conditions beyond which change becomes self-perpetuating and self-accelerating.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, who seems to be running out of ways in which to express his alarm at the lack of cooperation on climate change, was blunt in his opening message to leaders and negotiators gathered at Sharm on Monday.

“Greenhouse gas emissions keep growing. Global temperatures keep rising. And our planet is fast approaching tipping points that will make climate chaos irreversible,” Guterres said. “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator.”

It is generally the case that healthy democracies make the best host countries for these conferences. Having attended 13 COPs going back to 2005, I can attest to the synergistic dynamic between the mobilization of people in the streets outside the venue and pressure on the delegates to produce results.

A key part of COP27’s agenda about which we will hear far more before the conference wraps on November 18th is “loss and damage.” It was at COP19 in Warsaw in 2013 that the concept of “loss and damage” was added to the long list of recurring items in United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations. It boils down to basic justice and it has been, so far, intractable. The burning of fossil fuels in industrialized countries has led to climate impacts that cause immense damage in those countries that have contributed the least to the problem. Developing countries want the rich to pay. Countries including the United States and Canada reject the notion.

Back in 2013, just as COP19 opened, a devastating typhoon hit the Philippines. Typhoon Haiyan was killing people and wiping out villages as we gathered in Poland. The lead Philippine negotiator, Yeb Sano, shared his efforts to reach his own family. He did not know whether they had survived. He began a hunger strike which continued through the conference with many, including me, joining him in solidarity.

By the close of COP19, the concept of loss and damage was codified as the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage Associated with Climate Change Impacts (Loss and Damage Mechanism) but no one knew whether the principle could succeed. By the Paris Agreement in 2015 loss and damage was included in Article 8 with the vaguest of non-commitments: “The Warsaw International Mechanism shall collaborate with existing bodies and expert groups under the Agreement, as well as relevant organizations and expert bodies outside the Agreement.”

As 1.5 degrees slips out of reach, and galloping climate disasters hit country after country, the Egyptian presidency of COP has made achieving progress on loss and damage COP27’s key goal.

Focusing on the loss and damage debate at the expense of broader action to avoid slipping past .5 to 1.6, or even past 2 or 3 degrees is a dangerous error, no matter how valid is the developing world’s case. We can do both — meet the demands of the world’s poorest nations for loss and damage progress, and must move away from fossil fuels and restore massive areas of forest far more quickly than the wealthy nations of the world have been prepared to do.

Over 120 world leaders plan to attend COP27, including US President Joe Biden and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Canada’s prime minister will not be attending, heading to Cambodia for the ASEAN summit, the Bali G20 and the Francophone Summit in Tunisia instead. This is deeply disappointing. While the Canadian delegation will be headed by Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault, individual countries’ commitments are measured by the presence of their heads of government at COPs.

We have been ignoring the warnings of science for so long. Now we have our own stories of loss and damage: We have the 700 people who died in four days last year in British Columbia’s heat dome; the Village of Lytton that burned down in minutes in those same days; the 2021 fall atmospheric rivers that caused billions of dollars in lost infrastructure in BC; and this fall’s Hurricane Fiona with the havoc and grief still fresh. The whole world is rocked almost daily by extreme weather events driven by rising greenhouse gases and loss of carbon sinks.

COP27 is also meeting in the shadow of increased global geopolitical instability, including the energy disruptions produced by Vladimir Putin’s illegal and immoral war on Ukraine. Climate events and that war have contributed to rising costs of living that have their own feedback loops. Just as warming gases release more warming through positive feedback loops, political instability and inflation, worsened by climate change, threaten to unleash political backlash that could rationalize an otherwise unthinkable victory for a transformed, anti-democracy Republican Party in the US midterms on Tuesday; a party determined to undo President Biden’s efforts to arrest the worst of the climate emergency.

We are in a race against time to hang on to functional democracies capable of addressing these threats, just as we are in a race against time to act to arrest climate breakdown.

These are unenviable times for political leaders aware of the risks. Political courage is needed, and Canada is elsewhere.

Contributing Writer Elizabeth May, MP for Saanich-Gulf Islands, has been a leading Canadian green activist since the landmark Rio Summit of 1992.